Civil Rights 2.1: The Challenge of Incarceration

By Neil Earle

James Forman Jr.

James Forman Jr.“Mass incarceration is the civil rights issue of our time.”

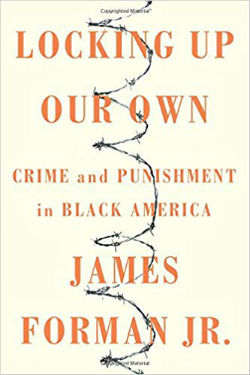

The speaker was James Forman, Jr. of Yale University at the University of Memphis on January 31, 2019. The event was sponsored by The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change. The topic was Forman Jr.'s 2017 book “Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America” which advanced the thesis that the disproportionate impact of long prison sentences on African-America communities was due not solely to whites but also by the exasperation of some black leaders demanding action to reduce crime in their cities.

Restorative Justice: an old idea whose time has come?

(ED: Former colleague, the late John Halford reported in 2010 on a British crime-fighting initiative based upon the concept of Restorative Justice.) John Halford

John HalfordCritics are worrying that the new initiative will allow offenders to play the system and get off the hook with a glib apology. Maybe some will. But let’s not be too quick to dismiss the idea. It gets to the heart of what is wrong with the present system, and it deserves to be given a fair try.

Restorative justice is more than just getting an offender to say ‘sorry’. It also provides the victim with a chance to get closure on the trauma and turmoil that is usually the aftermath of violence. As the modern state developed, the administration of law moved away from the local level. An offender’s act is breaking the ‘law of the land’. His offence is against ‘society’. The actual victim of the crime might be called as a witness, but otherwise is not involved. Offenders are punished to ‘repay their debt to society’, but are not held personally accountable to their victims, who are often left angry, frustrated and wanting revenge.

But a thief or a mugger not only breaks the law. He may also have broken your window and perhaps your nose. Under the Restorative Justice initiative offenders must agree to face-to-face meetings with their victims, and see first hand the impact of what they have done. They will be expected to pay compensation to victims, offer an apology for their actions and perhaps do unpaid community work.

The idea behind Restorative Justice is rooted in the system of law given to the people of Ancient Israel. Many Old Testament laws and regulations seem quaint now, but they were designed to produce a law abiding community based on justice, mercy, fairness and above all shalom.

‘Shalom’ means so much more than just ‘hello’ and ‘goodbye’ in Hebrew. It means people living together in harmony and safety, in a local community where everyone is valued and respected. When a crime was committed, it was not just a matter of punishing the offender to satisfy the demands of the law. The community’s ‘shalom’ had been hurt and needed to be restored. The lawbreaker had not ‘repaid his debt to society’ if those he had specifically hurt by his actions were still economically disadvantaged by their loss or smouldering with resentment and plotting revenge.

This was not a system soft on crime, or a free-for-all in which people took the law into their own hands. Justice was carefully administered, and severe crimes were massively punished. Lesser offences were dealt with appropriately, with the emphasis on having the punishment fit the crime. It placed the victim at the centre of the action. The offender had to “make good” his offence, and an effort was made to restore the relationship between him and his victim. The victim was expected to show a spirit of reconciliation and forgiveness: ‘Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against one of your people, but love your neighbour as yourself’ (Leviticus 19:18).

The goal was always reconciliation and the restoration of ‘shalom’.

Will this work today? Obviously many of the specific details applied to an Iron Age agricultural society. But that is no reason to casually dismiss the principles behind them. Times change but not human nature. Throwing more people into already overcrowded prisons, while the victims continue to suffer is clearly not the answer. Restorative Justice deserves to be given a chance.

Forman echoed claims made by former Justice Anthony Kennedy that “our [prison] resources are misspent, our punishments too severe, our sentences too loaded.” A San Francisco Federal District Judge actually broke down in court for being “forced” to sentence an Oakland longshoreman to ten years without parole after unwittingly giving a ride to a drug dealer.

The Prison-Industrial Complex

Listening to Forman speak I was reminded of a December, 1998 Atlantic magazine piece by Eric Slosser titled “The Prison-Industrial Complex.” Even then America’s prisons were becoming “factories for crime” thanks to the “privatization of the prison system.” Slosser excoriated both Democratic and Republican politicians for posturing as “tough on crime” for their own electoral benefit. Slosser highlighted the sometimes draconian sentencing that had evolved to deal with the drug crisis.

1998 was before today’s “bizarro world” where violent crime keeps dropping but the nation’s prison population keeps rising. And how. When Slosser wrote, the prison population was headed for 2 million. In 2010 civil rights advocate Michelle Alexander in The New Jim Crow, reported the number of inmates exceeding 2.3 million and growing. Alexander added that the number of blacks now attached to the prison/probation/parole network exceeds the number held in slavery in 1850. Larger than those held in jail under apartheid in South Africa.

Forman reemphasized this to his Memphis audience: America has become the prison capital of the world with 5% of the world’s population holding 25% of the world’s total inmate population and 1 of 3 young black men tied in to the criminal justice system.

Treatment or Sentencing?

By 1978 drug offenders made up twice the number of all other inmates held in prison. When Slosser wrote, Californians alone exceeded the number of inmates held in France, the United Kingdom, Japan, Singapore and the Netherlands combined. By 2010, claimed Alexander, America’s prison population exceeded Russia and China’s combined and seven times that of Germany’s. “A human rights nightmare,” says Forman.

Michelle Alexander

Michelle AlexanderToday there is renewed attention being focused on this national scandal, largely through the costs involved to the state. A night in prison costs more than a night at the Marriott. The Memphis Flyer of January 31, 2019 documents the reaction from lawmakers against overly harsh penalties and “mandatory minimums” for non-violent drug offenders. Sentencing overwhelms efforts at rehabilitation. Once a family member receives a sentence for drug dealing their chances at receiving government assistance, school scholarships, etc. is greatly reduced.

In his riveting narrative Don’t Shoot, Criminal Justice reformer David Kennedy traces the change back to the Rockefeller Law, pushed in New York State – part of the “law and order” backlash against the first wholesale drug epidemic in the 1960s. The Rockefeller Law of January 3, 1973 imposed the mandatory prison sentence of life without parole for drug dealers (even juveniles). At the time New York State had its lowest prison population since 1950. In 1970, paradoxically, the U.S. Congress ruled that drug addiction was seen as a public health issue more than a criminal justice issue. That is, as late as the 1970s, society stressed prevention and treatment as the better path forward.

In 1977, I remember famed entertainer Art Linkletter telling an audience of counselors at Pasadena, California the blindingly simple truth that “people take drugs because they feel bad.” Linkletter’s own daughter was a victim of a drug overdose. The respected humorist was stressing early detection and follow-up counseling. Comedian Carol Burnett took up the cause in the 1980s. But then came the crack epidemic and another “great fear” that swept Middle America.

The “War” on Drugs

Even liberal-minded politicians such as House Speaker Tip O’Neill spearheaded the restoring of mandatory minimums with the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. Then came New York’s state’s fateful decision to sell Attica Prison to a group named the Urban Development Corporation: a signal event in the virtual privatizing of the American prison system which has led to the scandalous “school-prison pipeline” that Forman mentioned – corporations arrogantly building jails conveniently located close to schools where juveniles can first get into legal trouble.

By the 1990s, reported Slosser, some small towns had more inmates than regular folk. Economics, as always, plays a huge part. From 1984 to 1994 California built eight new maximum security prisons while public housing projects languished. Forman reported how the GM plant in one of his hometowns has closed while a new wing has been added to the local penitentiary. More and more jobs were tied to incarceration.

In his Q and A Forman dealt with that as a real issue, citing a pilot program he worked on that turned correctional officers into tutors. Today real efforts are underway to turn prisons into much-needed vocational and schooling plants instead of lock-ups. Forman described the “Inside-Out” program gaining traction where seminars are conducted with students visiting prisons to interact with classmates doing time. One successful inmate told Forman, “I was finally treated like someone smart.” Rand Corporation estimates that for every $1 spent on prisoner education society gets $5 in return. Smart economics.

Curious Case of the Cartels … or Who are the Real Perps?

Sadly, some inciting causes of the crack cocaine explosion in the inner cities during the middle 1980s have been virtually obscured. In Don’t Shoot, David Kennedy, confirmed what Alexander knows and respected journalist Haynes Johnson reported in his insightful 1992 work Sleepwalking Through History. The Columbian drug cartels – much in the news these days – exploited the Iran-Contra machinations of the 1980s. Weapons were shipped to Nicaragua (illegally) largely through the Colombian drug cartels with Panama’s dictator Noriega as middle-man. Human nature being what it is, this had a tragic backfire effect – empty planes returning dumped tons and tons of Colombian cocaine in the United States. Haynes Johnson showed how “pilots flying these missions included Americans, Colombians, and Panamanians (pages 167-168).Of course, this does not excuse the consumption or sale and use of crack on our streets. But it does remind us of the complexities involved and how society is a seamless web. We are all implicated.

Untangling the Dilemma?

Art Linkletter and Carol Burnett were voices spotlighting the human side of these tragedies. In 1998 Slosser forecast the essential step that Michelle Alexander and other community leaders are warning about: “Crimes that in other countries would usually lead to community service, fines or drug treatments – or would not be considered crimes at all – in the U.S. now lead to a prison term.”

Professor Fred Frese of Northeastern Ohio University and a former Marine captain says we can’t afford the status quo. “Imprisonment is by far the most expensive form of punishment.” One hundred dollars a day compared with $35 in a group home.

Forman, a former Public Defender, gets back to the human side of this equation. Sympathetic people should serve on juries, he argued rather than abdicating decisions to the “12 Angry Men” from the famous Henry Fonda movie. He urges citizens to go door to door to help elect progressive prosecuting attorneys and judges rather than repeating the status quo. Forman believes in the concept of Restorative Justice, being tried in more and more places (see Box above left).

Overall James Forman Jr's message hit a timely chord. Slosser’s 1998 argument had a hard-hitting conclusion: Does the country that built the Panama Canal, Boulder Dam, and the Interstate want to be remembered for constructing Stalags across the heartland? Slosser’s bold indictment of the “fear, greed and political cowardice” that has accentuated this growing scandal reminds us of the cost to all of us when shortcuts and blame-placing obscure true justice.