1917 – ‘America Enters the War:’ Seventy Years Later

By Neil Earle

America entered WW1 in 1917 with high hopes for the future. Though wars did not cease, America's participation changed this nation forever. How? Historian Neil Earle leads this intriguing discussion at Duarte Library, Saturday, April 8, 1PM.

America entered WW1 in 1917 with high hopes for the future. Though wars did not cease, America's participation changed this nation forever. How? Historian Neil Earle leads this intriguing discussion at Duarte Library, Saturday, April 8, 1PM.“The First World War (1914-1918) changed everything,” writes British historian Niall Ferguson of Harvard. The effects of what Europeans call “The Great War” which America entered in April, 1917 – 100 years ago this spring – changed the country forever.

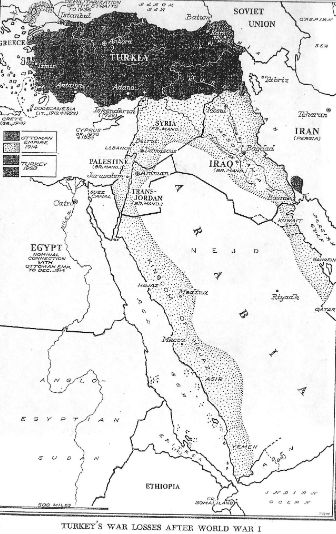

Fallout from that hitherto unprecedented clash of nations is with us still, most notable this spring in fighting in the heart of the Middle East in places such as Syria and Iraq, nations carved from the corpse of the old Ottoman Empire. “Disillusion” was American historian’s Barbara Tuchman’s one-word summary in her 1962 prize-winning The Guns of August, about a war often billed as “the war to end war.” But can we learn from history? President John F. Kennedy allegedly presented to his staff Tuchman’s masterful piece of history to avoid the “trap” of war by lock-step inevitability.

“The Game of Nations”

One of the enduring lessons of 1914 was that the Great Powers must not be drawn into third party conflicts, why most of our conflicts since the middle of the 20th Century have been limited. I remember telling one anxious young student of mine the week of the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, “This is limited war. Great powers are not facing off against one another with all they have. Thank the Lord for that.”

Today's borders in Syria and Iraq directly stem from the Paris Peace Settlement of 1919.

Today's borders in Syria and Iraq directly stem from the Paris Peace Settlement of 1919.

Still, well-remembered slaughters (at least in Europe) as the French army losing 50,000 men to gain 500 yards of territory in Champagne were still in our 1960s textbooks. A million Frenchmen and Germans eventually died in the struggle over the frontier fort at Verdun. These losses shook France to her foundations. In some ways she never has recovered.

Momentous too was the aftermath, the way the Second World War grew out of the First: Germany’s wounded pride, American disillusionment with “the war to end wars,” Anglo-French determination to remain empires no matter what, keeping the “game of nations” alive.

A brilliant French journalist had sketched the causes of the war with admirable compression. “The growing tension centered about three principal difficulties,” Raymond Aron summarized in The Century of Total War, ”the rivalry between Austria and Russia in the Balkans, the Franco-German conflict over Morocco, and the arms race – on sea between Britain and Germany, and on land between all the powers. The two last causes had produced the situation; the first one kindled the spark” (page 16).

Any way we slice it the consequences of World War One were huge.

Another big cause was President Wilson's desire to shape the peace settlement in a more humane, effective way.

Another big cause was President Wilson's desire to shape the peace settlement in a more humane, effective way.War and Consequences

First, a “lost generation.” Europe suffered the death of millions of men in what seemed a lost cause. Civil war convulsed the new Soviet Union and an influenza epidemic in 1918-1919 killed 40 million around the world. All this in spite of genuine heroics such as Sergeant Alvin York capturing 132 prisoners in 1918, saving hundreds of lives.

Still, most felt that the war had solved nothing and only unleashed new problems. A hard new cynicism gripped many people, evoked in the United States in the novels of Ernest Hemingway. The war saw a noticeable backlash against conventional morality and mores. “GOTT MIT UNS” was the now cruel-seeming slogan caved on the belt buckles of many German soldiers marching off to war a hundred years ago. In 1914, pastors and priests egged on their young congregants with blithe assurances that God was on the side of the nationality to which they belonged. The mood of let-down played havoc with the claims of those representing the Prince of Peace. The backlash against churchly participation in a war that took nearly ten million lives, including two million Germans, still lingers, especially in Europe. Most of the great Medieval cathedrals are almost empty each Sunday.

The new, somewhat disturbing ideas of Sigmund Freud now seemed superior to the sermons being preached on Sunday. Albert Einstein’s thoughts on “relativity” began to enter the 20th Century lexicon as an excuse for “anything goes,” the title of a Cole Porter song. A leveling trend was in vogue, moving millions from their hitherto reliance on authority. American women made some important gains, getting the vote in 1920. This would eventually prove one of the biggest changes of all. Labor unions also emerged as strong forces shaping 20th Century America.

The Ottoman Empire collapsed in WW1 and led to the modern borders of the Middle East. Click to enlarge.

The Ottoman Empire collapsed in WW1 and led to the modern borders of the Middle East. Click to enlarge.“On the Other Hand…”

All these events were deep and real shocks to the fragile assumptions of the 1914 world. This partly explains the tendency to write off WW1 as a totally unredeemed failure, especially the peace treaties at Versailles that ended the war. Yet Barbara Tuchman and another lady historian, Margaret Macmillan. Civilized norms still held fast overall in spite of the horrors and dehumanization of trench warfare. The world still abhors poison gas attacks, for example. German and British troops did mingle in No-Man’s–Land that first Christmas of the war and Germany later surrendered on honorable terms that emanated from the American President Woodrow Wilson. Those terms enshrined in the famous Fourteen Points probably shortened the war from being an even more pointless fight to the finish. MacMillan argues in her provocative account Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World that the efforts of those sincerely committed to a just peace with Germany at the Versailles Conference in 1919 were “not completely wasted.”

In the end Germany was not dismembered as some wanted. It was not a “Carthaginian peace” as the American biographer of Woodrow Wilson, Arthur Link, tried to remind his generation.

“A New Spirit”

Peace conferences often have fatal blind spots but MacMillan argues for a new spirit abroad after 1919. Somehow nations and national grouping and their leaders were going to be held more accountable, there was a sense of a moral order operating even among nations. Some standards could be stretched and sometimes subverted for a while but never completely overthrown. Consider the world-wide revulsion against Weapons of Mass Destruction and civilian casualties, for example. “Hitler did not wage war because of the Treaty of Versailles,” MacMillan argues, though it gave him an excellent straw man for his propaganda. “He would have demanded…the destruction of his enemies, whether Jews or Bolshevik. There was nothing in the Treaty of Versailles about that.”

Even Barbara Tuchman for all her stress on “disillusionment” was struck by the human attributes of hope and resilience that may afford us today a slightly altered view. She wrote: “Men could not sustain a war of such magnitude and pain without hope – the hope that its very enormity would ensure that it could never happen again.” That hope may not have been fulfilled, but she then adds how “the mirage of a better world glimmered beyond the shell-pitted wastes and leafless stumps…the hope that out of it all some good would accrue to mankind kept men and nations fighting” (pages 439-440).

In far-off Labrador, John Shiwak, an Inuit trapper, turned into an excellent scout for his regiment, “fought and died alongside ‘corner boys’ of St. John’s.” The Labrador volunteers had paid the price, he said, so that “their capital city wouldn’t lord it over them in quite the same way” (As Near to Heaven by Sea, page 334). A great leveling was indeed at hand, though delayed in many quarters.

Perhaps all this is another way of saying that (without descending into hopeless optimism) we seem to be a resilient and determined species. The League of Nations came directly out of the Great War and out of its failure came, indirectly, World War Two but also the United Nations, keeping alive a sense, however obscured, of global values and norms. American leaders learned the lessons of World War One and ensured the headquarters would sit in New York City so that the greatest world power would be tied to wider goals and purposes. A lesson bitterly learnt!

“The United Nations,” Winston Churchill once said, “was not designed to lift us to heaven but to save us from hell.”

The searing let-down of World War One had shown, as well, how almost fatally peace-loving democracies could be mobilized in defence of civilized values. Men named Truman, Patton, MacArthur lived to fight and rebuild the next generation. It may be more possible with the passage of time to lend some “dignity and sense,” in Tuchman’s words, to the sacrifices that the guns of August, 1914 called forth. The many monuments that dot small-town North America show that remembrance is not yet out of fashion.

(Neil Earle teaches history at Grace Communion Seminary in Los Angeles.)