Was God Dead or Were Christians Just Dozing?

By Neil Earle

Budding journalist (and skeptic) Neil Earle, B.A. 1966.

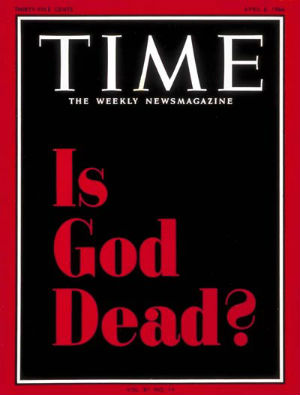

Budding journalist (and skeptic) Neil Earle, B.A. 1966. Time Magazine cover from April 8, 1966

Time Magazine cover from April 8, 1966Our news-hungry times seem to be attracted to anniversaries of great events. This year, 2017, will see the 150th birthday of my home country, Canada, and the 100th for the National Hockey League. For Christian journalists such as myself I was intrigued how April 8, 2016 passed unnoticed. That was the 50th of the April 8, 1966 Time magazine cover, “Is God Dead?”

The title “Is God Dead” – almost 50 plus 1 years ago – came in the middle of a decade comprising what a journalist later called “The Tumultuous Years.”

The years leading up to 1996 had been notable for certain things if you grew up in British countries. There were the Profumo sex scandals in “Swinging England,” the debate over “Lady Chatterly’s Lover,” the Pill, the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Kennedy Assassination in America, the Canadian dollar plunging to 92.5 cents in 1963, the doctors strike in Saskatchewan protesting the extension of welfare, Lester Pearson’s new Canadian flag debate and – on the religious scene – the paperback edition of Anglican Bishop John A. T. Robinson’s “Honest to God” in 1963.

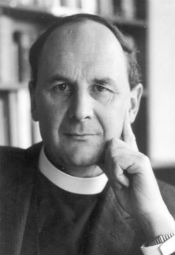

Bishop John Robinson

Bishop John RobinsonWhat a shocker for us button down Anglican types. “Honest to God” was like a high-level clerical bull session where the Bishop of Woolwich aired publically his sincere doubts about such allegedly Christian distinctives as the Virgin Birth, the Resurrection and the divinity of Jesus.

“The Comfortable Pew”

It was a time – the mod-Sixties – when the foundations did seem to be shaking.

Two years after “Honest to God” the Anglican Church of Canada forthrightly sponsored the respected agnostic journalist Pierre Berton’s critical analysis tilted “The Comfortable Pew.”

Meanwhile, the Very Reverend Angus MacQueen of the United Church of Canada criticized his church as “too pietistic and irrelevant in the face of the real stuff of life and the very real issues of the day.”

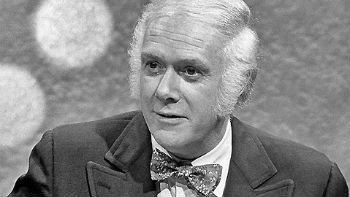

Pierre Berton

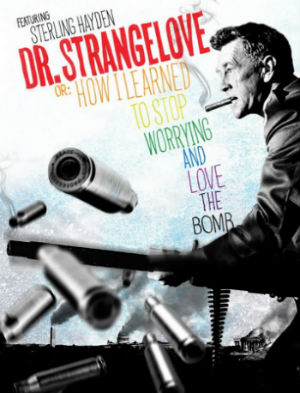

Pierre BertonRelevant was an operative word in the 1960s and the atmosphere of threat was tangible. Presidential historian Michael Beschloss was not far off the mark in describing that period as “The Crisis Years.” The 1964 dark comedy film “Dr. Strangelove or How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” had originally been planned as a serious drama about accidental nuclear war but the images of B-52 bombers loosed on Russia were thought too harrowing for the mass audiences of the time.

These artifacts of the popular and religious culture may seem somewhat lower-keyed in our media-bombarded and over-communicated age where everything seems to be happening at once. But the very slowness of the news cycles back then – in comparative terms – made dramatic events even more dramatic, or so it seemed. I remember trudging home from classes at Memorial that sober autumn of 1962 to ask my landlady, “Have the Russian ships reached the American ships yet?” The Cuban Missile Crisis is a baby boomer touchstone and Gen X may well roll its eyes but at the time – well…

The Evangelical Revival

As it turned out, God was not dead and the shocks of the 1960s spilling into the 1970s served to reawaken a quiescent evangelicalism. This was especially true in the United States where the abortion decision enshrined in Rose vs. Wade in 1973 galvanized a part of the religious community some felt was half-asleep.

Today’s evangelical wing of American Christianity helped elect three presidents, Reagan, Bush 43 and Donald Trump. And Canada’s more muted response was summarized in a 1990 book by journalist Ron Graham on Canadian religion titled “God’s Dominion: A Sceptic’s Quest.” Graham was incisive on the state of religion a generation back: “For all the talk of Canada as a secular and materialist country…hardly a day passes without a front-page headline directly or indirectly about religion: abortion…provincial debates on religious instruction in the schools, church groups opposing free trade, cult activity…”

These issues have their parallels in the year of grace, 2017, if we add attacks on Islamic mosques, Christian beheadings in the Middle East, Anglican churches that have seceded from the worldwide fellowship, and a steady stream of candlelight vigils and televised church services when tragedy strikes. We can conclude perhaps even more forcefully that – to paraphrase Mark Twain – the death of God as a subject of popular discussion has been greatly exaggerated.

The Big Questions

Both Graham’s synopsis and conclusion seems as relevant now as it was then. The religious aspect of our lives, said Graham, stems from three factors. Some of it comes from the world at large, some of it a leftover from ideas and battles of the past, “and some of it exists because the great questions of being, meaning and dying can never go away.”

This reporter felt then and feels now that Graham got it tight. Those fundamentally great questions never do go away and in spite of body blows from the New Atheists in the early years of the century – Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins – the Faith survives. A French king was once zealously persecuting a fringe sect of the church and asked his cardinal for advice. “The church, sire,” said the cleric, “is an anvil that has worn out many hammers.”

Looking back, this seems as true in our even more tumultuous times.