Quantum Christians and Other Surprises

By Neil Earle

While laying no claim to being a scientist I have seen the need to at least keep up with the “gossip” in scientific circles over the years.

And even that is hard to do these days. Thankfully, the January/February 2020 Discover magazine followed its tradition of updating the year in science, as far as the big trends are concerned. So much goes on in the world of scientific/technological breakthroughs that is easy to miss. Discover reports on the problems Israel and India had landing research craft on the moon’s surface while China was scouting the dark side. In 2019 astronomers at eight sites around the world photographed a black hole for the first time and a 3.8 million year old human ancestor fossil tuned up in Ethiopia.

From the rocks to the stars, scientists are still at work persevering through setbacks and advances to dig out the secrets of the cosmos, exactly as the Bible encourages (Proverbs 25:2).

Two of Discover’s 50 updates – a nice bargain for $6.99 – had to do with the ever-intriguing world of Quantum research.

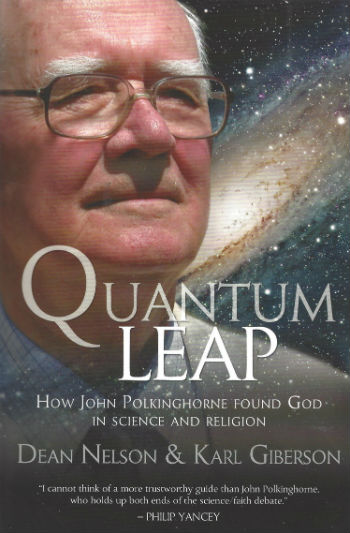

Now there’s something worth pausing over. The Both/And or Yes/No implications of Quantum physics has always intrigued many Christian researchers, most notably Sir John Polkinghorne, British perfecter of quark theory. Polkinghorne surprised colleagues some years back by switching from a career in physics to the Anglican priesthood.

What was going on?

John Polkinghorne

John PolkinghorneThe Tao of Science

According to Polkinghorne biographers Dean Nelson and Karl Giberson, it was at Cambridge while working on cutting-edge particle physics that Sir John became convinced that “science was often not as objective as it appeared to be.” Rather, scientific discovery was deeply personal and rooted in the motivations of the scientists themselves. Polkinghorne found support in the conclusions of Michael Polanyi’s critique of science as being only concerned with facts: “Compete objectivity, as usually attributed to the exact sciences, is a delusion and is in fact a false idea,” Polanyi concluded.

The example of Columbus hits home. Columbus was guided by personal conviction that if he sailed west he would reach the Orient. He was wrong, but he was right in believing it was possible to reach one part of the world from the other. His revolutionary voyages showed irrevocably that the world was round. That was a massive discovery even if resting on inaccurate maps and a false premise.

Likewise the wave/particle duality in the discoveries about Light some years back. Now we know it is somehow both. For Polkinghorne this teaches us that “reality is surprising” and that “science is only one slice of reality.”

Quantum Weirdness

“Quantum weirdness” is the way Discover magazine introduced the evidence advanced by IBM’s Latke Minev. By watching a quantum jump in slow motion Minev moved beyond the anomaly introduced by Niels Bohr of unexpected quantum leaps – particles jumping from one orbit to another. Quantum particles not only move in continuous transition but send out subtle signals before they leap. Jumps could even be reversed. The payoff is that manipulating quantum states in this way sets up new procedures for error-correction in the eargerly anticipated quantum computers.

In the same issue an article by Stephen Ornes shows how Google’s Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab (!) documented the possibility of exponential growth in quantum computer chips – completing programs in 200 seconds that would have required 10,000 years on a supercomputer!

Astounding! “A few quantum computers already exist,” says California technologist Roger Lippross, “but are so very hard to build. They’re not ready yet to go on the market but think of the impact when they finally do.”

There are still “bugs” to work out of course, in true scientific fashion, but physicists Jonathan Dowling and Hartmut Neven are already toying with things that they had expected to appear 50-80 years into the future.

A Most Surprising Cosmos

Quantum mechanics has been the hottest subject in science these past 10-15 years and things look like they are about to take off. Polanyi’s thesis that scientific breakthroughs build on one another once researchers are “open to surprise” appears vindicated.

We live in a new Golden Age of scienctific discovery.

We live in a new Golden Age of scienctific discovery.The pastor-physicist John Polkinghorne draws out the spiritual implications. “God has given creation the gift of being itself.” Built into the dynamic powers of the created order is what theologians have labeled for millennia as “contingency” – the freedom of the cosmos to develop along lines that surprise even the Einsteins and Bohrs. It is, in Polkinghorne's religious worldview, a creation that includes both cancer cells and sacrificing red blood cells – saints and sinners, concentration camps and Mother Theresa’s with human free will and the imperative to choose left unimpaired. Sir Frederick Banting invents insulin and dies in a plane crash while crooks and rogues often go undetected, let alone punished.

To some, quantum theory points to the paradox of existence, a paradox resolved for Christians such as Polkinghorne in what early Christians called “the cosmic Christ,” the One who holds all things together (Colossians 1:17) and who called the created order into being out of nothing except the word of his power (Hebrews 11:3). Some will scoff at Polkinghorne's conclusion but he is a visionary who believes “no real conflicts exists between science and Christians, though there are unasnwered questions about how they relate.” He crosses the boundary between scientific philosophy and theology. The long-assumed Western infatuation with pure logic falls before quantum physicists accustomed to counter-intuitive thinking. “Even logic has to be modified when it is applied to the quantum world.”

In an era when we now know that only 4% of the known universe is observable, Job’s question haunts us all: “Where shall wisdom be found and where is the place of understanding?” As we continue into the 21st century the answer seems to be still ahead of us and beckoning us on in the spirit of true scientific and even religious enquiry.