History Shows: Never Give Up On Hope

By Neil Earle

In this crazy seemingly out-of-control world it is sometimes helpful to take a long look back. Yesterday I was scanning my mammoth Timetables of History given to me by friends in the 1980s to see what the world was going though in 1921.

First off, Hitler’s recently formed storm troopers were already terrorizing political opponents in the cities of Germany, still in shock from World War One. An Allied Reparations Commission of French and British fixed German “war liability” at $32,000,000 and gave Hitler a great bone of contention to chew on.

In music both Caruso and Irving Berlin were holding forth and the BBC was founded. Albert Einstein would win the Nobel Prize for Physics, a personality who would loom larger later in the century, while George Bernard Shaw was dissecting British society in the theaters of London.

One hopeful sign was a massive Disarmament Conference in Washington that brought Japan, the British Empire and the Americans together to end an arms race at sea and – surprisingly – it worked!

“The War That Killed God”

Clearly the hangover from the unprecedented holocaust known as WW1 was still be-devilling 1921. “The events of 1914-1918 changed everything,” writes Harvard historian Niall Ferguson. Some called it “the war that killed God,” at least among Europe’s impoverished populations still not recovered from burying the dead.

Our current preoccupation with Iraq and Iran traces most notably to those nations carved from the corpse of the old Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of 1914-1918. In short, “Disillusion” was American historian’s Barbara Tuchman’s one-word summary of the period in her 1962 prize-winning The Guns of August.

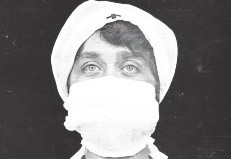

Pandemic! Philadelphia nurse from 1918-1919.

Pandemic! Philadelphia nurse from 1918-1919.One of the enduring lessons of 1914 was that the Great Powers must not be drawn into complicated third-party conflict, a lesson Adolph Hitler violated in 1939 and for which we all paid the price. Still, we do learn. For 72 years since Hitler our Great Power faceoffs have been scary enough, but limited. An element of rationality has prevailed which WW1 helped instill. The slaughters on the Western Front stagger us even now. The French army lost 50,000 men to gain 500 yards of territory in Champagne. A million Frenchmen and Germans eventually died in the struggle over the frontier fort at Verdun. These losses shook France to her foundations. In some ways she never has recovered.

Wars have consequences, no doubt.

“A Lost Generation”

The death of millions of men in what seemed a lost cause helped create a lost generation. Out of the chaos of war came the socialist super-state, the Soviet Union or Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which seemed to many at the time a hopeful alternative to Western-style capitalism. Many were still recovering from the influenza epidemic in 1918-1919 which killed 55 million around the world and about 550,000 in the United States – terrible for a population of 105 million.

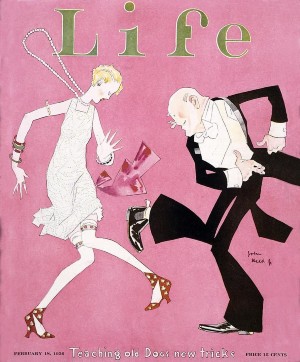

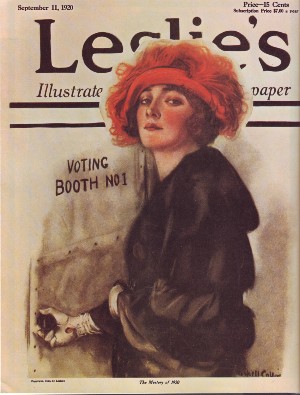

A hard new cynicism gripped many people, later evoked in “A Farewell to Arms” by Ernest Hemingway who was warming up to become a best-selling author. The war saw a noticeable backlash against conventional morality and mores. The new, disturbing ideas of Sigmund Freud now seemed superior to the sermons being preached on Sunday. The National Institute for Industrial Psychology was founded in London in 1921. Albert Einstein’s thoughts on “relativity” began to enter the vocabulary as an excuse for “anything goes,” soon the title of a Cole Porter song. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” (the character was a war veteran) would capture the spirit of the 1920s: “Forget Europe, let’s have another drink.” A leveling trend was in vogue, moving millions away from trust in authority. The Premier of Japan and the leader of Portugal were murdered. Women and labor unions made some important gains. The ladies had won the vote the year before after serving heroically on the home front and the defense plants. This would eventually prove one of the biggest changes of all.

THE GAME CHANGER – With the automobile, life in America would never be the same.

THE GAME CHANGER – With the automobile, life in America would never be the same.“On the Other Hand…”

The world before 1914-1918 had seemed so secure, so stable. “God’s in his heaven/All’s right with the world” a Victorian poet had sung. This partly explains the later tendency to write off WW1 as a totally unredeemed failure, especially the peace treaties at Versailles that ended the war. Much abuse has centered on those striped pants diplomats. Barbara Tuchman and another lady historian, Margaret MacMillan, are more careful. Some atrocities were over-reported while civilized norms had still held fast overall in spite of the horrors of trench warfare. German and British troops did mingle in No-Man’s-Land that first Christmas of the war and Germany had surrendered on honorable terms advocated by American President Woodrow Wilson.

Wilson’s urgent diplomacy probably shortened the war from being an even more pointless fight to the finish. MacMillan argues in Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World that the efforts of those sincerely committed to a just peace with Germany at the Versailles Conference in 1919 were “not completely wasted.”

In the end Germany was not dismembered as some wanted. The American delegation to Paris helped see to that.

“A New Spirit”

Peace conferences often have fatal blind spots but MacMillan argues for a new spirit abroad after 1919. Somehow nations and national groupings and their leaders knew things had changed. Leaders were going to be held more accountable to their people. In 1921 a sense of a basic moral order operating even among nations lingered from the long peace of 1815-1914.

The Geneva Conventions and the League of Nations builders were busy in 1921. They did articulate standards that could be subverted for a while but never completely overthrown. At the Washington Peace Conference of 1921-1922, for example, the very real chance of war in the Pacific between America, Japan and Britain led to a world-wide revulsion against the very idea of Weapons of Mass Destruction, notably poison gas.

MacMillan spells it out: “Hitler did not wage war because of the Treaty of Versailles,” she argues, though it gave him an excellent straw man for his propaganda. “He would have demanded…the destruction of his enemies, whether Jews or Bolshevik. There was nothing in the Treaty of Versailles about that.”

Even Barbara Tuchman for all her stress on “disillusionment” was struck by the human attributes of hope and resilience that carried on in the throes of the Great War. “Men could not sustain a war of such magnitude and pain without hope – the hope that its very enormity would ensure that it could never happen again.” That hope may not have been fulfilled in totality, but she then adds how “the mirage of a better world glimmered beyond the shell-pitted wastes and leafless stumps – the hope that out of it all some good would accrue to mankind kept men and nations fighting” (pages 439-440).

Perhaps the greatest change of all.

Perhaps the greatest change of all.A Glimmering Hope

The boys who returned had their share of shell-shocked veterans all right. Yet an effective young Missouri captain named Harry Truman picked up a savvy that never left him as did Douglas MacArthur and George S. Patton after their first taste of real combat. Above all Americans had shown they could project power far overseas to the tune of 2,000,000 doughboys. And sustain them in the field. The temporary union of Big Business and Big Government had created a startlingly effective war machine ready to produce cars, vacuum cleaners and telephones galore in 1921, which it did.

In short 1921 showed we were, overall, a resilient and determined species. The League of Nations came out of the war and failed but led to the United Nations, keeping alive a sense of global values and norms. “The United Nations,” Winston Churchill later judged, “was not designed to lift us to heaven but to save us from hell.” Churchill as Colonial Secretary in 1921 signed a peace treaty between Britain and Ireland – another seeming impossibility.

Significantly, even America’s late entry into the war showed how self-blinded peace-loving democracies could be mobilized effectively in defense of civilized values. Millions responded enthusiastically to the call to “make the world safe for democracy.” Even for Tuchman some “dignity and sense” accrued to the War to End Wars. The hope for a better world did not die in the trenches. Fun and experimentation did not die in Flanders Fields. In 1921 RADIO station KDKA began in Pittsburgh and the first broadcast of a baseball game came from the Polo Grounds in New York. Few could see in those small beginnings an emerging technology that would enrich all of us culturally and psychologically. That tech revolution continues unabated.

Yes, history can be distressing sometimes but there are always thing happening to keep life hopeful. After 1921 came the Roaring Twenties. Let’s hope we will see our own high-stepping version before too long.