Prophet Complained to God…and Lived to Tell the Story

By Neil Earle

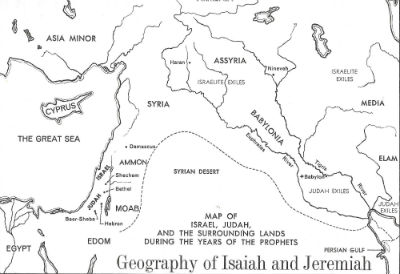

Part of Jeremiah’s “burden” with Yahweh is his intense sense of ambiguity about the prophetic calling.

Part of Jeremiah’s “burden” with Yahweh is his intense sense of ambiguity about the prophetic calling.Jewish sage Abraham Heschel described Israel’s prophets as some of the most disturbing people who have ever lived. Their sense of being overwhelmed before a mysterious God, of human inadequacy against an angry religious-political establishment and a resulting feeling of abandonment, of many “dark nights of the Soul” – all of this spills out in the provocative words of Jeremiah 20:7-13. In an era when half of America’s pastors have thought seriously of abandoning their profession,1 Jeremiah’s complaint in 20:7-13 may repay close study.

Jeremiah lived when the nation of Judah had been guilty of such gross sins as infanticide (2 Kings 23:21) not long before. God’s wrath was ready to fall and the young Jeremiah was his lonely messenger of warning. Monarchy, temple and priesthood were corrupt but held absolute power. Jeremiah felt like quitting more than once and let his feelings pour out in fervent complaint to God. But he always held fast in the end and left us a brilliant report of his experiences that can inspire us today in our own walks with God.

True Confessions

Jeremiah 20:7-13 is part of a famous subsection within Jeremiah 11-20, variously called the “Confessions,” “Complaints,” “Petitions” of Jeremiah. Jeremiah 11:18-23; 12:1-6; 15:10-12; 17:14-18; 18-23; 20:7-13; 14-18 includes laments, monologues, dialogues and disputes with adversaries and with the Lord. They provide “a remarkable picture of the personality of Jeremiah and reveal something of the inner struggles of the prophet.”2

Part of Jeremiah’s “burden” with Yahweh, which finds full expression in Jeremiah 20:7-10, is his intense sense of ambiguity about the prophetic calling. He was called to the office at a very young age (1:6). Something bad – really bad – is about to happen to a sinning heedless nation. God will uproot his chosen people from Judah – lock, stock, and barrel – and not even intercessory prayer is going to stop that determination (Jeremiah 7:14; 11:14; 14:11). Their sins under King Manasseh (c. 687-642 B.C.) – including child sacrifice – have offended so badly that not even King Josiah’s reforms (640-609 B.C.) had changed the nation’s trajectory. Yet they still thought of themselves as “God’s favorite people” (Jeremiah 18:18). Jeremiah will conduct a contentious last warning ministry while caught between Jerusalem’s apathy and overconfidence and the divine intent.

God the Deceiver?

Commentators appreciate Jeremiah’s literary skills and wordplay. Take the use of the verb patah (to be gullible), mentioned twice in Jeremiah 10:7 and again in verse 10. “Patah” has rich shades of meaning. The New International Version (NIV) follows the traditional rendering of patah as “deceived” – “You have deceived me, O Lord, and I was deceived.” The Tanak, the Jewish Publication Society version, and the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) both use the word “enticed.” The wording goes: “You enticed me O Lord and I was enticed. You overpowered me and you prevailed (Tanak)” and “O Lord, you have enticed me, and I was enticed; you have prevailed” (NRSV).

The New King James Version (NAV), however, gives a more “psychological” undertone – “O Lord you induced me and I was persuaded, you were stronger than I and have prevailed.” Christians can relate to this. Christian calling can look very appealing when one first sets out to answer it in the bloom of youth. Yet time can erode any commitment. Jeremiah 20:7 evokes a familiar sense of wear and tear.

Jeremiah had big shoes to fill – the saintly Samuel, rugged Elijah and Elisha, multi-talented Isaiah, eloquent Micah, and fervent Hosea. Who wouldn’t feel inadequate standing in such an honorable tradition?

Patah unlocks Jeremiah’s emotional state. The word pictures associated with it are very unflattering, especially when directed towards Yahweh! Emotionally they convey associations of reacting to a hyped-up used car salesman (“You have enticed me”) or the aversion felt towards deadly conspirators. The term appears in that strange passage 1 Kings 22:20-22. The context is Yahweh’s impatience with King Ahab. Yahweh wants Ahab to die in battle, a purpose to be effected by Ahab’s setting out to battle thinking God is on his side.

“The Lord asked, ‘Who will entice Ahab so that he will march and fall at Ramoth-Gilead…[A] certain spirit came forward and stood before the Lord and said, ‘I will entice him.’ ‘How?’ the Lord asked him. And he replied, ‘I will go out and be a lying spirit in the mouth of his prophets.’ Then he said, ‘You will entice and you will prevail.’ So the Lord has put a lying spirit in the mouth of all these prophets of yours; for the Lord has decreed disaster upon you’” (Tanak).

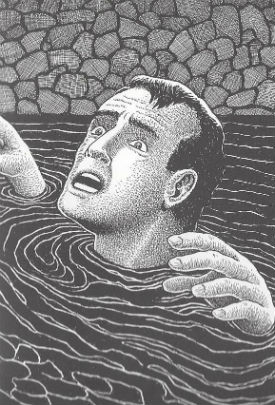

Jeremiah almost died in miry prison.

Jeremiah almost died in miry prison.“I Can’t Do This!”

Jeremiah’s image of Yahweh as a divine Trickster evidences his mental convulsion. The noun peti derived from patah “characterizes a type of person who is youthful, imprudent, and hasty, therefore gullible and foolish, but also in need of instruction.”3 This fits the narrative context of Jeremiah. In Jeremiah 1:6 the prophet replied to his inaugural vision, “Ah, Lord God! I don’t know how to speak, For I am still a boy.” This protest met Yahweh’s comeback: “Do not say, ‘I am still a boy,’ but go wherever I send you and speak whatever I command you. Have no fear of them, for I am with you to deliver you, declares the Lord” (Jeremiah 1:7-8).

Yet Jeremiah later protests: “You have gulled me, O Lord and I was gullible!” Jeremiah 20:7 is clearer, “I have been a laughingstock all day long, everyone mocks me (NRSV).” This rendering of “laughingstock” introduces another word with sober allusions – it derives from lishoq and is repeated twice in Job 4:4. The tie-in with Job—the Paragon of Depression – underscores the desperation of Jeremiah’s attitude in this complaint.

Jeremiah 20:8 fills out the reason for the “laughingstock” charge. “For whenever I speak, I must cry out, I must shout, ‘Violence and destruction!’ For the word of the Lord has become for me a reproach and derision all day long.” No wonder he is depressed – he is seen by his neighbors as the “bad news bearer,” “the man with the sandwich board,” we would say today.

“The Horror! The Horror!”

There are reasons for Jeremiah’s feelings of discomfort. The phrase “violence and destruction” (hamaswasod) is revealing. Hamas here and in Jeremiah 6:7 is the characteristic Hebrew word for “violence, wrong.” It attacks the “rude wickedness of men, their noisy wild ruthlessness.” Hamas appears ominously in Genesis 6:11 (NIV) – “Now the earth was corrupt in God’s sight and the earth was full of violence (hamas).” Hamas lives on today as the Arabic term for terrorist groups in the Middle East. This is what Jeremiah had to threaten his people with! No wonder he is unpopular. Worse! A laughingstock (lishoq), for God was patient and while he waited for repentance Jeremiah looked like an imposter.

What aggravated all this was God’s use of other more ruthless nations to punish his people (Jeremiah 21). His calling to sound a last-ditch warning effort to Jerusalem to turn to God or Babylon would sack the city earned him the title of traitor. When the Babylonians repulsed the Egyptians at the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC Jeremiah’s sense of impending doom for his city and people launched his powerful Temple Sermon (Jeremiah 36).4 It no doubt also inspired his warning about 70 years of captivity in which he mentioned he had been preaching this warning for 23 years (Jeremiah 25:1-3).

Around 603 B.C. the obstinate Jewish King Jehoiakim had been forced to pledge allegiance to Babylon but later rebelled, against Jeremiah’s advice (Jeremiah 26)!5 Judah’s time was running out but its leaders had a false confidence based on Yahweh’s deliverance from the Assyrians some one hundred years before – indeed this false feeling of security is one of the major themes of Jeremiah’s prophecies.6 The official, sanctioned prophets were preaching a popular “God’s in his temple/All well with the world/Babylon will leave us alone” message.

The acme of this hostility is seen in the priest Pashhur’s putting Jeremiah in the stocks, an event which immediately precedes our passage (Jeremiah 20:1-6). Later he is sent into a deep miry pit up to his neck. Prophets are rarely popular. Given Jeremiah’s mention of “my persecutors” in Jeremiah 20:11, this major Complaint we are analyzing could be placed anywhere around the time 598 B.C. when Babylon marched west again and Jehoiakim was killed (“terror on every side!” – Jeremiah 20:11) to 597 B.C when Jehoiachin, his son, was carried off to Babylon. Or perhaps it occurred as late as 594-593 B.C. when Jeremiah had to withstand the overweening optimism of the false prophet Hananniah. Hannaniah preached that not only would the Temple furnishings be restored from Babylon but that Jehoiachin would return (Jeremiah 28:1-4).7

Not so, said Jeremiah.

INFANTICIDE: Cistern with child's bones from 600s BCE.

INFANTICIDE: Cistern with child's bones from 600s BCE.“God-Troubled Man”

Judah’s fatal hardheadedness helps explain Jeremiah’s frustration with the people, as well as with God. He is a laughingstock, yes, but he is also a “God-troubled man.” And yet…and yet, in his heart of hearts his frustration conceals great love. In the depths of his despairing Complaint, there flashes forth a divine fire all the prophets had. Verse 9 states: “I thought, ‘I will not mention Him, no more will I speak in His name’ – But [His word] was like a raging fire in my heart, shut up in my bones; I could not hold it in, I was helpless.” This is a turning point – an emotional center of the book. It reveals sterling dedication to God and his calling that would come to the fore after Complaint. For a harassed prophet out of sorts with everyone around him a sense of strong calling is a powerful tonic!

Jeremiah eloquently compares God’s word to fire. The active participial actually means “flaming fire” (k ‘es bo’eret) and recalls potent well-known references across Israel’s history. It is especially linked with Yahweh’s manifestations of omnipotent power seen in such passages as Exodus 24:17, Deuteronomy 4:24 and 9:3, and Isaiah 33:14. For Jeremiah, the fire of persecution without is matched by the fire of divine conviction within! His despair battles his sense of divine calling and the prophet is caught in the pincers of great emotional stress – “I could not hold it in.” The Word Biblical Commentary notes the prophet’s exhaustion from trying to hold back the word of God. Yet the calling wins out!

When hard-pressed he becomes more eloquent than ever. Colorful word pictures cascade forth from an obviously talented preacher. To the fake priest Pashhur in 20:3-4 he charges: “The Lord’s name for you is not Pashhur (“son of the god Horus”), but Magor-Missabib (‘Terror on every side’).” Jeremiah decrees: “I will make you a terror to yourself. “ In Jeremiah 20:10 the prophet himself is tagged with the same nickname. “Here comes old Magor-Missabib,” his enemies might have said. In English the poetic effect of Magor-Missabib is that of a clever resemblance of sound between syllables that make a memorable put-down, not unlike “helter skelter” or “mumbo-jumbo.”

Puns and poetry express grim debates between true and false prophets. The reappearance of patah in verse 10 may be a rhetorical retort to his critics: “Yahweh can trick me but you will not,” seems to be Jeremiah’s defiant response. This emotional somersault sets up the abrupt turnabout in Jeremiah 20:11, a sense of defiance kicked off with the assuring faith remark, “the Lord is with me.” For a true servant of God, energy flows from pondering the power of the Almighty God they served. Something has changed in the prophet’s outlook:

[This] marks the rhetorical center of the unit and also the transition. From lament and complaint the confession shifts to the strongest words of trust and confidence. Despite the fact that Yahweh has overcome him, and that enemies tried to do the same, Jeremiah has assurance that they will fail. Furthermore, he also has the assurance that Yahweh is not his enemy.8

All’s Well that Ends Well!

The sense of relief surfaces in the exciting word picture that follows. Jeremiah 10:11 describes Yahweh as a gibbor ‘aris, a reference to the gibborim, the elite fighters, the flower of Israel’s army. “Special Forces” we would call them today. Indeed the last two verses are a festival of powerful language. Isaiah, for example, had associated el-gibbor with the coming Messiah and the tradition dates back to at least the Song of the Sea in Exodus and the Psalmic recitation praising “Yahweh, strong and mighty, Yahweh, mighty in battle” (Psalm 24:8).9

This Mighty Warrior is, in verse 12a, the Lord of Hosts, a typical Jeremiah term for the Almighty. This all-conquering, all-knowing God also “sees into kidneys and heart” where the kidneys, kelayot, is the Hebraic way of connoting the psychological life while the heart, leb, is the seat of the will. “For to you I have committed my cause,” adds Jeremiah in verse 12b. As Thompson notes, here is legal language. Those who sought to collect evidence against on him (verse 10) will find Yahweh is his defendant.

Now there is nothing left to do but to exult in a typical Hebrew effusion: “Sing to Yahweh, give praise to Yahweh,” was a standard way of ending even a morbid opening with God (20:13). Thus self-confessed “poor man” of Psalm 40:17, 69:29, 70:5 (AV) models the humble and grateful Prophet caught up in the divine assurance of victory. Yahweh is ever the Defender of the poor and Jesus himself promised the kingdom to the poor in spirit.

Textually and emotionally there is a vast distance between a feeling of being “gulled” by Yahweh – where Jeremiah began – to the exultant cry at the end. Jeremiah was living in a time when God was doing something new – something unprecedented and horrific, the uprooting of an entire people for gross sins. But out of it will come a renewed, purged, transformed people committed to a New Covenant of the heart (Jeremiah 31:21). Jeremiah’s Confessions are a lasting linguistic treasure from these transitional times.

Like a blinded but determined boxer thrashing and lashing out wildly sometimes, he is nevertheless determined to stay in the ring. God’s words were like a fire inside and he could not turn away. All who share a divine calling can be encouraged by this legacy. Jeremiah’s emotions often failed him but his faith never did!

We can take heart from this. God’s calling leads us into some narrow straits but God strengthens us in our weakness. Jeremiah’s life experiences and precious words handed down in such minute detail declare that this is true. Thanks be to God!

1. Rujon W. Morrison, “The Pastor’s Struggle with Self-Esteem,” Christian Counseling Today (2001 Volume 9, Number 1, pages 50-51. (This was originally a class paper for Fuller Seminary.)

2. J.A. Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980), page 88.

3. Ernst Jenni and Claus Westermann, Theological Lexicon of the Old Testament: Volume 2 (Peabody, Mass., Hendrickson, 1997), page 1038.

4. J.A. Thompson,

5. William LaSor, David Hubbard and Frederick Bush, Old Testament Survey: The Message, Form and Background of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), page 218.

6. Thomas W. Overholt, The Threat of Falsehood: A Study in the Theology of the Book of Jeremiah (Naperville: Alec R. Allenson Inc, 1970), page 3. “The presence of the temple in their midst seems to have symbolized for them a guaranteed national security.”

7. William L. Holladay, Jeremiah 1: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Jeremiah (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986), page 551.

8. Craigie, Kelley and Drinkard, Jeremiah 1-25, page 274.

9. G.J. Botterweck and H. Ringgren (eds.) Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, pages 1505-05.