Grace With Gusto:

The Good News of Martin Luther

By Neil Earle

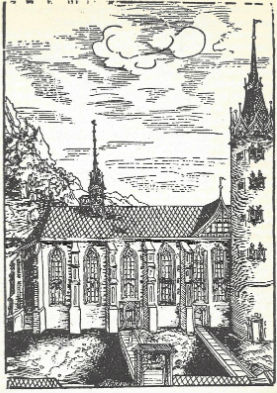

The Castle Church of Wittenberg. Here Luther posted his theses on October 31, 1517.

The Castle Church of Wittenberg. Here Luther posted his theses on October 31, 1517.October 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, an event still in play today.

Martin Luther (1483-1546) is considered the key figure in this religious revolution in Western Europe. Luther’s lasting influence, his dynamism, his personal complexities and the dark shadows cast by his obvious brilliance still engage the wise men of Christendom.

This article introduces Luther as a teacher possessed of a cheerful ability to not only proclaim Gospel grace and hope but to do it with a gusto and enthusiasm that perhaps only a son of North Germany could express. Luther’s happy enunciation of reconciliation between the Sinless One and sinners permeates his teaching but most pronounced, it seems, in his justly famous Commentary on Galatians. It’s a document more people outside the Christian church should read especially for those who feel lost, rejected, and hopelessly cut off from God.

The pious monk Martin Luther felt that way as well, as we shall see. We take our cue from Reformation expert Hans Hillerbrand who write: “Above all, Luther was an expositor of Scripture, and his commentaries on biblical books show him at his best” (The Protestant Reformation, page 87). Luther’s Commentary on Saint Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians in 1535 is heart-warming and revivifying for one thing: Master Martin’s at presenting a God as being on the side of the sinner.

“Passive Righteousness”

Luther the Professor begins with analysis. He observes that there are different kinds of righteousness.

There is political or judicial righteousness, which is well-known from the court systems.

There is ceremonial righteousness deriving from religious customs or traditions humans have concocted.

There is the day-to-day form of teaching obedience or familial obedience which parents must daily inculcate to their children.

Above all, there is even the righteousness expressed in the Old Testament Law of Moses, a Law, says Luther, containing many valuable things but now interpreted by Christians through the principle of faith.

This last becomes Luther’s specialty. This righteousness through faith he calls “this most excellent righteousness…which God imputes to us through Christ without works.” As Luther well knew, the Apostle Paul lived and died by this principle. Paul proclaimed his ultimate hope to be found “not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which is through faith in Christ – the righteousness that comes from God and is by faith” (Philippians 3:9).

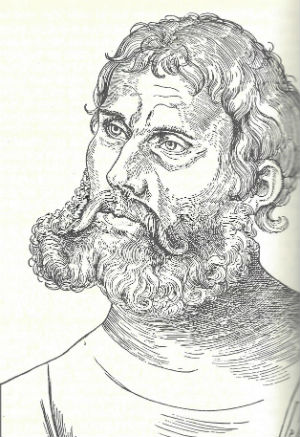

Luther's disguise in hiding while he translated the Bible into German.

Luther's disguise in hiding while he translated the Bible into German.It will be Luther’s exquisite delight to expound this in personal detail from Paul’s Letter to the Galatians. And he does this with force and passion and excellent German prose. This righteousness of faith which God imputes into repentant sinners by faith “is neither political nor ceremonial nor legal nor work-righteousness but is quite the opposite; it is a merely passive righteousness, while all the others listed above, are active.”

But isn’t being active a good thing?

Not in this matter of initial reconciliation with God, Luther insists. Our salvation begins and ends in Christ. When we have offended against our Creator it is unlikely that our damaged psyches will even know how to take the first steps in reconciliation. It is impossible for a worldly-minded sinner to please God (Romans 8:8). The gulf is too large. God Himself has to bridge it by a miracle of divine overshadowing by and eventual implantation of the Holy Spirit which conveys faith. Luther goes on:

“For here we work nothing, render nothing to God; we only receive and permit someone else to work in us, namely, God. Therefore it is appropriate to call the righteousness of faith or Christian righteousness ‘passive.’ This is a righteousness hidden in a mystery, which the world does not understand…Therefore it must always be taught and continually exercised. And anyone who does not grasp nor take hold of it in afflictions and terrors of conscience cannot stand. For there is no comfort of conscience so solid and certain as this passive righteousness.”

Luther’s Terrors

Luther himself had lived this excruciating dilemma of conscience. As an Augustinian monk he tried to live by every strict code of his order.

“Though I lived as a monk without reproach, I felt, with the most disturbed conscience imaginable, that I was a sinner before God” (Kittelson, Luther the Reformer, pages 87-88).

It was not till he saw clearly revealed in Scripture that God has to place this divine righteousness inside us by faith that he was fully delivered from a guilty conscience. “In other words this is the righteousness of Christ and of the Holy Spirit, which we do not perform but receive, which we do not have but accept, when God the Father grants it to us through Jesus Christ.”

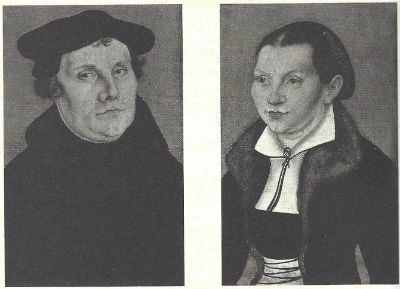

Martin Luther and his wife, Katharina von Bora, by Lukas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553).

Martin Luther and his wife, Katharina von Bora, by Lukas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553).This is so so eloquent – and encouraging to those who feel lost.

Luther explains how the poor sinner, confronted by a righteous God, groans within himself: “Oh, how damnably I have lived! If only I could live longer! Then I would amend my life.” Satan aggravates and increases these thoughts in us, says Luther and even the Law has a part in this. “For although the law is the best of all things in the world, it still cannot bring peace to a terrified conscience but makes it even sadder and drives it to despair. For by the law sin becomes exceedingly sinful (Romans 7:13).”

It’s as if sinners are caught in a terrible vise. There is only one way out. “I do not seek active righteousness,” says Luther, “I ought to have it and perform it; but I declare that even if I did have it and perform it, I cannot trust in it…Thus I put myself beyond all active righteousness, all righteousness of my own or of the divine law, and I embrace only that passive righteousness which is the grace, mercy, and the forgiveness of sins.”

We Can’t Earn It

This, says Luther, is something we can only obtain “through free imputation and indescribable gift of God.” Imputation could refer here to sprinkling, baptism, laying on of hands, a sincere response at a revival meeting or any way we have a conviction of coming to Christ. Christianity is a wonderfully flexible system. The key point is it is God who is doing it. Luther uses a clear analogy to explain this process:

“As the earth itself does not produce rain and is unable to acquire it by its own strength, worship, and power but receives it only by a heavenly gift from above, so this heavenly righteousness is given to us by God without our work or merit. As much as the dry earth of itself is able to accomplish in obtaining the right and blessed rain, that much can we men accomplish by our own strength and works to obtain that divine, heavenly, and eternal righteousness…Without any merit or work of our own, we must first be justified by Christian righteousness, which has nothing to do with the righteousness of the law or with earthly and active righteousness.”

Earthly righteousness – keeping within the speed limit, obeying the laws of parent and of the land – these are necessary on the human plane, says Luther. This is of the earth, earthy. But the righteousness that clears our conscience and reconciles us to God is a gift of the Holy Spirit. “We do not have it of ourselves; we receive it from heaven. We do not perform it; we accept it by faith, through which we ascend beyond all laws and works.”

This teaching of Luther can be powerful encouragement to people who think they have committed the unpardonable sin or stumbling sinners who wonder how God can ever forgive them “this time.” The good news of Martin Luther is that God imputes a forgiveness we could never work up for ourselves in a hundred lifetimes. This leads to Luther’s feeling about Christian hope and confidence we can address next time.