Thomas Torrance and the New Physics: Theology Meets Science in a Fresh Convergence

By Neil Earle

Tom Torrance

Tom Torrance“The cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be,” eloquently intoned astronomer Carl Sagan in his massively successful television series “Cosmos.” His almost reverent declaration of atheism was made in 1980. On April 30, 2012 cosmologist Lawrence Kraus, author of A Universe from Nothing, was quoted under the headline “A Universe without Purpose.” Purposelessness, as Kraus reported, “is far more satisfying for me than living in a fairy-tale universe invented to justify our existence” (LA Times).

Fairy-tale universe?

Who is Kraus scoffing at? At least Sagan possessed a love for the creation.

But is there a word from the Lord about all the recent flurry of attention given to meaninglessness as a clue to this silent universe whose measureless dimensions overwhelm us?

There is indeed. A leading Christian voice in the correlating of cosmology with Christian theology in our time was the Edinburgh theologian Thomas Torrance (1912-2007). In an impressive series of articles, books, and lectures Torrance proclaimed his assertion that the New Physics – those developments in the early 1900s spearheaded by illustrious figures Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Max Planck and Kurt Gödel – their approaches were “not uncongenial” to theology (Divine and Contingent Order, 70).

In fact, states Torrance, developments from 1900-1925 correlate quite well with aspects of early Christian thought. He meant, in particular, the creative penetrations into the nature of Reality necessitated by well-known terrain for theologians – the Trinitarian discussions of the 300s AD especially the deeper insights into the Incarnation provided there.

Trinity? Incarnation? Relevant in our ultra-scientific age?

How so?

Torrance's book lays out how modern physics gives us a better understanding of Jesus' resurrection.

Torrance's book lays out how modern physics gives us a better understanding of Jesus' resurrection.Intrusions into Nature?

For openers the Christian contention that the Creator God could become "the Crucified God," a theme which occupied his German contemporary Jurgen Moltmann as well, brought a gale of fresh air into a scientific worldview that had been burdened with a “boxed in” solely mathematical approach to the universe. Newton and others had elaborated a measureable dependable view of nature based on computation and calculation. To a large extent this was admirable. But the Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1886-1968) had taught Torrance the radical Christian claim that with Jesus coming into the world as a human being (the Incarnation) material reality had been shown to be more complicated than early physicists of the 1700s had assumed. The Incarnation showed the bias towards unpredictability, what Barth called the breaking into time of eternity, the intrusion of super-nature into Nature.

In other words the age-old Christian teaching of God becoming man – the Incarnation – provided an insight into the often surprising ways God could work in the cosmos. It meant that a Galilean Jew from a backwater town in Palestine back in the First Century appearing as God in the flesh had upset all human calculations of what was possible in Carl Sagan’s seemingly silent and unresponsive cosmos.

Thus Torrance argued in Space, Time and Resurrection that early 20th century scientists by penetrating anew into the “inner connections” of relatively new fields of knowledge being unveiled across the 1800s – for example, atomic structures, electromagnetism, energy waves – these were fresh understandings of the universe from out of its own dynamic inner workings. The New Physics was more accepting of what was really there. This appealed to Torrance as a way for theologians to argue afresh the Christian teachings of the Incarnation and Christ’s Resurrection in the same way. It meant accepting the strangeness of the whole Christ event on its own terms. There were theological parallels to such new concepts as space and time being linked or the existence of invisible force fields all across the world of nature.

Said Torrance: A man shouldn’t come back from the dead, yet he did. This gives Christian thinkers, said Torrance, the right to claim an essential “higher knowledge” for Resurrection and Incarnation to take place. By arguing from the true nature of who Jesus was we could ultimately make sense of the strangeness in the Gospel narratives (Space, Time and Resurrection, 189). We could decode the Christ event at a deeper level.

A wondrous correlation was made possible by applying the research premises of 1900-1925. Yet most Christian thinkers missed it.

James Clerk Maxwell – one of Einstein's heroes. Around 1865 postulated electromagnetic fields moving at the speed of light – a godfather of the New Physics.

James Clerk Maxwell – one of Einstein's heroes. Around 1865 postulated electromagnetic fields moving at the speed of light – a godfather of the New Physics.A Wonderful Strangeness

As Alice in Wonderland might have said, the New Physics of Bohr and Einstein revealed a Cosmos getting “curiouser and curiouser.” Einstein’s first important paper in 1905 forced even Ernest Mach to admit the existence of atoms, for example (DCO, 99). Visible reality was not always what it seemed to be, as James Clerk Maxwell’s work had already shown. Connected force fields became a new paradigm for physics, revising the mathematically-based motion-based assumptions of the Newtonian worldview. Torrance saw that this new way of looking at things “lays the foundations for an integration of thought which affects the whole range of human knowledge” (STR, 185). According to Torrance the “widening chasm between the natural sciences and the humanities” could be straddled if theologians understood all that physics was now showing forth (RET, 33).

Torrance touches on an important point for Christian preachers. Too often Biblical miracles were seen as “infringements of natural law” in the older Newtonian model. Torrance counters that such laws are often “read into Nature” in the first place. Can 60,000 tons of steel float? Not normally, unless different knowledge is applied from another field to give us an aircraft carrier. Intuitions from other fields than the matter under consideration in the lab can move the scientific process forward. It took Gregory Mendel’s obscure cataloguing of plant genetics, for example, to offer the proponents of Natural Selection a mechanism to help support their theory. Higher knowledge applied from another field! Torrance applies this analogy to such “impossible” events as the Resurrection of Jesus. It would be impossible h2unless you accepted where Jesus was coming from (John 1:1-4). “And the Word (the eternal Logos) became flesh and dwelt among us.”

Aircraft carrier Carl Vinson – 100,000 tons of steel can float once higher knowledge is applied from other fields.

Aircraft carrier Carl Vinson – 100,000 tons of steel can float once higher knowledge is applied from other fields.Thus Torrance argues that the doubters on Mount Olivet at Christ’s Ascension (Matthew 28:17) were suffering from overmuch Reality, not a lack of evidence.

More There There

In theological terms, Torrance advanced the simple overarching point that the new scientific processes issuing from the New Physics confirmed how there was more “there there” than we could account for (Divine and Contingent Order, 8). As he said in an arresting quote about God’s written revelation: “God defies complete disclosure…The Scriptures indicate more than they can express” (Reality and Evangelical Theology, 140, 119). Hence the Torrance emphasis on the word “contingency,” a term denoting a superbly rational universe yet one that is still ultimately mysterious. “The intelligibility of the universe provides science with its confidence, but the contingence of the universe provides science with its challenge” (DCO, 58). Einstein himself said, “The harmony of Natural law reveals an Intelligence of such overwhelming proportions that compared with it all the thinking and acting of human beings is but an utterly insignificant reflection.” Carl Sagan too knew this.

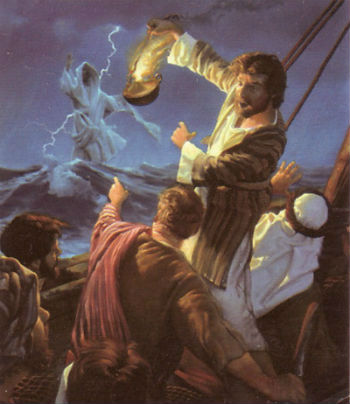

Jesus walks on water: an example of the 'wonderful strangeness' inherent in Scripture and of contingency where the natural world suddenly experiences super-nature.

Jesus walks on water: an example of the 'wonderful strangeness' inherent in Scripture and of contingency where the natural world suddenly experiences super-nature.Challenge and surprise as aspects of the divine contingence are key to Torrance’s correlation of the new science methodologies with Theology. Torrance even coins a clarifying proverb: In discussing the Resurrection of Christ, one can’t prove the supernatural by nature (STR, 22). However, one can, must, lay the claims open to rational examination and testing on their own grounds. “The resurrection itself posits the ground upon which it is to be assessed” (STR, 24). This is true. The only way Christ’s resurrection can be finally believed and embraced is by accepting the premise that the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, a cornerstone of trinitarian thinking. We then approach the Gospels with a mind-set ready to follow the lead of the inspired writers.

In this, Torrance does a great service to Christian theology, critiquing Rudolph Bultmann’s (1884-1976) now rejected overemphasis on the squashing of any miraculous events attaching to Jesus and the early church. Rather, the history of theology shows that “new modes of thought and speech” are always needed in approaching the implications of the Incarnation. The men (and women) at Nicaea in 325, for example, were forced to invent terms compatible with their subject – the strange overweening reality of the God-Man. (STR, 31). Greek terms were used in a creative way – hypostasis (the underlying reality), ousia (the God essence which explains how God is three and one), perechoresis (the interpenetration of the three essences within the Godhead effecting perfect unity).

Niels Bohr (1885-1962) probed atomic structures following Max Planck's lead.

Niels Bohr (1885-1962) probed atomic structures following Max Planck's lead.Theological-Scientific Parallels

There are thus Christian parallels to such strenuous concepts as Quantum Theory and Relativity as our scientific starters post-Einstein. The New Physics and its “outrageous legacy” of quarks and subatomic particles parallels a theological imperative to reexamine the Gospel accounts from their own premises and presuppositions. One British journal made the humorous but illustrious claim that “after quarks the Virgin Birth is a piece of cake.”

For Torrance, “bodily resurrection” patterned after Jesus’ resurrection is the unique event that defines everything else in the New Testament – what science calls the Archimedean point, where all the evidence is going, the underpinnings of the real meaning of the Universe – God bringing many sons to glory as it says in Hebrews 2:8 (STR, 42) and Romans 8 “the created world itself can hardly wait for what’s coming next” (The Message). The resurrection presupposes that we will have bodies such as we have now though of a different component – St. Paul’s “spiritual body” (1 Corinthians 15:44) or the “glorified body” of Philippians 3:21.

Karl Barth: Torrance's teacher showed how Eternity had broken into Time with Jesus, inadvertently paralleling some of the New Physics around him.

Karl Barth: Torrance's teacher showed how Eternity had broken into Time with Jesus, inadvertently paralleling some of the New Physics around him.Thus Torrance’s contemporary, Bishop N.T. Wright, also admits in The Resurrection of the Son of God, of the “strange aura” in the Gospel narratives, something that puts off many of a scientific bent today. These writings are “more enigmatic” than we think, says Wight, for even as Jesus ascended there were still some who doubted (587). But their doubts were from “an excess of reality,” Torrance has already clarified. As the scientific-minded theologian, John Philoponus had seen in the 500s AD, with Jesus leaving the heavenly realms to become the babe of Bethlehem an overwhelming new reality had entered nature, and changed it. In our day Relativity helped overturn the Old Physics or Classical Physics. Similarly “Jesus has transformed all the old conditions of life” (STR, 37). We no longer see him – or us – from just a human vantage point.

We are surprised by his resurrection, but, considering the ultimate Source of this event, the Great I Am who is also the Creator-Redeemer, it fits. Contingency makes sense of this. The Creation is logical and with an underlying order but yet capable of enormous surprises. The kind of surprises that would allow both quarks and virgin births to take place. This, as they say in seminary, will preach!