100 Years of Relativity: God and Dr. Einstein

By Neil Earle

The Cosmos is open to newness and the unexpected.

The Cosmos is open to newness and the unexpected.On the morning of November 7, 1919 a middle-aged professor at the University of Berlin awoke to find himself famous.

The London Times had published an article that confirmed the conclusions of a British expedition to West Africa. It showed that light rays photographed during an eclipse were bent by gravity in their motion.

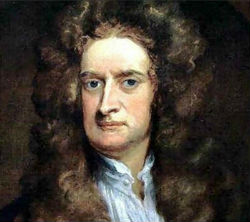

This news confirmed the theory announced in Berlin in 1915 that gravity bends light and that gravity, light, energy and time itself were all related. This was an earthquake in the world of physics. For more than two hundred years, Sir Isaac Newton’s theories of gravity as a constant absolute force which was the same everywhere in the universe had encouraged the notion of a complex but static universe, a closed system of cause and effect. Newton built on Euclid’s Greek physics of universal straight lines and right angles even while emerging science showed that on a curved surface such as our globe, straight lines converge at the poles.

What’s up? Things were not as simple as the Newtonians were saying.

Sir Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton“The New Physics”

Newtonian or “classical physics” had had a good run. By its stress on cause and effect, precise measurements and dogged investigation of phenomena it contributed immensely to the technical advances of the 1700s and 1800s that made our world a better place. But classical physics could not account for some bothersome anomalies such as Mercury’s slightly irregular orbit. Even the earth’s journey around the sun was not exactly 365 days each time. Perfect precision in the post-Newton world was proving impossible.

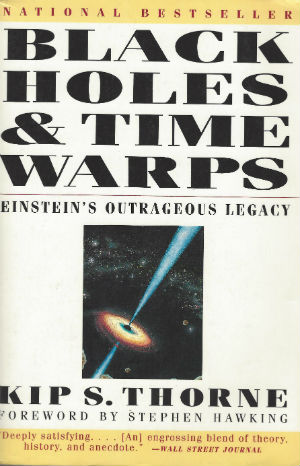

Some years before, this same Berlin physics professor had proposed that not only light but time itself was deflected by the gravitational field. As Kip Thorne of Caltech explains: “Time did not work the same way all through the universe. Time is relative to where you are, how fast you are going and the power of the gravitational pull.” Time could be curved, an idea which gave way to such teasing limericks as

You hold that time is badly warped,

That even light is bent;

I think I get the idea there;

If this is what you meant;

The mail the postman brings today,

Tomorrow will be sent.

Nature’s effects were thus relative to where you were at any given point in time. Then in November 1915, the Berlin professor unveiled his ideas on what he called “General Relativity.”

Relativity at 100 – what did it all mean?

Relativity at 100 – what did it all mean?The Light-Bender

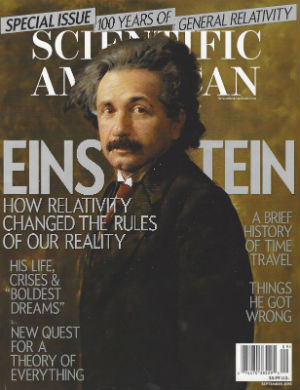

The insightful physics professor, of course, was Albert Einstein and the year 2015 marked 100 years since his ideas on what is called “General Relativity” began to transform the world of physics and with it, almost everything else.

Relativity introduced the New Physics of Einstein and his generation. The notions of time slowing down near the speed of light and of bodies being elongated at that mark seemed to be out of Alice in Wonderland. But, no. Rather, it was the long-held mechanistic “closed universe” of the Newtonians that needed revision. So, in 1915 the New Physics advanced and Relativity began to be utilized in many ways. For example, even the GPS systems in our cars must account for the relative time dilations between earth and orbiting satellites.

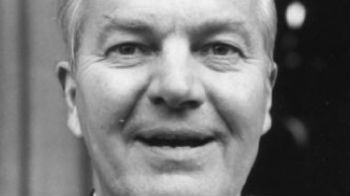

In the field of religion, however, it was not till later in the 20th century did the theological implications of the New Physics become clear. This was thanks largely to the work of a Scottish “scientific theologian” named Thomas Torrance. Let’s look at two of his key ideas.

The Great Clockmaker?

First, Torrance realized that Einstein and his generation were presenting a new view of reality. Relativity – building on late 1800s experiments with electromagnetism and atomic theory – were opening up a whole new world to those willing to look. Contrary to the classical view that God had been a great Clockmaker who wound up the universe and left the scientists to explain it through uncovering nature’s infallible laws, Einstein’s linking of space and time (space-time) pointed to a more connected and relational view of how the universe worked. This is much more in harmony, argued Torrance, with a cosmos called into being by a Father and a Son held together through the all-powerful word of the Spirit (Genesis 1:1-3).

Thomas Torrance

Thomas TorranceOne implication was that just as unseen forces such as electromagnetism held together the empty spaces in the atoms that make up humans and galaxies, the most important forces were invisible. Torrance saw the resonance between this reality and Colossians 1:15-16, “He is the image of the invisible God…for by him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible…all things were created by him.”

With relativity’s effects in view, Torrance asserted a “combination of unpredictability and lawfulness found in nature.” Nature was both dependable and yet open to change, open to intervention from outside. Even nature’s bias to order had enabled Christian critics of the “absent Clockmaker” theory to quote Hebrews 1:3. There it says ,Christ is “sustaining all things by the word of his power.” The neat and precise Clockwork school did indeed have a hard time encompassing all reality. Nature gives us the Swiss Alps, yes, but also avalanches and ice storms. There is order, yes, but we know now there is also a bewildering array of invisible things that challenge physicists – things such as dark matter, dark energy, time dilations, antimatter and the like. “The frontiers of science are filled with uncertainty and confusion,” admits Nobel Prize winner Leon Lederman of the University of Pennsylvania. ”Every step forward is accompanied by new mysteries. Science lives with its uncertainties.”

The big 100 ideas

The big 100 ideasDethroning Natural Law

Most laymen are not aware of these dynamic and often bewildering trends in modern physics. Of course there are still continuities. Gravity keeps us from spinning off into space along with other forces, which Einstein still saw as fundamental. But Einstein and his colleagues had indirectly freed science from the tyranny of what came to be called “Natural Law.” Newton’s adherents (more than Newton himself) postulated that the Bible’s references to miracles could not be true because of the fixity of natural law. “God’s interventions contradicted his own rationality,” it was charged. This confident conclusion of Enlightenment science appeared to checkmate belief in a Sovereign Creator who works resurrections and clams storms at sea.

To those who argued that the cosmos was a closed system and its workings were determined by natural law, relativity and the new quantum world came as a shock. Einstein and his generation were undermining this hyper-legalism of science by postulating a world where the invisible – atoms, time dilations (the slowing of the flow of time near a gravitational body), and the fields binding particles – were as powerful, if not more powerful, than the visible.

The more the New Physicists explored the invisible realm the more complexity and mystery they saw. All this brought the New Physics into tension against the overuse of Natural Law. Torrance argued that God’s “mighty acts” in space and time were paralleled by the need for physicists to strengthen their insights from outside their particular speciality. Torrance showed how Charles Darwin had to “prove” natural selection by bringing in the Catholic priest Gregor Mendel’s experiments with plant biology. Relativity’s more intense focus on powerful invisible forces brought into nature to correct or enhance the natural world meant that God was not violating natural law in the begettal of Jesus through the Holy Spirit (the Incarnation), but that he was bringing more powerful knowledge to bear on certain situations, as had Darwin from Mendel.

Can 60,000 tons of steel float? Never, unless...unless it was shaped and molded and worked on by superior knowledge to produce an ocean liner.

Cal Tech's Thorne probed Einstein's legacy.

Cal Tech's Thorne probed Einstein's legacy.Respect for Mystery

There is a second reason Torrance argued for the “congeniality” between theology and the New Physics. Einstein had seen that contemplating the complexity of creation called for an attitude of humility. He himself said that “the universe in its profoundest depths is inaccessible to man.” This squared exactly with the insights of the wise man in the biblical Book of Ecclesiastes. “As you do not know the path of the wind, or how the body is formed in a mother’s womb, so you cannot understand the work of God, the maker of all things”(11:5).

Though Einstein’s own views on religion are often debated, he did not hesitate to talk of the Old One (his name for God). He publically wondered aloud about the cosmos and how he could “think God’s thoughts after him.” On more than one occasion he expressed awe at how the Creator had put things together, suspecting the answer was ultimately beyond him. The stories of Newton’s apple and Watt’s steam kettle may be exaggerated but are an echo at the popular level of what Einstein saw as the indispensible element in true science: the respect for mystery and unpredictability, a deep awe in the face of the incomprehensible Intelligence of the Old One (CISE Bulletin, page 9). Einstein often admitted “the mysterious comprehensibility of the universe which is yet finally beyond [man's] grasp” quotes Torrance in Theological and Natural Science (page 31).

Einstein himself modeled humility in his waiting four years for his relativity theory to be demonstrated in 1919. Likewise Torrance encouraged theologians and Christian teachers to examine anew such Biblical teachings as the Incarnation and the Resurrection of Christ but from the position of what N.T. Wright calls the “strange aura” in the Gospels – the commanding and decisive personality of Jesus himself. To miss that is to miss the whole game. If we ask biological questions about the virgin birth, says Torrance, we will end up with awkward biological conclusions. If we ask strict historical questions about the Gospels, we will end up ultimately boxed into a corner. Torrance encouraged a humbler and profounder reexamination of the Biblical texts in the style of the new reexaminations of reality that hit the world in 1915. The fact is, he argues, that the creation issuing from God’s hand was open to newness and even unpredictability (Isaiah 43:19).

Torrance’s teacher Karl Barth reiterated that the Bible is a strange and wonderful book and must be met on its own terms rather than the way historians and anthropologists have chosen to see it. This needs constant stressing with today’s knowledge explosion.

An “Open” Universe

For a larger fact is that, as Torrance knew, scientists could not ultimately explain the “why” of the universe in its unfolding immensity. He called for Christians to offer a Biblical-based concept of purpose and intentionality behind the creation. “Now since God has endowed his creation with a rationality and beauty of its own,” wrote Torrance,” the more the created universe unfolds its marvelous symmetries and harmonies to our scientific inquiries, the more it is bound to fulfill its role as a theatre which reflects the glory of the cosmos and resounds to his praise” (Reality and Evangelical Theology, pages 10-11).

The universe as “a theatre of God’s glory” is an elegant metaphor for Torrance’s call to see an invisible God behind the created order. If Noble Prize winners and even Albert Einstein was ultimately baffled by the size and scope and unintelligibility of the vast cosmos, scientifically-minded Christians should feel less constrained about setting forth a Romans 8:19-22 interpretation of the cosmos. These and other texts show, concludes Torrance, that we have a created universe purposely endowed with an independence from its Creator, open to surprise and new possibilities such as Einstein set forth in 1915. The cosmos is free to develop, so free that frustration and purposelessness are often bewildering side-effects (Romans 8:20). But also the universe is open, free and unpredictable enough for the Creator/Redeemer to enter our world of space-time as the child of Bethlehem

The New Physics showed there is more “there there” than we had thought. Greek ideas of a dark uncaring Fate and the Enlightenment fixation on natural law have been checkmated as satisfying theories of origins and destiny. Instead, Torrance called for a refashioned Christian answer and purpose to the universe inspired by insights set forth in the style of Dr. Einstein. This sometimes baffling universe is open to God’s intervention as “the creaturely medium through which (the Creator) makes himself known to mankind” (page 11).

Einstein, the architect of Relativity 100 years ago, unlike some in physics today, was never slow to admit when things were beyond him. He thus unwittingly applied the wisdom of Proverbs 25:2, “It is the glory of God to conceal a matter; to search out a matter is the glory of kings.” Thanks to the fall-out from Relativity and the insights it set in motion, today’s theologians can be much more confident to show how God can both stand outside the cosmic picture and yet still step inside it.