Dixon Bible Exhibit: A Hopeful Encounter in Vermillion and Gold

By Neil Earle

The Saint John’s Bible has inspired thousands worldwide. The exhibit was featured at Memphis’s Dixon Gallery & Gardens, Oct. 11 - Jan. 10.

The Saint John’s Bible has inspired thousands worldwide. The exhibit was featured at Memphis’s Dixon Gallery & Gardens, Oct. 11 - Jan. 10.“Memphis, Tennessee, where nothing happens except the impossible” was Robert Gordon’s tribute to our multifaceted city in It Happened in Memphis.

Sunday January 10, I left the Dixon Gallery and Gardens feeling I had experienced another Memphis “impossible “moment. The Dixon’s prestigious venue was imaginatively transformed into a contemplative shrine for the World’s Most Famous Book. From October 11 to January 10 the Dixon team had hosted 68 page panels from The Saint John’s Bible Project, a product led by Benedictines from Saint John’s Abbey and University in Collegeville, Minnesota.

On show were excerpts from the first handwritten illuminated Bible produced in some 500 years, a mission to recapture the craftsmanship of the manuscript productions of the Middle Ages enhanced by modern technology. The decades-long project was completed in 2011 and involved collaboration between a scriptorium in Wales, 23 professional scribes and artists, and collocations of systematic theologians, text specialists and church historians. The result was 1127 pages of text and 160 original artworks, all to re-present the world’s most famous text, from Genesis to Revelation.

Lofty Goals

One of the goals of this massive trans-Atlantic project was “inspiring the spiritual and physical memory of God’s people around the world.” British calligrapher Donald Jackson, Artistic Director of the project and scribe to Queen Elizabeth, testified on video: “The continuous process of opening and accepting what may reveal itself through head and heart on a crafted page, is the closest I have ever come to God.”

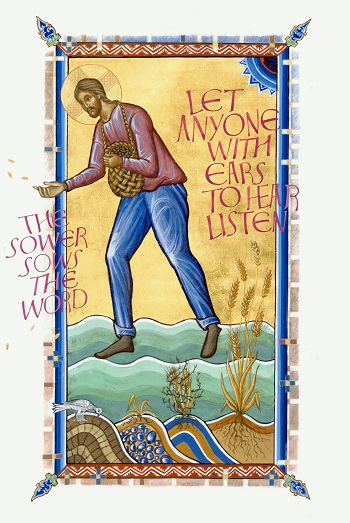

The Saint John’s Bible: Sower and the Seed

The Saint John’s Bible: Sower and the SeedFor decades, the paintings at the Dixon invite audiences to “transcend their own experiences and dwell in the realm of the beautiful.” The dozens of visitors at the Dixon’s final display on January 11 ranged from all age groups and seemed genuinely humbled by the 160 large-scale folio sheets affixed to the walls at eye level, taken with, in the words of Curator Julie Pierotta, what many reported as “the sense of a contemplative experience.” The blending of striking illustrations of Biblical scenes in vermillion, gold and deeply penetrating lapis lazuli can do that. The seven strips that began Genesis One, for example, opened with a vertical strip of tangled brown-black brush-strokes depicting original chaos but which led to a pleasing six-fold sequence depicting the reordering of creation.

That’s one hallmark of the Bible’s longevity, its penchant for order over chaos, reassurance while not ignoring the absurd element in creation. “Creation is tied to counting” read the wall plaque and this emphasis on numbers indicated a sense of divine control amidst the human turmoil showing up in later panels from books such as Job and Revelation. It was a needed reminder in our tortured winter of 2020-2021. As if to underscore the ultimate happy ending, the last display room ends with John’s vision of the City Foursquare, the New Jerusalem. Its balancing 12, 12, 12 patterns point symbolically to a perfectly recreated Universe in that blessed consummation the Bible has envisioned for the cosmos – a hopeful encounter indeed.

The mundane thought “everything here is on the level” strikes one when perusing highlights of the apostle John’s vision: a foursquare theme opening with a spectacular square logo of deeply-blue lapis lazuli lettering introducing the last controversial Book. The one discordant note in this imaginative tableau was the appearance of battle tanks and oil rigs and drilling tools accompanying the text to support the dreaded Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. This may have bothered any employee or shareholder in the energy industry and was the one incident of “special pleading” the project could have done without.

“Tender Mercies”

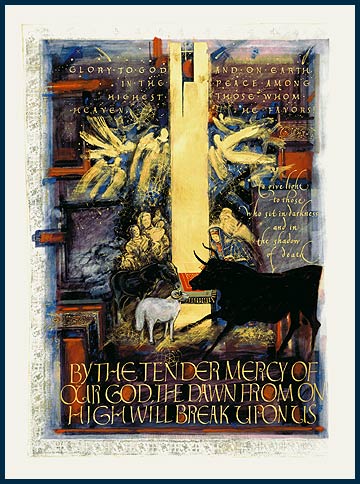

Elsewhere the brilliant opening to the New Testament exhibit where Matthew’s, the First Gospel, is ushered in with letters of vermillion and gold. The bright colors set up the attempt to reimagine “one of the most hopeful and beautiful” messages to reach human ears. Luke’s panel highlights “the tender mercy of our God” just as “the darkness did not overcome it” from the Book of John hits again the theme of hopeful reassurance. Indeed the contemporaneous feel given off by artist Thomas Ingmire’s stylized vision of earth from the Hubble telescope depiction reminds us of the Bible’s unique penchant for encompassing all of time and space, from here to eternity. It also reemphasized that this project was a blending of the medieval with the technological.

Turkey quills, egg yolks and digital imagery blended together conveyed a sense of standing outside time. That sense of moving from the sublime to the earthly showed in the “marginalia,” those minute editorial additions to a manuscript of the kind brash medieval copiers employed to leave behind some not-so-secret identifying traces. Thus, the Dixon display of the Book of Hebrews featured corners of text with small Minnesota dragon-flies resting on Yorkshire Fog Grass to remind us of the project’s terrestrial origins – hitting the celestial while remaining “of the earth earthy,” as the old Book says.

The Saint John’s Bible: Luke Frontispiece

The Saint John’s Bible: Luke Frontispiece“Visio Divina”

What of that lofty announced aim to “inspire the spiritual and physical memory of people around the world?” This seems like a lot to bite off in our somber, skeptical times.

Benedictines might reply that, we have an answer. One reason the Saint John’s Project was conceived was to use the Illuminated Bible to practice what they call “Visio Divina” or “sacred seeing.”

This involves the devotional practice of reading, mulling over the words from a passage, re-reading, repeating a striking phrase to yourself and then going back to the text in order to begin a prayer telling what has moved you in the passage. In true medieval fashion, where people “seemed” to have a lot more time, the student is finally urged to meditate briefly before learning to quietly rest in God. The practical effect comes in when an answer forms as to how the experience will help the quiet seeker face the day. The answer unfolds like the opening of a flower more than that of turning to an automatic can opener. Surprisingly, the flavor of such a spiritual exercise can be experienced in a 14-minute practicum found on more than one YouTube site.

Not having the time to devote to such an exercise of course means – we can hear a wise Benedictine say – that we will never know if it “works” or not. There is our dilemma in our sped-up times. As an African pastor reminded me: “So many watches, so little time!”

The Master Text?

For millions the Bible itself as read in the Western world gives off the aura of a supreme human-divine composition, the master text of the Western world. No less a personage than Napoleon Bonaparte is supposed to have called it “a Living Creature with a power that conquers all that oppose it.” This from a most practical man!

The Saint John’s Project strives to summon forth some of the Bible’s other-worldly profundity. The basic text is, after all, a book being translated into hundreds of dialects and tongues even as we read these words. The collaborative spirit that surcharged the Project offers evidence of the things humans can accomplish when in search of more transcendental aims. Here in our own city of rich cultures we were offered a testament in calf-skin (vellum) to some of the most lasting words and thoughts ever recorded, a small participation in one of the signal publishing events of the 21st Century so far: the Saint John’s Illuminated Bible Project. Thanks to the team at the Dixon for midwifing this spiritual encounter, for giving us a brief reminder of the infinite, of being rooted to this world while occasionally slipping those surly bonds of earth.