Science and Religion – Shifting Parameters?

By Neil Earle

NOVAS TOUCHING? There are wonders in the heavens far beyond what we can see in the night sky.

NOVAS TOUCHING? There are wonders in the heavens far beyond what we can see in the night sky.

As a minister, a teacher and a historian I can’t avoid this question. My church audiences often exhibit nervousness over the latest hominid skeleton dug up in Kenya or the discovery of new galaxies perhaps capable by inference of supporting “some form of life.” These breakthroughs will – some fear – undermine the authenticity of the Scriptures and subvert faith in God.

Then, on the other hand, as a historian, trained in analyzing arguments, many of the ideas I read in support of the 6000-year old earth, dinosaurs before the Noachian Flood, or “day-age” theories of Genesis One – some of these claims have a suspicious ring to them. They smack of special pleading, stretching evidence way out of context and, worse still, reflecting fear and defensiveness. And fear is not faith.

So where do we go to find common ground?

After the Monkey Trial

Until O.J. Simpson came along, the most famous court case in American history was the Scopes “Monkey” trial of 1925. In Dayton, Tennessee, a substitute biology teacher named John T. Scopes was accused of introducing evolution into his classroom. This was technically illegal in 1920s Tennessee though the state-approved textbooks included evolutionary material. Our article in this series, “Scopes Restaged,” touches on this issue. Though Scopes lost the case, many felt that his lawyer, Clarence Darrow, won the country by refuting some cherished beliefs of prominent Christians, beliefs which made the Bible seem weak and out of date. But were these beliefs biblical?

Today the Science-Religion debate rages as fiercely as ever. Nobel Prize-winning physicist Steven L. Weinberg sharpened the issue in the April, 1999 edition of The Chronicle of Higher Education. “I think that we should be very careful not to give the impression to the public that somehow our scientific work is converging with religion into a synthesis.”

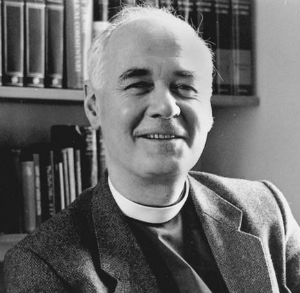

John Polkinghorne

John PolkinghorneHe added: “I don’t want a constructive dialogue. I don’t want to reconcile science and religion. I think it’s very good that they remain at odds with one another.”

Let’s thank Dr. Weinberg for his honesty, at least. Religion, for him was and is a destructive force. Many agree with him.

Shifting Assumptions

Yet on the other side, science is not the infallible towering juggernaut it once seemed. Science, said Carl Sagan, is a double-edged sword. Think of Chernobyl. Evolutionary science, especially, has been taking some big hits lately. Gary Zacharias’ article “Ten Tough Questions for Evolutionists,” touches on this. And Chuck Swindoll’s humorous “The Evolution of Cars” dares poke some fun at the conflict.

And the focus of the debate has shifted quite a bit since 1925, in spite of Dr. Weinberg’s reactions. A former colleague of mine, John Halford, a minister deeply interested in this issue, interviewed some of the big names on both sides and concluded: “Today, there are physicists who sound like theologians…and theologians who sound like physicists.” John C. Polkinghorne, retired president of Queen’s College at Oxford, is one of them. Dr. Polkinghorne argues the fact that the part of the universe we in habit seems so very hospitable to life it can’t be an accident.

Lately, astronaut Jim Lovell made the same claim.

Common ground? After all the ink that has been spilled and heated words shouted into the air?

William Jennings Bryan – being appreciated for his worries about science without morality. (Wikipedia)

William Jennings Bryan – being appreciated for his worries about science without morality. (Wikipedia)Religion vs. Reductionism

In the same journal which offered Weinberg’s candid remarks, theologian Anna Case-Winters, took the opposite tack. While fully admitting that “theology has some catching up to do,” Case-Winters re-presented what William Jennings Bryan worried about at the Scopes trial in 1925. It was missing at the Monkey Trial and it is often missing today. It is this: Religion – and biblically-based religion in particular – has irreplacable value as a shield against “reductionism,” the propensity to view all that happens in nature as mere mechanistic behavior, the amoral playing out of physical processes.

Sex education in many quarters has developed as a mere exercise in anatomical parts. Is that all there is? Bible writers thought. “And God saw all that he had made, and it was very good…The man and his wife were both naked, and they felt no shame” (Genesis 1: 31; 2:25). God is not a prude and the Song the Bible calls the Song of Songs is so explicit in parts it was censored in some places in Christian history.

The truth is that a religious perspective on this diverse and multifaceted creation could reignite that child-like sense of wonder which pervades the Bible’s nature poetry – a holistic approach that Albert Einstein and other scientific pioneers saw as essential for successul scientific investigation. This attitude not only guards against environmental degredation – a concern shared by many dedicated scientists – it might also form the foundations of a responsible “value added” scientific worldview.

Humpback whale breaching. (Wikipedia)

Humpback whale breaching. (Wikipedia)The biblical writers view creation as both beautiful and efficient. “The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands” (Psalm 19:1).

Our Cyclops-like media often misses this. Though subject to deterioration or decay (Romans 8:20), unformed and shapeless as are some of creation’s constituent parts, Biblical authors saw enough symmetry and predictability in Nature to shout forth the existence of a supreme, all-powerful, personal Creator: “How many are your works, O Lord! In wisdom you made them all; the earth is full of your creatures. There is the sea, vast and spacious, teeming with creatures beyond number – living things both large and small” (Psalm 104:24-25).

Noone who has seen a whale breaching will forget it and God used these allies of his to hunble both Job and Jonah. Jesus advised his followers – consider the birds, look at the flowers of the field, don’t you know sparrows have God’s attention.

Awe and Wonder

The biblical view is that creation is the stage set for the drama of salvation. And what a set it is! From this perspective, Science and Religion are more complementary than is usually thought. Halford and Polkinghorne were ahead of the curve on this. Science excels at “what” – Religion probes “why.” Professor Nancey Murphy at Fuller al Seminary, is also a passionate scientist. She argues: “Theology and science should not be kept in watertight compartments.”

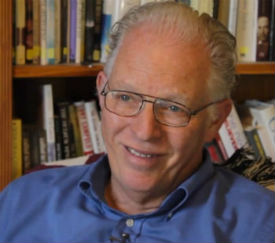

John Halford

John HalfordTo believers in the Bible, this creation, the Cosmos that scientists love to explore and explain, has worth and dignity conferred upon it as the field of God’s activity of salvation, as having his special cocnern lavished upon it. Canada geese in flight, platypus ducks and their impossible anatomy, the miracle of the human eye that even Darwin worried about as fatal to his theory – in all this the physical creation testifies. A Biblical sense of awe and wonder could guard against a mechanistic obsession with cold data and pettifogging details. One would think after all these centuries that Genesis 1 would be recognized as a revolutionary study in both gender equality and genetics: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27).

Created in the image of deity? Women as well? Scientists, too? Wow! That would change things if it were fully digested! Christians know this: With apologies to Star Trek I, the Movie, we are more than conveniently designed “carbon units” occupying space and time. The biblical teaching is healthy and holistic. At times it soars: “From one man he made every nation of men, that they should inhabit the whole earth…God did this so that men would seek him and perhaps reach out for him, though he is not far from each one of us. ‘For in him we live and move and have our being.’ As some of your own poets have said, ‘We are his offspring’” (Acts 17:26-28).

Matters of Meaning

Deep down inside we sense a purpose to things, something going on behind the curtain, a deep mystery to this Cosmos in which we float as specks of dust. The religious dimensions of awe and wonder offer a fresh and exhilirating way to view the data from science. Both sides need a fresh approach. Science needs to say to Religion – “Don’t feel so threatened. We really don’t have all the answers, you know.” Religion needs to respond: “Fine. But can you interpet your data more carefully, considering the collateral effects upon values and behavior?”

Such an approach is long overdue.