Why Einstein Matters

By Neil Earle

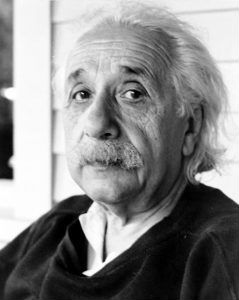

Albert Einstein

Albert EinsteinEvery month or year has its important anniversaries. Here’s one worth noticing. “The modern world began on 29 May 1919 when photographs of a solar eclipse, taken on the island of Principe off West Africa and at Sobral in Brazil, confirmed the truth of a new theory of the universe.”

Thus is historian Paul Johnson’s opening for Modern Times. The “new theory of the universe” had been set forth by a former Swiss patent clerk named Albert Einstein.

Catching those Gravitational Waves

Einstein is still a name to conjure with. Take gravitational waves, for example. The January/February 2018 Discover magazine listed this as Number Three on its Top 100 recent discoveries of science. “In 2016 LIGO (short for Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) announced it had detected gravitational waves for the first time, confirming Albert Einstein’s predictions in general relativity.”

Einstein’s great friend John Wheeler – exponent of the Black Hole discovery – wrote in 1998 that relativity theory had insinuated how “space-time” can wiggle and vibrate emitting energy as it goes. “General relativity predicts gravitational waves,” Wheeler stated hopefully in 1998, a statement now affirmed.

“What could cause a gravitational wave?” Wheeler speculated in his memoir, “Some gravity waves could still be bouncing around the universe today as a result of the violence of the Big Bang at the beginning of time. Supernovas exploding and matter collapsing into black holes inevitably produce such waves…Detecting them poses an enormous challenge.”

But now Discover quoted Ryan Foley of the University of California, Santa Cruz: “We’ve been waking around for all of humanity being able to see the universe but not being able to hear it. Now we get both.”

Score another win for Einstein. Now, back to May 29, 1919.

Thorne of Cal Tech is consulted re Time Dimensions in movies such as Interstellar.

Thorne of Cal Tech is consulted re Time Dimensions in movies such as Interstellar.Beyond Euclid

Einstein's ideas on General and Special Relativity (1905, 1915) had shown that the straight line geometry of Euclid and Galileo’s notions of time as an unmoveable absolute unit flowing forever in one direction – the assumption behind Newton’s “clockwork universe" approach to physics – could not explain how Gravity seemed to bend and affect light. Huge bodies such as the sun's gravitational field, he specualted, should actually deflect light by 1.74 seconds of arc. Einstein waited for field evidence to confirm his theory.

On May 29, 1919 a British team verified Einstein's ideas by observing and photographing an eight minute eclipse. Then in 1923 Edwin Hubble confirmed by the red shift observed from the Mount Wilson observatory in California that the galaxies are receding from us. This gave credence that the new “expanding universe” called for a higher physics than a world of parallel lines plotted on measureable graphs. Euclidean geometry could measure the small distances from Cairo to Alexandria but had to be replaced by something more sophisticated when dealing with an unfolding universe moving at great speed.

Einstein greatly benefited from the work of others. By the late 1800s many physicists had seen the problem trying to apply straight-line geometry to a solar sytem in motion where circular planets orbited the sun in an ellipse rather than perfect circles. Some planets were found rotating irregularly. In 1676 Light had been clocked at 186,000 miles per second and in 1865 James Clerk Maxwell had proposed Light was an electromagnetic wave. The existence of electromagnetic fields meant the universe was more complicated than Newton and his predecessors had envisioned. The new vision was a “a meshwork of interacting fields.”

Mathematics had shown what every airplane traveler knows – straight lines are not always the shortest distances. If Light could be bent and curved and Light was the constant time measurement in the universe then Time itself could be affected – able to be slowed down as we experience in the “time delays” built into our hand-held devices. Tenerife confirmed this and Einstein became famous. Biographer Ronald Clark shows how Einstein supposedly taught his son the Parable of the Blind Beetle. “When the Bind Beetle crawls over the surface of a globe, he doesn’t notice that the track he has covered is curved. I was lucky enough to have spotted it.”

The new insights into Space and Time – now labelled Space-Time – was humorously summarized in a dinner given in Pasadena to honor the very Professor Eddington who had led the Principe expedition. The limericks feature a comic debate between Eddington and Einstein:

You hold that time is badly warped.

That even light is bent;

I think I get the idea there,

If this is what you meant:

The mail the postman brings today

Tomorrow will be sent.

The shortest line Einstein replied,

Is not the one that’s straight;

It curves around upon itself

Much like a figure eight,

And if you go too rapidly

You will arrive too late.”

Thinking God’s Thoughts

By the 1920s Einstein was a celebrity and had been quizzed about his beliefs in God and religion. A Catholic cardinal had attacked Relativity as a cloak for atheism, more cold, austere calculations such as E=MC squared seemingly leaving God out of the creation. Einstein insisted that he saw divinity in the smooth harmony of creation. He often talked about God (‘the Old One”) in an offhand way, as in “trying to think God’s thoughts after him.” He was not a practicing Jew but he certainly possessed a mystical streak, showing up for chapel at Princeton during World War II and playing Mozart on his violin in honor of Jews he knew trapped in the Holocaust.

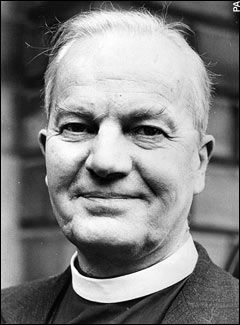

Edinburgh theologian Tom Torrance

Edinburgh theologian Tom TorranceThese tendencies have made him interesting for Christian thinkers.

The Edinburgh theologian Tom Torrance saw that Einstein and his generation had punched holes in the neat three-dimensional and somewhat cramped world of 1700s science – the boxed in or container model of the universe. The expanding cosmos was much more complicated and continuously throwing up new realities. It featured dynamic interactions between Light and Time and Energy and Matter that allowed for new possibilities. Torrance admired the way Einstein and his companions in the New Physics (1890-1930) were sketching out a revolutionary new approach to the cosmos. Straight lines were still there and Pythagoras’ theorem held true over limited surfaces but now everyone knew there were bigger realities “out there.”

New theories were needed to encompass new realities. Similarly Torrance encouraged Christians to study all over again “the strange new world inside the Bible.” Biblical witness to virgin births and resurrections had been ruled out by skeptical philosophers of the 1700s as violations of a law-based “Newtonian” system inside a limited “container” universe. Torrance argued that the newly surprising cosmos of the New Physics even made it possible to theorize about God Himself entering our reality to “become flesh and dwell among us.”

Holding it All Together

Torrance and others had respected St. Paul’s teaching that not only was Christ the Ruler of creation but that in Christ the whole system held together (Colossians 1:16-17). A supreme intelligence had made a cosmos not a chaos (Isaiah 45:18) and yet this universe could not explain itself and was running down – not able to sustain itself indefinitely. The New Testament had clearly shown Jesus as Redeemer and Sustainer. “He upholds the universe by the word of his power” (Hebrews 1:3).

Interstellar touched on issues relating to Time dilation in the farther reaches.

Interstellar touched on issues relating to Time dilation in the farther reaches.Theologian Murray Rae explains the implication here. Christianity is a claim about the way Reality is constructed as well as a way to live. Jesus was infinitely more than a guru or an intellectual sage. His becoming the Second Adam, the forerunner of a new creation, says Norman Wirzba of Duke Divinity School, means Jesus is the ultimate “Yes” to God’s commitment to keep the bewildering complexities of creation on trajectory. Eventually God himself is scheduled to reside in a transformed new creation, a New Heaven and a New Earth (Rev. 21) – a theme the Bible had propounded for centuries. The Greeks had speculated and science supports that there is a profound underlying order, a Supreme Logic (from Logos – see John 1), behind the manifold workings of creation.

Order permeates the process, says theologian Murray Rae, because the Logos himself has started it, entered it and promises to fulfill its reason for being (Romans 8:20-21). Indeed the concept of underlying order and purpose is the irreplaceable Christian contribution to the rise of the entire scientific method.

There was a certain irony in all this. NASA’s Robert Jastrow had quipped that scientists spent centuries climbing the mountain of ignorance only to see a group of theologians waiting at the top. Possibly. For we now discern that there is still much to learn about our developing cosmos – a dynamic system carrying out the Genesis command to be fruitful and multiply and to throw up startling new realities such as dark matter and wormholes, the new vocabulary of our times. In the midst of it all the New Testament offers the ultimate reassurance: “He upholds the universe by the word of His power” (Henrews 1:3).

Einstein seemed to intuitively grasp this, which is another reason he still matters.

For Further Reading:

Ronald W. Clark, Einstein: The Life and Times (New York: Avon Books, 1971)

Dennis Danielson (ed.), the book of the cosmos: Imagining the Universe from Heraclitus to Hawking (New York: Perseus Books, 2000)

Kip Thorne, Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein’s Outrageous Legacy (New York: Norton, 1994)

A.B. Torrance and Thomas McCall, Christ and the Created Order: Perspectives from Theology, Philosophy and Science (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018)

Thomas Torrance, Space, Time and Resurrection (Edinburgh: T and T Clark, 1998)

John Wheeler and Kenneth Ford, Geons, Black Holes and Quantum Foam: A Life in Physics (New York: Norton, 1998)