Iraq and the Birth of Archaeology

By Neil Earle

The reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

The reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

All through the early 2000s I was making the point on my cable TV show in Duarte, CA that the troubled nation of Iraq – now off our radar it seems – was famous for much more than Saddam Hussein and foreign occupiers.

In fact, this stratgeic country can lay some claim to being the birthplace of modern archaeology. As evidence of this consider the Museuminsel on the Spree River in Berlin. It has been described by “The Los Angeles Times” as “the liveliest contemporary gallery scene in Europe” sure to attract European’s attention as the holiday season unwinds.

The Museuminsel hosts one of biblical archaeology’s most impressive treasures – the cobalt-blue Ishtar Gate from ancient Babylon.

The Ishtar Gate, with its stately procession of lions, bulls and dragons, links North Atlantic scholars and the present struggling nation of Iraq in a remarkable cultural embrace. How so? Mainly because this ancient entryway to the city of Babylon, apparently built by King Nebuchadnezzar himself (604-562 BC), was transported brick by brick from Mesopotamia to Germany through the efforts of Robert Koldewey and his remarkable Iraqi expedition of 1899-1912.

“The Wonder City!”

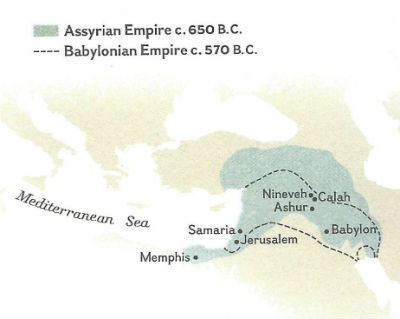

Back in the days of the Koldewey Expedition there was no such country as Iraq. Mesopotamia (“the land between the rivers”) was the possession of the tottering Ottoman Empire headquartered in Constantinople. In the late 1800s Western European powers dominated the globe. British and French archaeologists pretty well roamed at will over the highly significant territory bounded by the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers and beyond. The German Kaiser even dreamt of a Berlin to Baghdad railway.

Thus Koldewey’s remarkable foray into modern-day Iraq. His work has been praised for its “patience and ingenuity” not to mention the fact that here were the first excavators to properly grasp the challenges and opportunities posed by stratigraphy – the “layer cake” style of so many ancient ruins (Seton Lloyd, The Archaeology of Mesopotamia, page 223). Along the way, Koldewey’s researches established once and for all the historical veracity of the King Nebuchadnezzar of the Bible – and much more.

Nebuchadnezzar! The Old Testament rings with the terror of his name. Irving I. Finkel tells his story in The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World:

“[Nebuchadnezzar] was one of Mesopotamia’s most illustrious and effective kings. He pursued an active policy of extending and securing his empire, fighting campaigns in Syria, Palestine and Egypt, which, as chronicled in the Bible, led to the removal of Jehoiakin, King of Judah, and many prisoners to Babylon in 597 BC (2 Kings 24:14-16), and later to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and the wholesale removal of the Jews to Babylon in 586 BC. …Nebuchadnezzar was an indefatigable builder. A vast labor force was put to work producing …blue glazed bricks to face the most imposing monuments” (pages 38-39).

Those blue glazed bricks were the very artifacts Koldeway and his German diggers discovered on the Ishtar Gate. They offered sharp indirect evidence that the Bible’s claims about the power of Babylon and the splendor of its kings was no legend. Babylon in its heyday was called “the wonder city of the ancient world.” It covered some 850 hectares larger than Nineveh to the North.

Archaeology illuminates much of the Bible even if indirectly.

Archaeology illuminates much of the Bible even if indirectly.Impregnable Babylon

Babylon was roughly square in shape, divided in half by the Euphrates River, very much part of our news today. It was a well-planned city with broad straight streets crossing one another at right angles, not unlike most cities today. Babylon was surrounded by double defensive walls which the ancient geographer Strabo estimated as one of the world’s Seven Wonders all on their own. The walls were moated and the Greek historian Herodotus was thought to be exaggerating when he reported the walls at more than 300 feet high and 85 feet thick – enough space for a four-horse chariot to turn around on. Yet researches in the 1800s largely confirmed these dimensions.

There were eight gates into ancient Babylon, and the Ishtar Gate – dedicated to the goddess of love – was the access route to the famous Processional Way. This splendid boulevard was the main north-south avenue of the city – more than 70 feet wide, paved with stone and flanked by carved lions. No wonder Koldeway’s discoveries were the talk of all Europe. Through Babylon’s portals paraded Nebuchadnezzar, Darius and Alexander the Great, and the captives Daniel and his friends – biblical characters one and all. In particular, Koldeway’s team excavated one of the most magnificent buildings ever raised on earth – the Royal Palace of Nebuchadnezzar. It was strategically positioned in the center of the northern wall with the Euphrates River on the west and a canal running in going south to southeast that served as a moat.

The German expedition measured the south walls of the throne room at 20 feet thick with three walls to the north and others further on measuring about 50 feet across. Amazing! The entire city was also protected by an Inner Wall consisting of two parallel walls of brick 20 feet thick, 40 feet apart, with the space between filled with rubble for a total breadth of 80 feet. The Outer Walls were on the same scale. Halley’s Bible Handbook concludes: “In the days of ancient warfare the city was simply impregnable.”

Yet Babylon fell? How and why? And what are the lessons for us today?

The Hanging Gardens?

Just to the west of the palace or royal residence lay the famous “Hanging Gardens” of Babylon, suppsoedly the site of the Garden of Eden. The story goes that Nebuchadnezzar built the hanging – actually terraced – gardens to please a young wife who, on the flat Mesopotamian plains, missed the cool mountains and forests of her native land.

At the northeast corner of the palace, the German expedition discovered an underground crypt consisting of a series of arched vaults with a wall nearby. Today’s view is that those vaults served as warehouse and administrative units, as lists of rations for Jewish exiles were found there. One of these ration lists mentions Jehoicahin of Judah, a king carried into captivity and given favored rations just as the Bible had recorded (2 Kings 25: 27-30). See J.B. Pritchard’s Ancient Near Eastern Texts, page 308.

Thus Great Babylon, an urban center for perhaps 100,000 to 200,000 people. No wonder Nebuchadnezzar called his palace “the marvel of mankind, the center of the land, the shining residence, the dwelling of majesty” (Joan Oates, Babylon; Jacquetta Hawkes, Atlas of Ancient Archaeology). And yet Babylon fell. According to the biblical book of Daniel its fate was decreed by the prophet Jeremiah: “Babylon will be captured; Bel will be put to shame and…her idols filled with terror…No one will live in it; both men and animals will flee away” (Jeremiah 50:2-3).

Bel and Marduk were two of the chief gods of Babylon.

But their gods could not save them. Now this ought to make us think.

Who is Lord?

Archaeology does not exist to “prove” the Bible but some of its discoveries shed light on the Biblical pages. Like the ancient Babylonians, we today can be very proud of our advances and scientific might. We can easily fall into the attitude of Nebuchadnezzar as described in Daniel 4:30, “Is not this the great Babylon I have built as the royal residence, by my mighty power and for the glory of my majesty?"

Babylon was great, perhaps the greatest city ever built to that time. But true greatness is not just measured in stone or steel. Affluence is not evil in itself and prosperity sure beats the alternative but we must never allow ourselves to get lulled into a false sense of security. Nebuchadnezzar, who considered himself “a little god,” was heir to the old Assyrian title, “King of Kings.” Yet his mighty walls are now ruins, not even shelter for the wild animals, mere material for the digger’s spade, precisely as the Bible had indicated (Jeremiah 50:2-3).

His great Ishtar Gate is now a museum piece. Nebuchadnezzar’s house, proud Babylon, lies in ruins. Christian look to Jesus, builder of a house not made by human hands, lasting eternally in the heavens (Hebrews 9:23-24). Archaeology can help remind us: The power and the glory are Christ’s alone, far surpassing every wonder this world can offer.

Neil Earle and his wife, Susan, met on an archaeological dig in the Middle East in 1970.