Ezekiel: Darkest Hours, Brightest Dawn

By Neil Earle

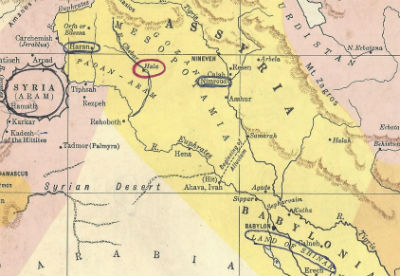

Assyria and other countries adjoining Canaan, illustrating the captivities of the Jews. Click map to enlarge.

Assyria and other countries adjoining Canaan, illustrating the captivities of the Jews. Click map to enlarge.Was the prophet Ezekiel the first Ufologist? Why did some Jewish groups insist his readers must be accompanied by a rabbi? Just casually reading him it’s not hard to understand why, but his marvelous message still excites us today.

Ezekiel is known as “the prophet of visions,” his book a “labyrinth of mysteries.” Few books have been so misunderstood and misinterpreted. His 48 chapters of fiery wheels, scrolls of woe, funeral dirges and piles of bones have been dismissed as – in the words of a sympathetic commentator – “All things wild and wonderful.”

Yet he is accepted into the Jewish canon as a prophet. The Gospel writers took Ezekiel’s familiar “son of man” and applied it to Jesus. It is in trying to understand what Ezekiel meant to people closer to his own time that we can more soundly relate to his hope-filled and dynamic message.

His book reapys close study but we do so with a firm priority to “decode” what his visions and parables and life experiences meant for people who first heard them.

An Audience of Refugees

Ezekiel wrote about 593-573 BCE. Few books are more consistently and repeatedly dated from the captivity of Jerusalem in 597 BCE (Ezekiel 1:2). His original audience was a community of Jewish exiles from Judah and Jerusalem carried into captivity by the fierce Babylonians over a period of decades. While no doubt still in shock from the traumatic experience of captivity, Ezekiel’s prophetic imagination began to soar in light of the visions and assignments Yahweh, the God of Israel, had laid out for him.

This is the vital backdrop to Ezekiel 1.

Ezekiel sorely needed the assurance that he had been called by Yahweh God himself. And did he ever get it: “In my thirtieth year, while I was among the exiles by the Kebar River the heavens were opened and I saw visions of god.” He tells us he himself was a 30-year-old son of a priest. At age 30 priests began to minister in the Jerusalem temple (Number 4:3), but Ezekiel was way-off in Babylon, modern-day Iraq.

Yet God was still calling him to minister. “There the hand of the Lord was upon him” (1:3).

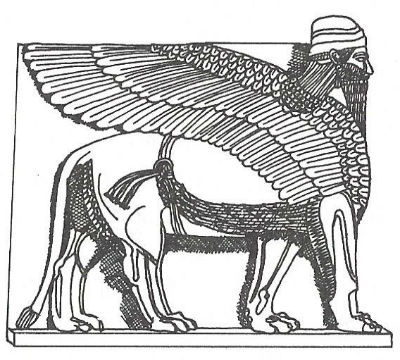

God gave him a vision of the cherubim, those angelic attendants on Israel’s God. (See picture.) So that encouraged early on the thought that God was not finished with Israel. Did the true God need a temple to carry out his purposes? Obviously not. The omnipresent God was still on the job and he could “show up” anywhere. This was part of Ezekiel’s hope-filled message. He paints for them a soaring vision of a powerfully transcendent planning an utterly more magnificent temple for true worshippers (Ezekiel 40-48).

But the people are dispirited, hard-headed and resentful. They still cling to the stubborn hope that sin-filled Jerusalem will yet hold out back there in Palestine. Ezekiel knows differently. For their foolish rebellions Jerusalem will eventually be flattened by the Babylonians just as God’s man in Jerusalem, the prophet Jeremiah was warning them. Young Ezekiel will have a hard time making progress with that mind-set, but his God was with him. His name told the story of his life – (from Chazak and El = “May God make me strong.”) Their heads were hard but God always equips his servant to persevere (Ezekiel 3:4-9) – another lesson from this book.

The Great Communicator

Ezekiel is perhaps the most colorful and vivid communicator among the prophets. His creative approaches to his messages were unexcelled.“Ezekiel uses almost every kind of literary device and imagery to communicate graphically the messages of judgment and blessing: dream visions (Chapters 1-3; 8-11); apocalyptic literature (37:1-14; 40-48); drama (4-5, 12); allegory, parable, proverbs (16:44, 18:2); and funeral dirges (19: 276-28; 32). The frequent rhetorical questions and repetitious phrases enhance the vitality and thrust of the oracles” (Expositors Commentary, Volume 6, page 745).

The Word Biblical Commentary expounds seven of his sign-visions ranging from the clay tablet and iron griddle of Ezekiel 4:1-3 to the Parable of the Bizarre Barber in Ezekiel 5:1-4. William H. Brownlees comments:

“He had a large repertoire…Symbolic pantomimes portrayed the coming doom (chapters 4-5; 12:1-7; 24:1-14) and the coming reunited nation (37:15-23). His vivid and colorful imagination found expression in poetry, especially in his allegories (chaps. 15-17; 19; 23:27). Many of his oracles were poetic and were probably chanted” (Word Commentary: Volume 28, page xxv).

Ezekiel illustrates very well Hebrews 1:1, how “God spoke through our forefathers in various ways.” His book is a literary treasure.

The Supra-Natural Visions

Ezekiel was among those deported in 604 BCE (2 Kings 24:16) and S. Fisch tells us that as late as the 1800s there was still a village near the ship canal off the Euphrates River known as “Kafir al-Kilfil” – Arabic for Ezekiel. Plates have been found inscribing Ezekiel’s 48 chapters and may indeed be genuine. God picked a talented Levite to record his words. He deftly sketches the Cherubim with four-faces and full of eye front and back. This depicted God’s omniscience, his ability to see all that was going on. The wheels signified God’s omnipresence, that quality allowing God to be everywhere at once.

Priests at Jerusalem saw the cherubim depicted on the temple veil Solomon had made. This encouraged Ezekiel greatly. God was still on the job. God was in charge of time and space. Geography and national boundaries meant nothing to him. Here is another of Ezekiel’s implied lessons. He has a very high view of the Godhead.

Ezekiel does struggle sometimes to express in human language his sense of the divine presence. Stuart Briscoe says, “He was trying to describe a vision of God which incorporated many of his divine attributes with words that were incapable of conveying the real meaning…It was as if he had heard Beethoven for the first time…and then tried to play the composer’s Fifth Symphony on a tin whistle.”

For example Ezekiel 1:18 reads literally in Hebrew, “As to their rims, height to them and fear to them.”

So the prophets make it clear that God in His glory cannot be captured by human words and creations, as St. Paul would later tell the Greeks (Acts 17:29). This is one reason God came in the flesh to give us the fullest revelation of what God is like in the person Christians know as Jesus Christ.

Ezekiel 3:10-15 he begins. He is taken by the Spirit and plopped down among a group of the captives. He sits there seven days “overwhelmed” – perhaps still dealing with the after-effects of the vision or wondering how to proceed. He knows that for those who hold out forlorn hope that God will spare Jerusalem there is worse news ahead. Jerusalem is still hanging on by a thread. The events in Ezekiel 24:1-2, 26-27 report the final siege of Jerusalem when the temple falls and all physical hopes seem dashed.

Indeed, Chapter 24 is a pivot in the book. It neatly divides Ezekiel’s 48 chapters and his ministry. In trying to point the hard-headed captives to a new Temple, a New Jerusalem, a New Heart and Spirit, Ezekiel has met resistance. He’s had to be a bad news bringer. But deep down he knows that, with God, disappointments are His Appointments. Surprisingly, after Jerusalem’s final death agony in 586 BCE Ezekiel begins to turn optimistic and hopeful. He shows the refugees that the darkest hour is before dawn. Almost unbelievably he teaches they will return to the land and there will be a new temple, new land, new priesthood and a new covenant.

Ezekiel had gone through great lengths to show Jerusalem’s doom. He made tiny building models, he pantomimed captives burrowing under the foundations to escape, and he ate starvation rations (Ezekiel 4). In Ezekiel 10 he showed God’s glory symbolically departing from the temple. This is as bad as it gets for an Israelite. Yet in the midst of it all Ezekiel begins to hammer out hope. The whole purpose of their national punishment is wrapped up in his recurring phrase “they shall know that I am the Lord.”

Thus there are streaks of grace amid the overtones of judgment. When the nation learns its lesson it will be given a new heart and a new spirit (Ezekiel 11:17). Thus Ezekiel becomes the prophet of the New Covenant, like Jeremiah before him (Jeremiah 31:31). No wonder the Christian church has preserved and treasured their messages.

A International Witness

After describing Jerusalem’s sinful escapades and depicting the fall of the city, Ezekiel now begins to speak against the hostile nations who have been a thorn in Jerusalem’s side. Judah’s neighbors – Ammon, Moab, Edom and Philistia – are singled out in Ezekiel 25. Ezekiel 26-28 and 29-32 are blocks of beautifully descriptive prophecies against two of the great powers of the time – Tyre, base of the mighty Phoenician Empire and haughty Egypt. Mt. Seir and Edom are rebuked again in Chapter 36 because Edom is Israel’s brother and should know better.

Then – a great reversal.

New Heart and New Spirit

In the midst of this searing series of oracles, Ezekiel is recommissioned. Judah has fallen, Babylon has leveled Jerusalem, the Jews are in bitter captivity, but…this does not mean God has forgotten his people. Optimism begins to surcharge the narrative. Ezekiel is told to be a Watchman to pass on God’s words to the nation and prepare for national renewal.

“God will rebuild Jerusalem,” Ezekiel begins to say. Once again he reminds the people of Yahweh’s offer of a new heart and a new spirit to a newly restored nation. This promise sets the stage for the impressive Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones (Ezekiel 37). Though this chapter has overtones of future resurrection for Christians, the original message is clear: The nation will live again. Babylon, that great graveyard of nations, will not overturn God’s plans for his people. “For I will take you out of the nations; I will gather you from all the countries and bring you into your own and. I will sprinkle clean water upon you and you will be clean. I will cleanse you from all your impurities and from all your idols…And I will put my Spirit in you and move you to follow my decrees…” (36:24-27).

Though this is fulfilled especially in the Christian church with the coming of Jesus and the apostles, the lesson for Ezekiel’s audience is clear – Israel will live again. They still do!

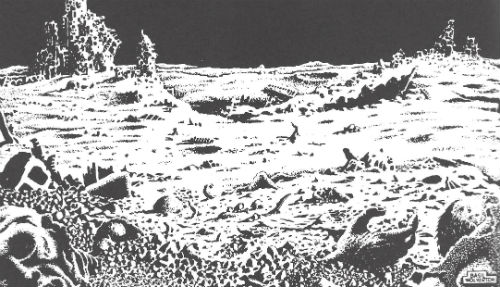

Can these bones live? God's question refers to national Israel and hints at the resurrection to come. Basil Wolverton artwork

Can these bones live? God's question refers to national Israel and hints at the resurrection to come. Basil Wolverton artwork

The Messianic Age

“The prophets were amazingly well-informed,” says Professor Paul Dionne of the University of Toronto. That is shown in Ezekiel’s minute description of mighty Tyre as an intricately formed but doomed ship sailing to destruction. Likewise the mysterious chapters relating to Gog in Ezekiel 38-39. Some see a hyperbolic “dream vision” of powerful King Gyges of Lydia (in modern-day Turkey) who is imaginatively reconceived as the best candidate for Ezekiel’s Gog. But mainly the late appearance of Magog, Tubal and Meshech to the far north – nations seen as far from the Holy Land – coming to finally know the Lord after their shattering defeat (38:23), this very much fits the overall theme of the book.

The whole sequence fits the dream vision style of prophecy, a mixture of historical reality and vision. Gog’s army swooping down on a defenseless Israel and God’s shattering intervention forcing seven months to bury the casualties is close to the “apocalyptic” style of writing. In apocalyptic, seen in books such as Daniel and Revelation, etc. the technique is to drive home one simple point by exaggeration, not exaggeration for purposes of distortion but to make the lesson unforgettable.

Apocalyptic takes us from a silent black and white movie to brilliant Technicolor. The lesson here – which fits the end of the book – is that Yahweh will be the guarantor of Israel’s security. The vision seems to fit what many call the Messianic Age (Anchor Bible Dictionary, Volume 2, page 1056) but even here the theme of peace and security is all.

This is perhaps why Ezekiel’s temple vision fits no structure Israel or any other nation has built. As L. John McGregor teaches, “it is a mixture of the ideal and the real” – not supernatural but SUPRA-natural meaning beyond this time and space. The marvelous vision of the Healing Waters flowing from the new temple in Ezekiel 47 is in that vein. Jesus applied this to himself in John 7:38. So with these last chapters we are in a different world, it seems, one many Jewish and Christian commentators know as the Messianic or Kingdom Age, a pointer to God’s restoring his rulership over the earth, already begun, teach Christians, with Jesus’ earthly ministry.

How literally we are intended to take such visions is debated to this day. What comes across clearly is the promise of God’s sovereignty guaranteeing the future security of all those who turn to him and receive a new heart and a new Spirit. Ezekiel’s last words are “Yahweh Shammah” – “the Lord is there” and many Christians see this vision complementing the end of the book of Revelation where the nations co-exist in peace in a New Heaven and a New Earth, a vision beyond anything our earth-bound minds can conceive.

All of which makes Ezekiel’s writings a tomorrow book!