Handling Difficult People: Faith-Based Solutions

By Neil Earle

John D. Rockefeller put a very high premium on the ability to work with people.

John D. Rockefeller put a very high premium on the ability to work with people.Will Rogers, the great cowboy philosopher, was reputed to have said, “I knew someone who said, ‘I never met a man I didn’t like.’ Well, he never met some of the people I knew.’”

Most of the conflicts people experience in the Western world, especially, is the day-in day-out drip/drop/drip of dealing with problems at work or on the job or at home with the gas and electrical bills. What John D. Rockefeller said more than 100 years ago rings true: “The ability to work with people is as purchasable a commodity as coffee or sugar, but I’ll pay more for it than any other ability under the sun.” This matches the former steel company exec who said that “a railway is 99% people and 1% iron.”

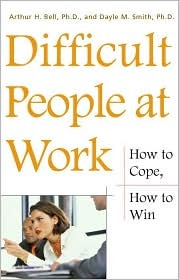

In their helpful little book, Difficult People at Work: How to Cope, How to Win, authors Arthur H. Bell and Dayle M. Smith report that many companies typically invest 90% of a new employee’s first year salary in hiring and training. They know that 85% of work/productive problems involve a bad “fit” on the job or the torpedoing of office morale or the congregation through personality conflicts. This sets everyone back.

In other words, it pays to know how to handle difficult people.

“Should Rambo Rule?”

The former Chrysler executive Lee Iacocca had to face his own anger: “I was full of anger, and I had a simple choice: I could turn that anger against myself with disastrous results or take some of that energy and try to do something productive.”The Biblical writer James cautions: “My dear brothers, take note of this: Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry, for man’s anger does not bring about the righteous life that God desires” (James 1:19-20).

Lee Iacocca learned to channel his anger.

Lee Iacocca learned to channel his anger.As Bell and Smith correctly observe: “Physically and emotionally, mangers break down when day in day out, they attempt to manage by means of blood pressure and Maalox. Today’s outburst has to be repeated, with even more intensity, tomorrow, and employees come to expect an ‘encore’ to the boss’s fits of rage. The boss finds himself or herself always having to up the ante on anger. What used to take only a harsh glance now requires a ten-minute tantrum” (page 41).

The penalties of the Rambo approach to leadership are often dire:

1. Good employees often quit.

2. Good ideas are never heard.

3. The angry manager suffers corporate isolation.

4. The manager reveals his own lack of immaturity and lack of “smarts” to the higher ups – the S.O.Ps are “getting to him.”

5. As Lee Iacocca knew, the physical and emotional problems are also heavy. Far better to engage Difficult People with a thoughtful strategy as this article covers.

“The Dirty Dozen”

Bell and Smith identify the “Dirty Dozen,” the twelve unfortunate personality types they describe as S.O.Ps – “Sources of Pain” for the people who must work with them or around them. They are the primary sources of company frustration, anger and dissatisfaction. Here they are:

The Backstabber

The Liar

The Blamer

The Short Fuse

The “Yes, but”

The Busybody

The Politician

The Silent Martyr

The Bitter Recluse

The “Voice in the Wilderness”

The “One True Friend”

The Board of “Star Chamber”

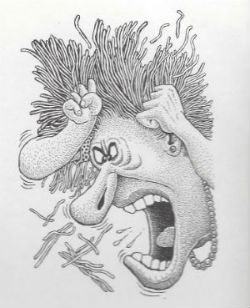

Beware the Short Fuse! Basil Wolverton artwork

Beware the Short Fuse! Basil Wolverton artworkSome of these troublesome folks are quite familiar. The Busybody and the Politician, for example, are almost omnipresent in all firms…and churches! Ask any pastor. Others embody traits that are hard to summarize, such as the “Star Chamber,” named after a 1500’s English high court which terrorized the realm. Today these are the people who “form a secretive clique that criticizes more than it contributes” (page 79), a judgmental “silent minority” who think alike and can be real bottlenecks to smooth functioning.

Bell and Smith advise on the tactic of trying to smoke them out in regular worker involvement or staff planning meetings. In focus groups or smaller task forces the super-critics can be separated from and isolated from their cliques. In this more manageable setting the manager or team leader can force them (diplomatically, of course) to come up with hard objections rather than personal trivia or chronic foot-dragging.

This will “call their bluff” but in a discreet, professional environment. As the authors say, even some on the Star Chamber will feel encouraged when they sense that that they do have positive contributions to make. The key is to help them learn to feel more part of a bigger team that is accomplishing constructive, worthy goals.

“Creative Listening”

This one-two punch of “identify problem/find solutions” is what makes “Difficult People” such a helpful and practical read.

Understanding people and why they do what they do is a vital key to success, said J.C. Penney.

Understanding people and why they do what they do is a vital key to success, said J.C. Penney.A real strength of this book is the third chapter on Anger, titled “Active Listening.” This is not often stressed in “how to” books on dealing with difficult people. In other words, the leader or pastor’s own attitude is often not addressed. Anger is the most common reaction to the stresses other people bring to bear on bosses and it is never the best reaction. Here is where Bell and Smith intersect with a Biblically-based approach to getting along. The Scriptures that deal with anger are many and broad. They include:

- “Hatred stirs up dissension, but love covers over all wrongs” (Proverbs 10:12). Good managers/pastors know how to successfully interact.

- “Reckless words pierce like a sword, but the tongue of the wise brings healing” (Proverbs 12:18). Remember, sometimes people criticize because they know a lot about a subject and think a valuable issue is at stake. Don’t always assume the worst.

- “Every prudent man acts out of knowledge, but a fool exposes his folly” (Proverbs 13:16). “Knowledge” or “know-how” is vital. Bell and Smith fail to mention that managers often forget to outline visible goals and measurable performance standards to their subordinates. That is a recipe for creating tension.

- “A patient man has great understanding, but a quick-tempered man displays folly” (Proverb 14:29). J.C. Penney said: “An understanding of people and why they do what they do is one of the most vital attributes to executive success.” Good managers ask: Why is the Exploder (for example) the way he is? How can I help him?

“A gentle answer turns away wrath, but harsh words stir up anger” (Proverbs 15:1). Don’t forget “It takes two to tangle.” The ability to wisely handle criticism is a vital prerequisite for any leader. The Voice in the Wilderness, for example, can easily turns into the “whistleblower” on problems real or imagined because her memos and suggestions are never even read let alone answered. “Oh, it’s her again.”

The wise strategy is to thank the person for their communications and make sure they know to whom they are going. Outline to the Voice who is the best person in the company to send them. Alert top mangers to the fact that these memos will be coming and suggest how to adjust. One military contractor turned this potential lemon into lemonade by making sure the Voice was included in company social life. He then created a “Pulse Award” for people who kept a finger on the factory floor as a whole.

A helpful book full of practical advice on dealing with personality conflicts.

A helpful book full of practical advice on dealing with personality conflicts.Effective Tactics

The Backstabber can never be rewarded, says Bell and Smith, and it often takes some concentrated attention to smoke them out. Schedule brown-bag lunches with your team, try to build team spirit, they advise. Check out derogatory information circulating quickly and privately. Outline the ideal corporate culture to the person once you have correctly identified them. Positively hold out the proverbial right hand of fellowship so that they are given a chance to prove they still want to be part of the team, maybe a career advance (“We’re looking for people who show awareness.”) If they have to be dismissed at least the office staff will know that the boss took the time to try and make things work. Jesus’ top apostle is proverbial for deserting his Leader but we all know what happened – mercy worked.

The “Yes, better” can be handled by having her write out her objections in a carefully crafted memo or e-mail. As Bell and Smith note: “The act of writing requires that half-baked thoughts be filled out into sentences and then structured into a cogent argument with evidence and recommendations” (page 57). In the process, the Objector often sees through his own flaws in logic. This self-correcting method can avoid costly confrontations. Short Fuses and Blamers can often be outflanked at public meetings by the manager asking, “Does anybody else feel that way?” If you have a smoothly functioning team, others will come to your aid and the point will be noted by even the Silent Martyr (“I’m the only one who cares around here”) and the Bitter Recluse (“Keep away, you’re all getting in my way”). Above all, regular displays of genuine concern and appreciation – good feedback for good service – in an often cold, clinical office pod can work wonders.

Attitude, Attitude

“Attitude means mental posture relative to the other individual,” writes Robert Morton. “Technique without attitude won’t work. Why? Because spiritual principles are at work when we deal with other people” (A Basic Course in Human Relations, page 98).

Simply learning a crafty “bag of tricks” won’t work. People can usually spot when they’re being manipulated. Managers beware: Employees can detect the difference between genuine concern for them, the firm or the congregation and corporate “phony baloney.” The greatest key to human relations, to the wise handling of people, was given 2000 years ago: “In everything, do to others what you would have them do to you” (Matthew 7:12). Bob Morton advises, “In any dispute, think: ‘How would I like to be handled.’”

Bell and Smith’s helpful little book reaffirms that life principles and work principles are often one and the same. Almost every human endeavor intersects sooner or later with solid Biblical principles. Such themes as active listening, reducing anger, thinking of what is best for even the difficult problem people and genuinely wanting to help people become more productive will never fail. Review these principles often. You’ll always be glad you did.