A Rugged Spirituality: Psalm 42/43

By Neil Earle

Today the subject of Spiritual Searching can encompass a lot of territory (literally!)

Today the subject of Spiritual Searching can encompass a lot of territory (literally!)Spirituality has been defined as a loss of the sense of Self in the encounter with Something More – a “reaching out to super-sensible realities,” the capacity for going out of oneself and beyond oneself in moments of transcendence.1 These definitions, however, equally apply to the kind of generalized soft-focused mysticism much in vogue today. Christian critics warn that these definitions which work outside the Christian experience should give us pause. Hence the title of a J.I. Packer book of the 1970s: Hot Tub Religion. Sandra M. Schneiders defines Christian spirituality more formally as the capacity for transcending the Self activated by the particular, specific gift of the Holy Spirit. This results in a “a life-giving relationship with God in Christ within the believing community.”2 This comment is certainly Christian as far as it goes, but it could also be skated over to describe as merely banal as church attendance, and it is just this very hungering for something more than “mere” church services that has triggered the present upsurge of interest in the spiritual life.3

What is always needed, if not appreciated, is a sound, thorough, biblically-based approach to spirituality. This paper seeks to show that the blunt and forthright admission of God’s absence in Psalms 42/43, together with the reinforcing linguistic and rhetorical devices employed to dramatize that crisis, grounds a realistic, sturdy, Biblical-based spirituality. It accepts the totality of God’s working with us, in season and out of season. Christian spirituality, if it is to be comprehensive, must take account of something not often spoken about in today’s tapes, seminars and retreats: the sense of God’s absence. The Psalms, with their capacity to present us with every emotion with which the minds of men and women are wont to be engaged, to quote John Calvin, ground us in both Scriptural and experiential realities.4 The Self as Seeker, a dominant motif today, is clearly present in Psalms 42/43, but it is a Self engaged in the real world, the world of hellos and goodbyes, of sweetness and darkness, of presence and absence. The crisis that triggers the anguished and panicky reflection is a very painful alienation from the temple/tabernacle service: “I remember how I used to go with the multitude, heading the procession to the house of God, with shouts of joy and thanksgiving among the festive throng” (Psalm 42:4). Now he is cut off from the rites of the Jerusalem temple and stranded, possibly in the northern Hermon region of Israel, far, far from temple service.

In our terms: he misses church.

His words reflect an existential longing that speaks to us across the centuries. There is a sense of pathos and grief that is unmistakable. “My soul is downcast within me…all your waves and breakers have swept over me” (v. 5-6). However, the object of his yearning is not to “get in touch with his own emotions” but the throbbing need to meet with God, even more, to meet with God in the presence of others.

Christian spirituality has been succinctly defined, once again, as the integration of theology with real human life. Sound Christian spirituality builds upon the precedents of the past. In Psalms 42, 43 the student of spirituality is particularly fortunate. His poem abounds in the similes, metaphors and word pictures (“thirsty deer,” “tears as food,” warm and enveloping light, praises upon the harp, and three-fold repetition) – rich and enduring poetry that trace from a mind accustomed to match heart language with head language. Thus the inner yearnings and spiritual reaching out to something or Someone greater, preserved and powerfully conveyed across the centuries by the effective use of literary tools, offer guidelines by which to evaluate spirituality, ancient and modern. This is not William Wordsworth’s “emotion recollected in tranquility” as much as emotions recollected in crisis, a presentation pointing ahead to the undergirding hope of embracing a higher presence.

The rhetorical structures give force to the reflections of a soul sensing its exile and stabbing loneliness. The typical psalm-speak exemplified in these two songs, combats the tendency to abstraction and clouded solipsism that often characterizes too many expressions of spirituality in our day. The intellectual rigor we bring to untangling the often concrete and vivid metaphors and allusions involved has the capacity to involve us at a deeper level un the poet’s words and, in Barbara Green’s words, change us in some way.5 The Psalms live on. The present popularity of “As the Deer” as a contemporary anthem, at least in evangelical circles, is eloquent evidence. The measured use of figurative language is part of the reason why and needs attention.

David’s psalms are like roses in the desolate Wilderness of Judaea where he wrote many of them.

David’s psalms are like roses in the desolate Wilderness of Judaea where he wrote many of them.“Ad Fontes:” or To the Text

First, we will need to construct a workable translation of Psalms 41/42 and identify genre and structure. The bulk of the paper will then proceed, commentary-like, to examine individual words and phrases, to explain word play and syntax – those literary devices that support and add to the weighty insights contained therein. A summary spiritual reflection – answering the question of how these psalms help us approach deeply-rooted spirituality – will lead to a conclusion on how the choices of language employed help make the spiritual message accessible to readers in our day.

It is good to begin with the text, to gain an overview first from different translations. Three basic English translations have been consulted, each with their distinctive stress and emphasis. The Tanakh begins very forcefully and compressed as indicated in the opening trope, “Like a hind crying for water.” The New International Version (NIV) strives hard to be forceful but contemporary: “As the deer pants for streams of water/so my soul pants for you, O God.” Yet the word “pants” has a mildly pejorative overtone for modern readers. It is a hard “p” word. Distracting. Much better is the flowing and more generous phraseology of the New Revised Standard Version’s (NRSV) “as a deer longs for flowing streams/so my soul longs for you, O God.” The wistful and emotive “longs for” seems to capture the note of exile and disorientation that appears in the rest of the stanza. Similarly, Tanakh’s “I am ever taunted with” is too artful and artificial-sounding to bear comparison with the NRSV’s more colloquial “while people say to me continually.” Yet, here, the NIV’s “while men say to me all day long, ‘Where is your God,’” is an advance on both.

The phrase “all day long” conveys to English readers a sense of weariness and desolation appropriate to the mood of a devout worshipper cut off from the tabernacle service and in the presence of Tennyson’s “people who feed and eat and know not me.” Both NIV and NRSV agree on the sonorous “These things I remember, as I pour out my soul” which seems much statelier than Tanakh’s clipped “when I think of this, I pour out my soul.”

Approaching what is a repeated refrain (Psalm 42:5, 11; 43:5) NRSV also continues the AV rendering of “Why are you cast down, O my soul?” – a rendering more accurate and more fitting than the NIV and Tanakh versions. A “cast down” sheep, if Philip Keller is to be believed, was a technical Old English term for a sheep that had wandered into a pit and too encumbered by its wooly covering to get up on its feet.6 This insight adds weight to the choice of words in NRSV’s rendering of Psalm 43:3. The NRSV also preserves the AV line of translation by prefixing the exclamatory “O!” before the line translated starkly in NIV and Tanakh – “send out your light and your truth.” The NRSV here conveys the emotive force and the sense of desperate appeal that flows through many of these psalms. Finally, the concluding apostrophe to God is rendered differently in these three basic versions. The NIV sounds evangelical: “My Savior and my God.” Tanakh is creative and bold: “My ever-present help, my God.” NRSV has the simplicity of brevity which seems more apt: “My help and my God.”

This basic textual comparison lays the groundwork for a personal translation of Psalms 42, 43.

An Exile’s Lament: Part One, by Neil Earle

Psalm 42: Just like a hunted deer is desperate for water, so my soul is desperate, so desperate for you, my God;

Everything inside of me cries out for the presence of God, for the living God.

When will I once again be able to see the face of God?

I’ve had to drink my tears as food while my critics say, “Come on, where is your God now?”

As I pour out my soul before you, I am oppressed by beautiful memories of seeking you in the temple, keeping a festive occasion with huge crowds…

Why is it I feel like this, so forlorn and forsaken?

Whence comes this gnawing emptiness within?

Hope – I say to myself – hope still in God; I will yet praise my Helper, my God.

But my anxious thoughts return – I am cast down.

When I think of the heights of Jordan and snow-capped Mount Herman, Mount Miser,

All I can thank of is those swollen mountain rivers cascading down on my head…

But wait, God still loves me. Yes, why else would something within me want to sing in the night, to pray to the God who has led me safe thus far.

Yet…I have to ask my God, My Rock – Why have you forgotten me? Why must I sneak and scurry around because of the oppression of my enemy?

Their taunts and jeers have sunk in like deadly wounds – Where is your God, they say!

So I ask again, almost to my own surprise: Why are you cast down, O my soul? Why do I feel such awful anguish within?

Enough of this: Trust in God.

I am sure of this: I will yet have cause to praise him, my Help, my God.

Part Two: Psalm 43

Justify me, O God and defend my cause against a people who do not care for you at all.

From the deceitful and wickedly unfair, rescue me.

For you are the God in whom I habitually take refuge – why are you casting me off this time? Why is it that I am walking around in mournful desolation because of the oppression of the enemy?

I am really pleading with you God – I beg you: Please send out your light and truth and quickly. Let them lead me. Let them bring me to your holy hill, to the place you choose to dwell. Then I will go to your altar, to God my choicest joy. I will praise you with the harp, O God, my God.

Why am I so discouraged? Why so upset within? Hope in God alone. I will yet live to praise him, my Help and my God.

The Lament Mode

As to literary genre, a host of commentaries agree that this is an individual lament, though streaked with strong elements of petition from an individual cut off from communal worship.7 The lament mode also features notes of complaint which explain the interrogatives in verse 2: “Why have you rejected me? Why do I go about mourning?” This clouded hope ends with the resolution of 43:4-5. Peter Craigie argues that some have interpreted Psalm 42/43 as a national lament, taking the “I” to represent the nation, or even as a royal lament, dealing with the plight of King David on one of his dangerous escapades of escape from Saul or Absalom. Yet the indication of a clear specific setting in northern Israel argues against this point.

Some propose that this anonymous lament fits the intense longing of the Babylonian Exile when the Temple lay desolate or, perhaps, a time of personal illness. Yet the specificity of Psalm 139, for example, “by the waters of Babylon,” is lacking.8 What we find instead is an allusion to snow-capped Mount Hermon in northern Israel. The exact location of Mount Mizar is unclear. So a location in northern Israel seems most likely by default. This renders more poignant the soliloquy mode of Psalm 42, the Soul communing with its own misery. “I say to God, my Rock, ‘Why have you forgotten me? Why must I walkabout mournfully because the enemy oppresses me?’ (Psalm 42:9). The twice-repeated introspective soliloquy “Why are you cast down, O my soul?” heightens the poignancy of the lament and the note of bitter near- hopelessness.

Scholars asks: Is anything more important?

Scholars asks: Is anything more important?The Nefesh Refrain

In an important insight, Bernhard Anderson notes that Psalm 42/43 opens what Psalm-scholars know as “the Elohistic Psalter” (Psalm 42-83). In these songs, the general name of Elohim (God) has replaced the specific covenantal name, Yahweh.9 This makes the lament an even more open-ended missive: any human being, not just covenant people, can identify with the spiritual frustration evoked. The Elohistic emphasis is also seen in the structural outline of 42/43 where the word “soul” is so prominent. As James Luther Mays says: “The soul cannot survive without God. That is true of every human soul, not just the deeply pious.”10 This will be explained below. Both songs can be outlined around the thrice-repeated “nephesh” refrain “Why are you cast down, O my soul” (Psalm 42:5, 11; 43:5), which again recalls Genesis 2:7, “and man became a living soul” – Genesis, the Book of Beginnings in the Hebrew oeuvre, for all humankind.

The tight linguistic framework as, for example, revolving around has led many commentators over the years to treat them as one song. A three-fold structure can be deduced from the three-fold pathetic outcry:

Opening – Psalm 42:1

Individual Lament – 42:2-4

Refrain – 42:5

Lament/Complaint – 42:6-10

Refrain – 42:11

Prayer: Petition for Vindication – 43:1-4

Refrain – 43:5

Even in English use today we have the proverb: “Repetition is the strongest form of emphasis.” The threefold refrain “Why are you cast down, O my soul “unifies the two psalms as well as setting up some interesting distinctions. Whereas the refrain of 41:5 comes at the end of a section where the poet’s remembrance is nostalgically focussed on missing the experience of crowds joyfully keeping festival at the tabernacle or temple, the refrain of 42:11 sets up Psalm 43’s strong prayer of petition for vindication. This prayer reaches a kind of crescendo in the beautiful, heartfelt request for God to send out his light and truth from his holy hill of Zion.

Overall, the two psalms are held together by the dynamic of Worship Lost/Worship Desired/ Worship Promised. There is an energy in this threefold rhetorical underpinning that lends strength to the hard-won resolution: “I will indeed go to the altar of God, to God my exceeding joy.” The word “joy” is significant. It is a hard-won note of optimism of one hoping against hope for a successful resolution to the crisis of alienation. Tracing the rhetorical and syntactical strategies behind this hope of resolution is our next task.

The subject of the Soul is more complex with today’s knowledge explosion.

The subject of the Soul is more complex with today’s knowledge explosion.“Deep calls to Deep”

This section-by-section analysis of Psalms 42/43 seems called for by the text since Psalm 42:1-5 is a clearly demarcated first section. The refrain “Why are you cast down, O my soul?” ends this passage, which flows smoothly, from the elegant opening simile (“as the deer”) to the heartfelt cries: “My soul thirsts for God,” “My tears have been my food,” “I pour out my soul.” The Hebrew transliteration for soul, “nefesh,” underscores the atmosphere of personal peril and frailty and the searching inward communion that forms the emotional nexus of this opening section. Why is this? Simply because the existential loneliness explains Gunkel’s reference to the “heartfelt notes” struck by the psalm.11 The repetitive use of nefesh injects another kind of syntactical energy that is very important. Verse 1 says “my soul longs,” verse 2 adds “my soul thirsts” and verse 4 addresses the soul directly in an apostrophe: “Why are you cast down, O my soul.”

As noted above, the second section springboards off this repetitive device with the flattened declarative: “My soul is cast down within me” (verse 6). At least in this first section, three of the key words appear to be “soul,” “face of God,” and “cast down.” These phrases are worth further exploration. As noted above, this passionate petition to “the living God” sets up echoes from the creation account in Genesis: “and the Lord God breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being.”

The Hebrew nefesh was the very living, breathing, personal part of men and women – what made “you, you,” we might say today. “The nefesh of Johnathan was bound to the nefesh of David and Johnathan loved him as his own nefhesh” eloquently declares 1 Samuel 18:1. The notion of a human being, a living nefesh, being chased and hounded to within an inch of her life by harrying enemies, this rich word portrait is accentuated by the nefesh references throughout 42:1-6. The sense of being at bay is vividly brought home by repetition here because, according to Hans Walter Wolff, the word nefesh “points preeminently to needy man, who aspires to life.”

This is not a shallow comment for, as we have seen, the concept leavens all of Psalms 42/43. Indeed “soul” is mentioned seven times. The broader meaning of nefesh as the individual “eager for life, spurred on by vital desire,” what Wolff again calls “needy man.” The semantic connection is tied to the word “vitality,” a point that illustrates the emotional depth involved in the thrice-repeated “why are you cast down, O my soul?” Wolff sees this very dire element of special pleading as important. “Here nefesh is the self of the needy life, thirsting with desire.”12 This helps make sense of the emotional power coiled up inside Psalm 42, beginning with a thirsty, needy nefesh, and the pausing at the end of section one to commune with one’s own innermost being: “Why are you cast down, O my soul?”

Moses as Seeker: The robust man of God sought Gods face on Sinai. Basil Wolverton artwork

Moses as Seeker: The robust man of God sought Gods face on Sinai. Basil Wolverton artworkMissing God’s Face

The second measure (cola) of Psalm 42:2 introduces one of the major themes of the poem: the sense of being cut off from God. “When shall I come and behold the face of God?” asks the psalmist. The face of God was an important concept in Hebrew life and theology. Jacob cried out, “I have seen God face to face!” (Genesis 32:30). Moses was supposed to have seen God face to face (Exodus 33:11). The face was a way of referring to God’s “presence” or his person generally. The word here is transliterated as panay from the Hebrew and is a masculine noun that referred to the intimate union of personal relationship. Psalm 16:11 says, “in your presence there is fullness of joy.” Psalm 140:13 says, “the upright shall live in your presence.” John Goldingay notes that the end of this section in Psalm 42:6 has been rendered more literally in some translations as “I will praise him for the salvation of his countenance.”13 When Yahweh’s face shone upon his people, they were blessed above all (Psalms 80:3, 7, 19). The Anchor Bible renders it in transliteration as yeshuot panay welohay, which helps explain the translation Savior used in the NIV’s Psalm 42:5 (“Yeshuot” coming from “Yeshua” or Savior).14 What is important here is that the extended notion of God’s face or presence radiating from 42:2 makes a subtle envelope pattern to close this first section.

What, then, of the “cast down” concept? This repeats in the second section, Psalm 42:6-11 and can be handled below in its turn below. Verses 6 to 11 plunge us into the rugged metaphors built around mountains, cataracts and rushing streams. Psalm 42:1-6 had put the poet’s enemies in the forefront. Psalm 42:6-11 boldly puts God in the dock. It is a passage depicting God as joining the persecutors. “All your waves and your billows have gone over me,” “Why have you forgotten me?” “My adversaries say…Where is your God?” This is, as we say today, really laying it on the line with God. The sense of desperation is accentuated by the poetic descriptions of waves and billows. Nothing is more disorienting than being tossed in a watery whirlpool, as this writer remembers from an experience on a youth camping trip in the Rockies in 1979. The sense of being sucked under by a corkscrewing riptide will stay with me forever. The worst feelings of helplessness struck me for an instant but then faith revived in a split second as I thought of my lovely wife, Susan, upstream fishing contentedly and something told me, “The worst will not happen.” Yet I have treated raging water and calm water with much respect ever since.

The Hebrews half-feared the sea. Their most notable mariner was Jonah! Out of the sea Daniel saw the four great beasts arise (Daniel 7:1-3). It haunted their dreams. This Hebrew allusiveness evoked powerful and emotive thoughts. The sea was freighted with references to the primal chaos where everything was tohuwabohu when “darkness covered the face of the deep” (Genesis 1:1-2). Over and over again in Israel’s national, patriotic songs deliverance from the Great Deep emerged as a constant theme. There is the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15:1-10. There is the reference to the “torrent Kishon” in the victory of Deborah and Barak, “the onrushing torrent, the torrent Kishon” (Judges 5:21). Psalm 18 resonates with that dramatic imagery: to be a servant of God was to be rescued from the overwhelming flood of troubles. “He reached down from on high, he took me; he drew me out of mighty waters. He delivered me from my strong enemy…He brought me out into a broad place; he delivered me” (Psalm l8:16, 19).

These powerful, emotive poetic allusions are followed by three interrogatives in verses 9 and 10. They are structured so as to have maximum shock value and they have a built-in crescendo effect. First the psalmist asks two questions about why he is forsaken. Then comes the Elijah-like bold challenge to God himself: “Even my adversaries are saying, where are you God?” There is an intensity and directness in this challenge to God and the syntax once again betrays the turmoil underneath. As one example there is the logical thought break between verses 7 and 8. “All your waves and billows have gone over me” which is followed immediately by the declarative “by day the Lord commands his steadfast love.” This sounds contradictory to our Western ears. What is happening?

“Block Logic”

Psalm 42:7-8 offers a chance to discourse on what is called block logic, a concept that helps make sense of much Old Testament writing. What does this mean?

[T]he Hebrews often made use of block logic. That is, concepts were expressed in self-contained units or blocks of thought. These blocks did not fit together in any obviously relational or harmonious pattern, particularly when one block represented the human perspective on truth and the other represented the divine. This way of thinking created a propensity for paradox, antimony, or apparent contradiction, as one block stood in tension – and often illogical relation – to the other. …In sum, the Hebrew mind could handle this dynamic tension of the language of paradox, confident that…mystery and apparent contradiction are often signs of the divine.15

Juxtaposing contradictory thoughts is somewhat anathema to our Western scientific mindset but to the psalmist it was a way of indirectly alluding to the mystery of life, the mystery of God. The seeming contradictions called more crisp attention to the passage. This fits the daring emotional pirouette of verses 7 and 8. “Deep calls to deep at the thunder of your cataracts”/“at night his song is with me, prayer to the God of my life.” In the words of James Luther Mays: “One has to read with a patient tentativeness and an awareness of the intentional, multivalent quality of the language.”16

Section three, Psalm 43:1-5, moves from soliloquy to dialogue. The section is again closed out by nefesh thinking. Peter Craigie remarks that in this third section, Psalm 43:1-5, “the internal dialogue of lament is turned into an external dialogue with God.” The more self-conscious “I say to God, my rock,” of Psalm 42:9 is the earnest direct appeal of 43:1, “Vindicate me, O God, and defend my cause.” Up till now, the seeker has been largely communing introspectively with her own soul. The section begins with an abrupt plea to God set against a typical psalmic protest against the ravages of deceitful and unjust enemies.

In Craig Broyles’ interpretation, “the range of expression found in the Psalter is determined by this polarity of praise and protest” and we meet it in full force here.17 The agitated opening yields to the calm declarative statement, “For you are the God in whom I take refuge.” This comes almost like a calm after storm. The calm doesn’t last long, however. The interrogating mode flashes forth in “Why have you cast me off?” followed by the rapidly repeating second stanza, “Why must I walk about mournfully because of the oppression of the enemy?” There is much emotional and textual twisting and winding and backwards and forwards motion going on here and the syntax seems designed to replicate the seeker’s own wrestlings with God. It is an important moment in the song. The synthetic parallelism employed in following “why cast me off” with “walking about mournfully” is a standard Hebrew tactic to get attention and to emphasize the point, the way we might use exclamation points or underlining.

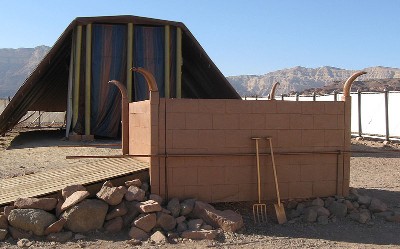

Stylized view of God’s altar: here is what the Psalmist prized above all else.

Stylized view of God’s altar: here is what the Psalmist prized above all else.Many Moods

Then comes a passionate and, for many, delightful interlude. The writer takes flight on gossamer wings of hope in the rhapsodic-like request in verses 3-4, inlaid, jewel-like, between verses 1-2 and 5. It goes: “O send out your light and your truth; let them lead me; let them bring me to your holy hill and to your dwelling. Then I will go to the altar of God, to God my exceeding joy; and I will praise you with the harp.” The vocative mood has the power to lift us higher and the poet undergirds it with powerful imperatives – “Let then lead me, let them guide me.”

What does it mean for God to send out his light and truth? Light dispels darkness. The references to the tabernacle and festivals in the previous psalm and the finely alliterative “holy hill” in 43:3 most likely encouraged the poet to think of the lampstands that burnt steadfastly in the tabernacle. They were symbols of God’s enduring presence; a recollection made all the more poignant now because the seeker is cut off from these very symbols (Exodus 37:17-24).

What would it mean, however, for God to send out his truth? This word truth is transliterated ‘emet and is tied to the shoresh from which we get the Hebrew word “Amen.” Emet here is translated “firmness, faithfulness, truth.” The broader term conjures up notions of God’s reliability and sureness, as in Genesis 24:48 where Abraham’s servant thanks God for leading him in “a sure way.” The term is also associated with stability or security, as in Isaiah 39:8 where Hezekiah says “there will be peace and security in my days.” Emet is also an attribute of God in Psalm 71:22, “I will also praise you with the harp for your faithfulness, O my God.” In Psalm 40:11 emet is linked as well to God’s steadfast love, “Let your steadfast love and your faithfulness keep me safe forever.” Kraus catches the mood perfectly: “God himself must intervene, and by means of his emissaries (‘light’ and ‘faithfulness’) bridge a dark chasm.”18

The ardent outburst of hopeful praise and promises to pray at God’s altar after deliverance are checkmated again by the reappearance of the rhetorical question and answer format, “Why cast down?” in 43:5 which ends the lament. The call to praise is set as a hope; the verb “cast down” seems more compelling. Cast down is from the verb shachach, meaning, to bow, to be bowed down. The root shoresh has the meaning of being prostrated, humbled by experience. Isaiah 2:11 says (in the Qal, here) “the haughty eyes of people shall be brought low, and the pride of everyone shall be exalted,” referring to God’s leveling wrath. It can refer to city walls laid low and is related to Proverbs 12:25, ‘Anxiety weighs down the human heart.” The depths are clearly being reached in this Psalm but there is still encouragement given to seek God…even in the depths.

A Realistic Spiritual Quest

In summary, Psalm 42/43 is part of what Craig C. Broyles calls a “lament of God’s disfavor.” There is little direct praise of God involved in Psalm 42/43. There is a promise to praise God once the complaint of separation from God is eased.19 In Broyles’ analysis, as noted above, both praise and protest were considered integral for Israel’s praying community and it is protest that clearly dominates here. So, what is this psalm saying about God? Here is a key question for an age sometimes confused in its commendable quest for a deeper spiritual life. This paper, written from an evangelical Christian perspective, raises some of the issues involved in a believer’s wrestling with the absence of God. This is indeed a challenging subject but one that can add levels of depth and meaning for an often-overlooked aspect of contemporary spirituality.

Psalm 42/43 with its fierce honesty and tendency towards complaint is a wake-up call for those who think that spirituality means only the ever-upward ascent to God or the coddling and cosseting of one’s own private, devotional fantasies. In an age where commerce has even invaded the most sacred precincts of the religious quest, it might be hard to sell tickets to an event where the exploration of God’s absence is discussed. Psalm 42/43 thus checks our spiritual complacency, our tendency to reduce God to our level. It reminds us of what the great saints and mystics have documented, that being in communion with God or however we define the Higher Power can lead to moments of “disquietness,” what have been called dry periods or dark nights of the soul.

Being mindful of this reality can steady seekers in their often-impatient walk with God. John Goldingay says it well: “Although Christ has come, we experience times when God seems absent, forgetful, abandoning, dead… At such times we may pour out our despair to God…and to plead with God for a new experience of Christ coming to fetch us and to lead us home to God’s own presence.”20 It is noteworthy that the pronoun phrases “my God,” “my rock,” “my help,” “the God in whom I take refuge” in Psalms 42/43 evidence the closest possible connection between the seeker and God even if expressed sometime in the negative mode. It is reminiscent of the emotional point made in Psalm 22:1 where the cry of despair is still couched in personal, possessive terms: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Another important reflection is that the psalmist is praying against the backdrop of a very real tradition of Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained, at least typologically. If the east door of the tabernacle as the place where Israel was to meet God was a pointer back to the east gate of Eden barred to Adam and Eve, then the tradition of striving for a happy return is an old one indeed. The cataracts and waterspouts are to be expected along the way, as with John Bunyan’s pilgrim, but they can be brooked and forded just as the Red Sea barrier was effectively breached by God’s mighty power. If the Lord was not on his side, another psalmist wrote, the waters would have prevailed. This is why the closing note in psalm 42/43 is defiantly hopeful: “For I shall again praise him, my help and my God.” The solitary adverb” again” hits with real force as it is placed before “praise” and for very good reason – the optimism may be muted and cautious but it is there.

Also relevant to this discussion is this fact: we live in a time when the institutional church seems in a bad way. “Move over pastor, move in Holy Spirit” was the recent bold title of one seminar on the evangelical speaker circuit. How I Survived the Church and They Like Jesus but not the Church are other signposts from the world of religious publishing. Other sidelong jabs at the organized church are not as tactful. Set against this is the repeated claim in Psalm 42/43 the seeker wants desperately to go to church to express his praise to God. It shocked government officials during the COVID-19 pandemic that some North American Christians across a wide spectrum made such a to-do about being able to attend public services. The poet of Psalm 42/43 craves to return to the altar of God; that is where he will best sing his praises (43:3). That is where he will find rest. This attitude surcharges the poems, holds them together in a dynamic embrace drawing strength from the sober New Testament charge in Hebrews 10:25 that proclaims “Let us not give up the habit of meeting together…but let us encourage one another – and all the more as you see the Day approaching.” Both authors – the Psalmist and the Apostle – knew that spirituality thrives best in communion with others.

This attitude surcharges Psalm 43. It acts as a corrective to the commercialized spirituality and sometimes shallow mysticism extant today. Barbara Green summarizes the case very well:

If Scripture is to continue to be revelatory in our lives, as it is meant to be…we need to allow it some room to maneuver. Being the densely patterned and brilliantly told narrative of the many dealings of God with other human beings and them with God, it will offer many surprises. Its metaphors have the capacity to sidle up to us with apparent innocence because they interest us but do no immediately threaten us. They blindside us, suddenly disclosing to us something we might have screened out had we seen it coming…They offer us self-knowledge in good company, both with other fallible human beings and a compassionate God. Partly a matter for our mind and reason to puzzle out, they also can cut through to our hearts and so change our wills and habits, perhaps not in one huge shift but in many installments and treatments.21

“Self-knowledge in good company.” There is a missing dimension in today’s spiritual seeking. Its antidote may be found in a deeper acquaintance with Psalms 42 and 43.

Endnotes

1 Richard J. Foster, Celebration of Discipline: The Path to Spiritual Growth (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1988), page 109; Kenneth J. Collins, “What is Spirituality? Historical and Methodological Consideration,” Wesleyan Theological Journal, Number 31 (1996) 87.

2 Sandra M. Schneiders, “Theology and Spirituality: Strangers, Rivals, or Partners?” quoted in Kenneth J. Collins, “What is Spirituality?” Wesleyan Theological Journal, Number 31 (1996) 89.

3 Eugene Peterson, Subversive Spirituality (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), pages 32-42.

4 John Calvin, “Commentary on the Book of Psalms,” quoted by Willem A. VanGemeren, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Volume 5 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing, 1991), page 6.

5 Barbara Green, Like A Tree Planted: An Exploration of Psalms and Parables Through Metaphor (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1994), page 11.

6 Philip Keller, A Shepherd Looks at Psalm 23 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1970), page 60.

7 Peter Craigie, Psalm 1-50: Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 19 (Waco: Word Books, 1983), page 325; Willem A. VanGemeren, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Volume 5, page 330; Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalms 1-59: A Commentary (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1988), page 438. Kraus cites Gunkel and Begrich in support.

8 Peter Craigie, Psalms 1-150 (Waco: Word Books, 1983), page 325.

9 Bernhard Anderson, Out of the Depths: The Psalms Speak for Us Today (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983), page 83.

10 James Luther Mays, Psalms (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1994), page 173.

11 Quoted in Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalms 1-59, page 441.

12 Hans Walter Wolff, Anthropology of the Old Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress press, 1974), pages 24-25.

13 John Goldingay, Songs from a Strange Land: Psalms 42-51 (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1978), page 43.

14 Mitchell Dahood, The Anchor Bible: Psalms (1) 1-50 (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1966), page 258.

15 Marvin R. Wilson, Our Father Abraham: Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989), pages 150-153.

16 James Luther Mays, Psalms, page 6.

17 Craig C. Broyles, The Conflict of Faith and Experience in the Psalms: A Form-Critical and Theological Study (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1989), page 52.

18 Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalms 1-59, page 442.

19 Craig Broyles, The Conflict of Faith and Experience in the Psalms (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1989), page 61.

20 John Goldingay, Songs from a Strange Land (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1978), page 47.

21 Barbara Green, Like A Tree Planted (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1994), pages 19-20.