Before Genesis – The Pagan Worldview and the Biblical Difference

We gain a better perspective on Genesis 1-10 when we realize it was ‘debunking’ many of the ancient myths of the period

By Neil Earle

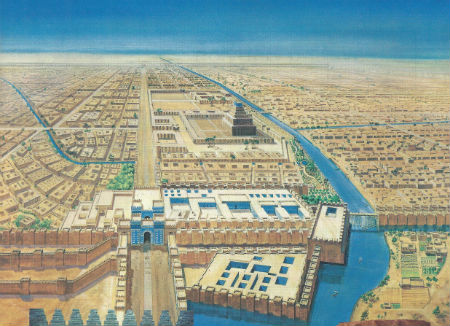

Prominent in ancient legends, Marduk's temple dominated ancient Babylon even as Bible writers treated it with disdain.

Prominent in ancient legends, Marduk's temple dominated ancient Babylon even as Bible writers treated it with disdain.Readers of the early chapters of Genesis are often not aware that the Old Testament accounts come late in the human story.

Scholars in the late 1800s uncovering tablets and remains from the area of modern-day Iraq and Syria were digging up records of what ancient people believed about origins – of mankind, of kingship and of the universe itself.

In particular the recovered Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh where the Babylonian hero purports to encounter a man who survived a worldwide flood was seen as an earlier account of what we call the Flood of Noah from Genesis. The hasty conclusion of this early generation of archaeologists was that the Bible was merely copying and mimicking earlier flood legends passed on by ancient peoples.

This became central to the skeptical conclusion that the Bible was a second or third rate production compared to what ancient peoples were doing.

This criticism has been answered by capable scholars working with the Old Testament who have advocated instead that the accounts in early Genesis are morally and philosophically light years ahead of what had gone before. The Bible writers were not just slavish “Johnny-come-latelys” but instead were passing on dramatic new, healthy, redeeming thought forms that would eventually influence a whole civilization, the Judeo-Christian way of thinking that was once so dominant in the North Atlantic region.

Bible History: A Psychological Turning Point

Popular historian Thomas Cahill has waxed poetic about the supreme difference between the historical/religious writings of the ancient Babylonians and Assyrians and the narratives carefully handed down about Adam, Noah, Abraham and Moses.“The anonymous authors of Gilgamesh tell their story in the manner of a myth. There is no attempt to convince us that anything in the story ever took place in historical time. At every point we are reminded that their action is taking palace ‘once upon a time’ – in other words, outside meaningless earthly time. The story of Gilgamesh like the gods themselves belongs to the realm of the stars…Time as we think of it was unreal: the real was what was heavenly and archetypal. For us, the heirs of the Jewish perception, the exact opposite is true: earthly time is real time; Eternity, if we think of it at all, is the end of time.”

Note Cahill’s stress on the difference with Israel’s chroniclers and historians: “They did their bests to be faithful to their tradition…there is in these tales a kind of specificity – a concreteness of detail, a concern to get things right – that convinces us that the writer has no doubts that each of the main events he chronicles happened. These are not, like Gilgamesh, archetypal tales with a moral at the end…If the stories of Cupid and Psyche or Beauty and the Beast never happened in real time, no one is the poorer for that. But if Abraham and Moses never existed, or if they did not recive their commissions from God, their stories have no point at all – nor do Christians and Muslims, who also count themselves as heirs of Abraham.”

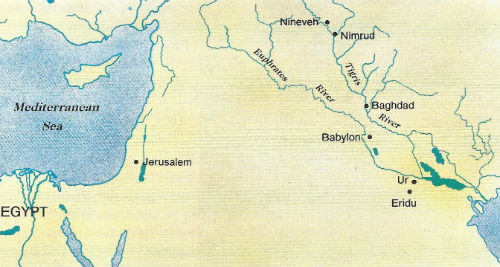

But these of course are fighting words. Even in the strange anomalies in Genesis such as talking snakes and 960 year old men there is a solid moral purpose behind them. The anomalies jump out of a text firmly embedded in history and even geography – the Tigris and Euphrates of Genesis 2 still exist, as do the place names Haran, Ur and Nineveh Province.

Gerhard von Rad said it years ago: The Hebrews and to an extent the Greeks are inventing history, serious chronicles permeated with a strong moral content. Cahill calls these accomplishments “one of the great turning points in the history of human sensibility,” and explains how a tribe of desert nomands (the Jews) changed the way everyone thinks.

The Pagan Worldview

Let’s look at a small sample of the founding myths and legends of ancient people in Mesopotamia and their key cities of Babylon and Nineveh. We will clearly see for ourselves how the Biblical writers are guided by a set of precepts and an approach to morality that far exceeds the pagan worldview it has replaced.

Consider some of these ancient misconceptions and false directions.

“The Wars of the Gods”

In an Assyrian tablet called Enumah Elish dating to the early 2000’s BCE we get the gist of it. “In this story the world was formed as the result of a cosmic war and people were created so the gods would no longer have to cook their own meals, or sweep out their own temples,” summarized Hoerth and McRay in Bible Archaeology (p. 42). Numerous other sources confrim this ancient tale of the gods and their foibles.

Ennuma Elish (”When on high”) goes on to add

“When on high the heavens had not been named…

Then it was that the gods were formed within them…”

Picture a flat Near Eastern landscape of mud and silt with a mist emerging on a nearly empty horizon. Out of this chaos came the first gods Apsu and Tiamat who bore others. These lesser deities were so noisy and bothersome that their parents decided to kill them. But…the minor god Ea engendered a son Marduk who destroyed Apu, then made war on Tiamat and her evil son Kingu. After defeating her Marduk cut the mother-god in two like a shell fish and placed one half to form the sky and the other below to form the nether world.

Man’s Ignoble Origin

Attacking Kingu, Marduk formed human beings from his blood for only one reason – to serve the gods…

“I will establish a savage, man shall be his name…

He shall be charged with the service of the gods

That they might be at ease.”

Clearly, the gods read about and sung about and worshipped before Genesis was composed placed little value on human beings. This premise violates the whole mindset of our Western approach to justice.

“Power vs. Justice”

To defeat the gods Marduk demanded absolute power after an assembly of lesser gods in an inebriated state. It is the absolute power of the ancient monarchs that still shocks us today with the claim that kingship was “lowered from heaven” when actually it was the rule of whoever was the strongest. People lived in stark fear of their rulers who claimed to be appointed by the gods who could kill off all their rivals.

There were reasons for absolute dictatorships to arise in the Ancient Near East. As Georges Roux has documented, on the flat Mesopotamian plains of Iraq and Iran armies of brigands could roam at will and power went to the warrior who could protect your tribal group. Survival and protection is everywhere recognized as the key virtue in this period and the strong man or most powerful god was the one who could protect you (Genesis 10:8-9). The King of Uruk is praised on a vase in god-like fashion: “When Enlil (a sky god) had given him the kingship over the nations…[he] made all the sovereign countries wait upon him, and made everyone from where the sun rises to where the sun set submit to him…All sovereign countries lay as cows in pasture under him” (Roux, p. 139).

We are not as far removed from these brutal top-down autocrats as we like to think. A concern for human rights is the exception rather than the rule in history and that very concept has strong and early Biblical roots, as we now see. Indeed, the Old Testament prophets delievered scathing unrelenting attacks on men making godlike claims. Notice Jeremiah 50:1-2, “Tell the news to the nations! Babylon has fallen! Her god Marduk has been shattered!” Isaiah wrote: “The emperor of Assyria boasts, ‘I have done it all myself. I am strong and wise and clever…But the Lord says, ‘Can an axe claim to be greater than the man who uses it?’”

This cradle of civilization is the backdrop for much of the more realistic action in Genesis.

This cradle of civilization is the backdrop for much of the more realistic action in Genesis.Healthy Old Testament Contrasts

The teaching behind Genesis 1-3 where an all-powerful Creator God banishes the chaos, takes delight in his creation, endows man with his own image in terms of morality and reason, communes with his creatures and even clothes them after they rebel against his main charge – this is as far removed from most Origin Stories of the Ancient Near East as can be imagined. The world before the Genesis worldview rested on a brutal governmental system too much like that encountered in modern movies such as “Mad Max” or “Transformers” where civilization has been destroyed and the Law of Might makes Right is back in vogue.

The creation account in early Genesis delights in a beneficent and kind God dutifully speaking his world into being and creating a biosphere to function for the well-being of his supreme work, humankind – and humanity as male and female bearing his image, an astonishing concept for the Bronze Age culture.

The ancients lived in the uncertain world of the Mesopotamian flood plain, region of violent and unexpected change – sandstorms that arise in an instant, cloudbursts that create instant seas of mud, frigid winters and scorching summers ruining many a crop. The only way it was felt to regulate this chaos was to meet under a strong Priest-King and petition the gods for relief and safety and, in George Roux’s words, “secure their goodwill by performing the age-old rites that ensured the maintenance of order, the revival of nature and the permanence of life.”

Ritualistic religion sprang up and some of had a softening effect as in these lines from a Babylonian “Counsel of Wisdom” urging

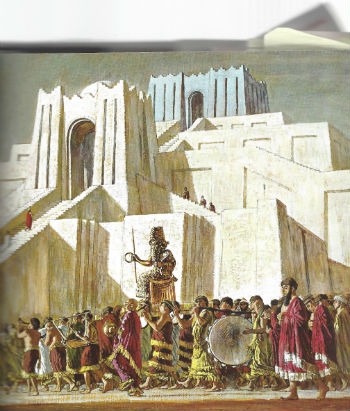

Worship was major in the Ancient Near East as a way of appeasing the chaos people saw about them.

Worship was major in the Ancient Near East as a way of appeasing the chaos people saw about them.“To the feeble show kindness,

Do charitable deeds; render service all your days…

Do not utter libel; speak what is of good report

Do not say evil things, speak well of people…”

But much religion was ritualistic and programmed and some of it was stern indeed. But only by appeasing the gods – sometimes through blood sacrifice – could the king and the peasants feel the Chaos would be held at bay for another year.

In short, there was little concept of the value of choice, of a beneficent Deity allowing humans to make their own decisions and accepting the consequences. The expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, the Cain and Abel narrative, the appeals of Noah to the Flood generation to change their ways – these early accounts in Genesis are the seedbed of our ideas of right and wrong, of justice and punishment, of reward and retribution and most especially of a Just God who is totally different than the frightening bully-gods of the Near East or the foolish immortals of the Greeks on Olympus choosing sides against each other in the Trojan War.

Measured against the world that was in vogue before Genesis, the inspired author was moved to relay a clean, high quality, even exalted account of the One “who spoke and it was done,” who instituted the first labor legislation (the weekly Sabbath) and forbade the senseless shedding of blood.

The difference is stark. Perhaps you haven’t seen it that way before but why not read these wondrous early chapters from Genesis 1-11 for yourself and then see how God sets out to redeem his straying creation with the call of Abraham and Sarah. Read on. It will make for a refreshing experience.