Why the Queen Keeps Remembrance Day

By Neil Earle

Queen Elizabeth served as a mechanic during World War II.

Queen Elizabeth served as a mechanic during World War II.You may have noticed that Queen Elizabeth II – one of the world’s most notable figures – was ordered to rest up at her age of 95 from her many public duties but the Palace opined she’d be able to perform her state functions by Remembrance Day – November 11. This date commemorated the end of the enormous blood-letting known as World War One from 1914-1918.

The Queen, who served as a volunteer in the Second World War (1939-1945), was not about to let this event slip. “World War One changed everything,” says Niall Ferguson of Harvard.

This is no overstatement. World War Two cemented American dominance in the world but the process was already set in motion by the world-shattering “war to end war” as the first grim conflict was promoted.

The Bittersweet Legacy

“Little Arlington cemeteries” dot the French landscape to pay homage to the honored dead. One million died from British countries alone. In 1918 my hometown of Carbonear, Newfoundland (pop. 4300) installed dozens of banners picturing veterans of both world wars prominently along the main street. All across the British Commonwealth you will find more monuments to that awful first war than the one that followed. The casualties were psychologically more shocking due to no one expecting such carnage.

The bittersweet legacy haunts our daily news. The Middle Eastern crisis of today traces in quite some measure to the unreality of the present-day borders in the region. The straight lines demarcating Syria, Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia shows us how much of an unreality some of these nation-building attempts were, conducted by the victors in Paris after the war. Sometimes the alternatives were not all that rosy.

Even today’s borders in Western Europe took modern shape as a direct result of the horrendous bloodletting that raged from August, 1914 to November, 1918 in Europe and drew in most of the known world (America joined in April, 1917).

A Blizzard of Empires

French and British policy-makers at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919 were in fact carving up one of the four great empires that collapsed during the fiercest conflict mankind had yet waged. Present-day states such as Iraq, Syria and Iran took root from the fall of the Ottoman Empire (1453-1922). This was a 400 year-long Turkish Islamic imperium over most of what we call the Middle East. Iran was outside that orbit which helps explain some of Tehran’s independent thinking to this day.

In 1917 the British took Jerusalem and intruded themselves into the Middle East. They achieved dominance in today’s Iraq, present-day Jordan and the area then known as Palestine. The French dominated Lebanon and Syria. Beirut became known for a while as “the Paris of the Middle East.”

And all because of a quarrel between the Great Powers of Europe over the contentious ethnic and religious rivalries in the Balkans, the spark that dragged the nations into war in August 1914.

The Terror Connection

Even latter-day terrorism figures into the picture. Most historians know that few things are as dangerous as an empire in decline and by August, 1914 this condition applied to three transnational systems – the Ottoman, the Austro-Hungarian in the middle of Europe and the Russian Empire of the Tsars.

Terrorism reared its ugly head when a Serbian nationalist assassinated the Austrian Arch-duke. Austria demanded revenge. Tsarist Russia backed Serbia in Moscow’s self-exalted role as “mother of the Slavs.” Germany had an alliance with Austria and Russia was tied to France and France was allied with England. Thus when the Austrian-Russian tension blew up because of conflict in those boundary lands of Eastern Europe – rife with ethnic and religious conflict – the match was lit and the guns of August began to erupt.

It is not that war was inevitable in August, 1914, it was just that when Germany, feeling encircled, felt it needed to strike first and plough through neutral Belgium, then British felt it had treaty obligations with the French for defending Belgian neutrality.

By August 4 Britain had declared war and the United States – trying to stay out of it – would get inexorably involved when German submarines began sinking American ships selling supplies to Western Europe.

America Rising

This was once the stuff of our history classes. The effects of this “suicide of Europe” would fall far and wide.

While Europe tore itself apart, most financers and creditors needed a safe place for their investments. The United States soon became the leading creditor nation in the 1920s as exemplified by the building of the Empire State Building in 1929-1931. Financial power had shifted and with it much of the world power, though Britain and France were still big players up till World War Two’s outbreak in 1939.

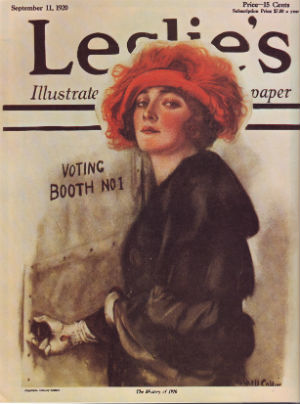

A sharp recession in 1920-1921 as the economies painfully shifted from machine guns to washing machines disillusioned many who fought. This created a mood of isolationism in America and out and out appeasement in Europe that hastened the rise of the Fascists in the 1930s. Wars do indeed have consequences. Canadian women got the vote in 1917 and Americans in 1920. Los Angeles noted that the newly rising film industry was almost suspended in Europe from 1914 to 1918 and thus a small little suburb named Hollywood came out on top. The 1920s of course were the heyday of Charles Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford and a new kind of culture arose in the Western world, one we recognize still.

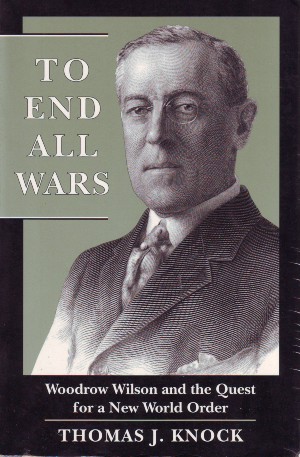

More significantly, if the Spanish-American war of 1898 had announced the United States as a major world power, the shipping of about 2,000,000 U.S. “doughboys” overseas served notice that Americans were in the Big Power game to stay. This in spite of strong tendencies towards isolation between 1918 and Pearl Harbor in 1941. In 1918 those fresh, exuberant but inexperienced American troops arrived just “in the nick of time” as Germany began an all-out offensive in March, 1918 that almost reached Paris. The exploits of the former pacifist Alvin York from Tennessee for capturing 132 German prisoners single-handed strengthened the American sense of nationhood on the world stage. President Wilson had stayed out of the war as long as he could in spite of the provocation of American ships being sunk.

The Dream of Peace

In the end most historians feel Wilson entered the war in April, 1917 in order to have a voice at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. Wilson’s adopting of a British idea for a League of Nations was defeated back in the United States Senate but the concept of some form of world organization never went away. When the next attempt arose during World War Two, President Franklin Roosevelt made sure America would be in to the neck. The United Nations headquarters would be established in the United States largest city, the UNO building in New York.

The right to national self-determination affecting for the good such countries as Canada and Australia and New Zealand opened a Pandora’s Box of third world nationalism. Both the Japanese and a Vietnamese bus-boy in Paris named Ho Chi Minh felt jilted by the Great Powers in their nation’s aspirations. Those events were mighty in scope and over-weening nationalism (if not tribalism) is with us still from Africa to Afghanistan. All these moves, including the seasoning of such later American leaders as George Marshall, Douglas MacArthur and George Patton – all this together showed how much World War One had cast a long deep shadow. The effects were indeed momentous, the casualties were staggering – something the Queen’s generation has not forgotten.

“The War that Killed God”

Short skirts, women smoking, Hemingway’s wounded heroes, Freudian psychology, Bolshevism at high tide – these were emblematic of the postwar era and a reason WW1 is sometimes known as “the war that killed God.” Yet the God concept has proven more durable than some radical thinkers of the 20th century have supposed. Queen Elizabeth herself is a representative of sterling qualities of duty and public service that have stood the test of time and that rest ultimately upon religious foundations. At least multiple millions still seem to think so.

When asked once why I, a Canadian in the United States, had not yet taken out American citizenship, a Presbyterian pastor next to me blurted out: “Why should he, he’s got the Queen.”

All of this makes good reminders of the old adage that “virtue is its own reward.” Though much was taken from us in 1914-1918, much abides, and even the most merciless human endeavors come to an end. This is a truism indeed worth pondering on November 11.