Chapter Thirteen: ‘A National Treasure’

“For years the Maple Leafs were a glittering national treasure,

as Canadian as prairie wheat fields and lonely northern lakes.”

– William Houston, Maple Leaf Blues

The New York Rangers. The Boston Bruins. The Montreal Canadiens. Hockey legends were coalescing as the 1920s turned into the 1930s. It was time – high time – for Toronto to step into the action.

In Toronto, Conn Smythe’s Irish luck had held. Although it wasn’t New York, the city on the northern edge of Lake Ontario was taking off fast.

People had money to spend and they spent it. The lead and zinc mines of the Canadian Shield were helping finance the new corporate towers along Bay Street in Toronto.

And Smythe was ready to go at last. After playing in one of the last big war-time hockey games in Toronto, he had gone to France, taken part in the bloody six-month campaign in the Somme in 1916 and the Canadian assault at Vimy Ridge the next year. Like most Canadians of his generation, his patriotism was real. The Maple Leaf they wore on their epaulets was, for them, a cherished symbol.

No Holding Back

As a leader and an innovator, Connie was as adept on the Western Front as he was on the ice fields of Ontario. Once, going down a road under heavy shelling to bring up more ammunition for his battery of big guns, Smythe decided to detour around the trail the British had built.

“My men, Hamilton and Orillia fellows, were used to playing hockey and football and coping with situations as they come,” he proudly remarked.

Conn earned his Military Cross by being in the thick of the action as a forward artillery observer. He jumped into a German dugout and killed three of the enemy before fighting his way back with some wounded New Brunswickers. After cursing out a superior officer for allowing two comrades to die untended in an open field, Smythe transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, where he got himself shot down and ended up spending fourteen months shuttled from one German prison camp to another.

Released, he returned to Toronto to marry his teen sweetheart, Irene Sands. With his accumulated army pay, he bought a lot on Lawrence Park subdivision, attended the University of Toronto and became a partner in a small construction firm. On January 27, 1920 he ordered a five-ton “National” truck with a hydraulic hoist. He painted on the side: “C. Smythe for Sand.” That is, when he wasn’t playing hockey or coaching new teams.

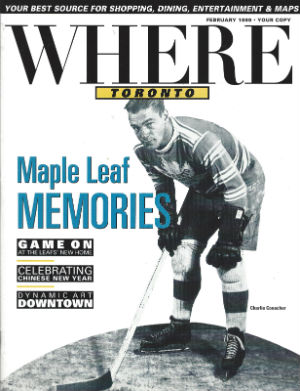

Charlie's clean-cut image set a tone.

Charlie's clean-cut image set a tone.Smythe’s Vow

Prison camp had not helped Smythe’s skating ability. His hockey-playing days were fading. Yet more and more, he was called to coach and manage local Toronto teams, mostly intercollegiate squads.

“Almost every night after close of business in the sand pit, I was out coaching or scouting other teams,” he remembered.

In 1924, on a trip to Boston, Conn started a lifelong feud with an old Patrick acquaintance named Art Ross. Ross was coaching the NHL’s newest franchise, the Boston Bruins. Smythe’s irritating claim that his Varsity team could beat the Bruins anytime, anywhere was vindicated in three victories before packed games at the spanking new Boston Gardens.

This was carrying it to the Yanks with a vengeance. Vowing he would bring Toronto a Stanley Cup within five years, Smythe set out to turn the struggling Toronto St. Patricks into a major league team. They were, by 1927, still Toronto’s only presence in the NHL. When an offer came in from Philadelphia to buy the team for $200,000, Smythe saw his chance. He launched a publicity campaign to keep the team in Toronto. Rounding up investors to meet the bare minimum $160,000 needed to keep the St. Pats in Toronto, Smythe shelled out $75,000 for the team on February 14, 1927. The other $75,000, he promised the creditors, would follow in thirty days.

Birth of the Maple Leafs

The next day, February 15, the Toronto Globe headlined: “Goodbye, St. Pats! Howdy, Maple Leafs!”

As Smythe would later write in his autobiography: “I had a feeling that the new Maple Leaf name was right. Our Olympic team in 1924 had worn maple leaf crests on their chests. I had worn it on badges and insignia during the war. I thought it meant something across Canada.” He was right.

A national institution was being born. The irrepressible, pugnacious Smythe had been working for this for a long, long time. In an era when the Lord Stanley prize was “America’s Cup,” it was time for Toronto to weigh in as a major hockey force.

As an example of the intimate, personal style of team ownership then extant, Smythe led and managed the 1927-1928 Leafs. He would anchor the team around a stern, hardworking former pharmacy student at the University of Toronto named Clarence “Happy” Day.

In the summers, “Hap” Day would work for Smythe’s cement business and, in the winter, he would be the backbone of the Leaf team both as captain and handyman on defense. To “Hap,” Smythe confided his dreams of a hockey rink in the grand style, one that would be the talk of the NHL. It was clear, with New York ensconced in the legendary Gardens, Boston coming on strong and Detroit and Chicago not far behind, that Canadian teams needed bigger gate receipts to be able to buy and hang on to the best players.

Yet Smythe would have to be resourceful to finance his stately pleasure dome. Undeterred, he went to work with a will.

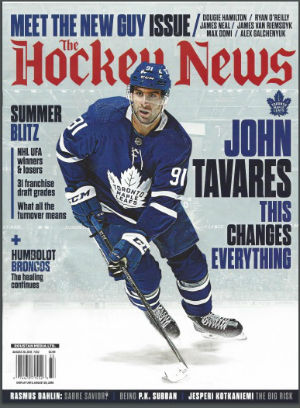

Tavares did make a difference – but not enough.

Tavares did make a difference – but not enough.“Everything New and Clean”

Smythe could sense that the sport was changing. It was becoming a major part of people’s off-work lives, something deeper than just entertainment, something binding people together in a collective feat of the imagination as they projected their fan loyalties on athletes engaged in one of the toughest contests imaginable. Smythe would expound on this theme to anyone who would listen. He knew the old Mutual Street Arena’s 9,000 seats could not compete with the booming movie theatres as a place for a nice evening out.

“We need a place where people can go in evening clothes, if they want to come there from a party or dinner,” Smythe explained. “We need at least 12,000 seats, everything new and clean, a place that people can be proud to take their wives or girlfriends to.”

The Great Depression was getting meaner and yet Smythe estimated he needed a million dollars, perhaps a million and a half, to build his northern Xanadau. His racing friend and fellow Leaf director Larkin Maloney was supportive.

The two entrepreneurs visited the Montreal architect firm of Ross and MacDonald, builders of that Toronto landmark, the Royal York Hotel. They persuaded Sun Life to back the project for a half million. This allowed Smythe to win the support of the Bank of Commerce.

Maple Leaf Gardens Limited was incorporated on February 24, 1931. The T. Eaton Company was persuaded to sell its land on the corner of Church and Carlton, a mere block from the strategic Yonge Street streetcar line. Eaton also agreed to buy some Garden stock. Lobbyists Frank Selke and player Ace Bailey were peddling stock and persuading small businessmen to invest.

June 1, 1931

On June 1, 1931, bulldozers were ready to level the tobacco store on the corner of Carlton and Church, about a hundred yards from where Conn Smythe was born. But Smythe had to clear a major hurdle first. He was still a few hundred thousand dollars short.

“That wouldn’t be much today,” Conn recalled in the 1970s. “Early in 1931, it was a mountain.”

Smythe’s aide-de-camp, Frank Selke, had already mortgaged his house to buy $4,300 worth of stock. An idea took shape: could the workmen be persuaded to cut direct labor costs by taking 20 percent of their pay in Garden stock?

The canny Selke was dispatched to the weekly meeting of the Toronto Labour Council. His appeal – especially his admission that he had mortgaged his house to pay for stock – helped convince the union.

The idea that 1,300 Toronto labourers would find steady work for the year was also attractive. The world was truly younger then. The workmen could sense in Smythe and his pals the kind of “can do” hustle and industry that echoed their own dreams of success. The labor leaders came through. The project was on. Years later, Smythe never forgot the key role played by the unions in the fulfilling of his dream. It was “the final laying to rest of the feeling among some people that it was a crazy idea.”

“Happy Days Are Here Again!”

It was a fine populist moment. The Bank of Commerce joined forces with Toronto working men as Smythe and his team propagandized and hustled stock. The contractors, Thomson Brothers, were actually losing money on the deal but gamely carried on. When a Smythe competitor discovered this, he tried to persuade the banks to call in three Thomson Brothers notes to end construction and embarrass Smythe. But Conn covered for the company and his dream palace was officially opened on November 1, 1931.

The bands of the 48th Highlanders and the Royal Grenadiers marched out on the ice to the tune of Happy Days Are Here Again! This was two years before Presidential candidate Franklin Delano Roosevelt made it his own Democratic Party anthem. It was a scene, Smythe would later indicate, snatched from his rosiest dreams.

“A lot of the people were in evening dress, including our twenty-two Gardens directors...,” he fondly recalled. “But up in the capacity crowd of 13,542 among the people who tried to drown out Gardens’ president Jack Bickell’s speech from centre ice with cries of ‘Play hockey!’ were hundreds of men who had built the place and pawned shares in it.”

That spring, the Leafs would win the Stanley Cup before crowds of up to 15,000 people, most of whom would cheer themselves hoarse in a building that would soon become famous from coast-to-coast. Canada’s Team was here in force! And they were Conn Smythe’s kind of guys – unspectacular, hard-working, dependable, possessing a rough-hewn sense of honor and loyalty, born leaders and team players. They were living rebukes to his humiliation at the hands of the Tex Rickards, who preferred style over substance.

The “Kid Line”

Smythe already had Red Horner, “the greatest body checker I ever saw.” He picked up goalie Lorne Chabot from the Rangers. In bringing up Charlie Conacher (younger brother of Lionel) from the minors, Smythe gave the Leafs their first glamorous high-scoring squad, the “Kid Line,” which included Conacher, Joe Primeau, and Harvey “Busher” Jackson.

The “Kid Line” scored 792 points in seven seasons, beginning in 1929-1930. The lanky Conacher led the league in scoring for five years. He notched four 30-plus goal seasons from 1930-1931 to 1934-1935. In 1932, he scored five times in a game against the New York Americans and was instrumental in Smythe’s first Stanley Cup win in the spring of 1932.

Day and Conacher would be emblematic of a Leaf tradition – the low-key, relatively clean-cut (at least in public) young athlete with a ferocious loyalty to the team and a sense of civic example. They would be ever mindful of their influence on young hockey fans in particular. This civic spirit, a holdover from the days of noblesse oblige, fitted Toronto’s WASP ethic, its proud city-state mentality, its well-developed sense of itself as the arbiter of Canadian culture and mores.

The Public Spotlight

There was also this: a tart-tongued but idealistic press corps kept sports figures accountable in highly literate Toronto the Good. There was a strong sense of social responsibility.

This was the heyday of Damon Runyon, Ring Lardner and E. Grantland Rice, scribes who could point toward a moral or adorn a physical game with the nimbus of heroism or tragedy. In Toronto, hockey players like “Hap” Day and Charlie Conacher set a public-minded tradition that would carry on down through Ted Kennedy in the 1940s, George Armstrong and Bob Pulford in the 1960s, and Darryl Sittler in the 1970s. These were strong, decent men not averse to throwing the hard body check, but who also conducted themselves with decorum. This would be a Maple Leaf ideal.

At least most of the time. Conn Smythe himself always felt he was too excitable to be a good coach. He was probably right. Nothing showed the menace always lurking below the surface in ice hockey as much as the incident involving Ace Bailey and Eddie Shore.

Night of Infamy

It was one of hockey’s dark moments. Eddie Shore was by now the hard rock defenseman for the Boston Bruins – the Ty Cobb of hockey, goaded on by the competitive Art Ross. Ross and Smythe were bitter rivals.

“To understate the case, they hated each other,” quipped Joe Romain.

The rivalry between Smythe and Ross was the setup for professional hockey’s nights of infamy. It happened in rowdy, tumultuous Boston Gardens on the night of September 12, 1933. Out of it would come a new institution – the All Star game – and a living parable of the need to try to master the menace that emerged Caliban-like at unexpected times.

It happened like this… Ross had guided his Bruins to the Stanley Cup in 1929. They would repeat their triumph in 1939 and 1941. The Bruins had heart and desire and, most of all, hard-rock Eddie Shore, “Mr. Pugnacious.” Eddie was the most fearsome defenseman of his day and the darling of the Boston fans. Later on, the outspoken commentator Don Cherry labeled him “the Darth Vader of hickey.” Smythe had Ace Bailey, a fine stick-handler, and, according to Smythe, “one of the smoothest men in hockey.” But the two were only stalking horses for the real conflict, the rivalry between Ross and Smythe. Their teams were always in danger of becoming unglued when they played each other, as they did on December 12, 1933.

That night, Toronto’s “King” Clancy doled out a fierce check to Shore, who spun over Clancy’s knee and ended up dazed on the glass. Then, as Clancy headed for the Boston end with the puck, Bailey, who had switched to defense, skated back towards his own blue line to “cover” on the play. Shore, apparently mistaking him for Clancy, piled into Bailey from behind with a check that sent the Leaf player flying through the air and landing full on the head. He writhed uncontrollably, then lay deathly still.

Shore, still dazed from Clancy’s check, was hit clean on the chin by another Maple Leaf player and was sent sprawling to the ice, blood pouring from his head. As Smythe related the incident:

Then there was another face-off. Ace won it again and stick-handled for a while before he shot it into the Boston end. Eddie Shore got it and started up the ice. Clancy met him, knocked him down, and took the puck. As Shore got up, Bailey, still puffing from his previous one-man show, was just in front of him. George Hainsworth in the Toronto goal had the best view of what happened next – and he said Shore charged Bailey from behind...

Then Conn Smythe’s human nature got the better of him. He later said:

I remember saying right then to Conacher: “Somebody should do something about this, Charlie.” As he moved away, gripping a stick and a look of fury on his big, tough face, something happened that made me glance away, and the next thing I heard was a hell of a yell and there was Shore on the ice, bleeding all over!

“My God,” I thought, “Conacher has gone out and killed Shore – and I sent him!”

But Conacher didn’t do a thing. Red Horner was the culprit. Smythe continued his narrative:

“I couldn’t stand it, boss,” Red later told me. “I let him have one.”

It was one punch. Don’t ever say a good man who knows how can’t land a good punch while on skates...

The crowd came down from the stands when Bailey and Shore were being carried off. I was trying to fight my way through to go with Ace when some fan – I later learned, the hard way, that his name was Leonard Kenworthy – started pointing at Ace and yelling: “Fake! Fake! The bum’s acting!” I hit him flush on the nose and broke his glasses. For that I got arrested, taken to jail, and didn’t get out and over to where Ace was until about 2:30 in the morning.

The Career Ender

The nasty incident ended Ace Bailey’s career, got Horner suspended for three weeks, provoked a league enquiry and ended in Shore’s suspension for sixteen games. Smythe had to pay $200 in damages to Leonard Kenworthy, Esq. It was worth it, he always claimed later.

But then something else, something deeper and more profound began to take over. The near-demise of Bailey had shook hockey’s founding myth of innocent days on the pond. League President Frank Calder moved astutely to protect professional hockey’s reputation. He urged the Leafs to host a benefit game for Ace Bailey with the highlight being a public reconciliation between Bailey and Shore at center ice.

The Hug at Center Rink

The first NHL All-Star Game was born. It was conceived as a public relations stunt for the good of the game. Appropriately, it took place on Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1934.

“Before the game, Shore and Bailey met at center ice,” Smythe later reminisced. “The crowd was silent as the two faced one another for the first time since that crushing check. When they hugged one another, there was a huge roar of release from the crowd. Bailey, as fine a gentleman as ever lived, said he knew the result of that check had been an accident. But he never played hockey again.”

The handshake between Bailey and Shore, the remorse, the accepted tribute, all done before a cast of tens of thousands… This was superb spectacle. It showed how hockey resonated with the still mostly male credo of “play hard, play fair, and if you do some dirt, ‘fess up and shake the other fellow’s hand.’” It was a rough-hewn, personal code for rough-hewn owners and players.

The Ace Bailey Benefit showed that hockey had the potential to transcend its origins in the ice forge. Something reminiscent of the game of Hughie Murray remained. The Gardens, the crowd, the teams themselves had clearly become greater than the sum of their parts. The game was being transposed into a carrier of something cultural, a ritual container for a Code of Manliness that had a rough justice about it, not unlike life itself in the timber runs and mining camps where the game was shaped and weaned. Here was professional hockey offering a public morality play in which the rhythms of real life (Bailey’s injury) and the suspended plausibility of street theater (Shore could hardly refuse to offer public reconciliation with the NHL against him) began to mesh.

A Dent in “a Field of Honour”

Beyond the sweating athletes, the punishing and calculated violence, something almost indefinable was shining through. The maxim that “life is a field of honour” didn’t quite fit. Eddie Shore would continue to be an almost manic competitor. But February 14, 1934 was a clue to how ice hockey reflected and strengthened some core social norms. Something embodied in the word “civility.”

It was a loaded pause in the time of heroes, a romantic echo of a time when single combat warriors exchanged pleasantries after face-to-face conflict. There are still hockey fans alive today who remember hearing of this. David Bacon, a Toronto-born journalist working in Vancouver, told our senior author: “My grandfather was there the night Ace Bailey and Eddie Shore shook hands.”

Big league organized hockey, warts and all, with its strange catch-as-catch can intermeshing of the real world with fantasy – the money game, some would call it even at this stage – possessed the capacity to arouse often-submerged notions of honor, fair play and the glorious intangibles that, perhaps, are ritual reenactments of life lived on a higher plane. Perhaps even the ghost of Matthew Arnold might have slept more soundly if he could have seen the taming, at least temporarily, of those two roughs, Bailey and Shore. But here it was, in the House Smythe Built, a living parable of the competitive capitalism forced to bow to the dictates of Ralph Connor.

A Public Parable

These codes of chivalry would surface one more time in the 1930s.

After two consecutive Stanley Cup wins in 1930 and 1931, a long drought set in for the bleu, blanc et rouge. Morenz was traded, then brought back again to spearhead Les Canadiens.

On January 28, 1937, the Canadiens were locked in furious combat with the Chicago Blackhawks. Morenz was skating in on the goal when Chicago defenseman Babe Siebert dove headlong at him from behind. Morenz’s skate blade wedged into the grain of the end board, trapping his legs just as Siebert’s full weight came down upon him.

Morenz was confined to the hospital with multiple fractures to his legs. There, on March 8, he apparently died of a virus. Montrealers were stunned. The sombre old post of Maisonneuve and the liquor town of the coureurs de bois witnessed few spectacles like that which gripped the Forum some days later.

Funeral services were held at center ice as 25,000 fans, many in tears, showed up – a full 7,000 more than had appeared at that Saturday night game. They filed by to pay their respects to one of hockey’s first superstars.

Even Dandurand was surprised. Obviously, his squat ice palace on Rue Ste. Catherine was becoming more than an arena. Beyond the financial deals, the player trades, the free-wheeling excitement of firewagon hockey, beyond all that was the ordinary fan’s ability to personalize things, to invest the common icons of skates and sticks with something transcendent, perhaps the idealism and wish-projection that had clothed the Canadiens in the nimbus of heroism. The Montreal Forum and Maple Leaf Gardens possessed the potential to become a site of transcendence, ice cathedrals for the reckless exploits of rugged men and their fans caught up in a specially marked off time and space, a place reserved for the time of heroes.

References Cited

David Mills, The Blue Line and the Bottom Line: Entrepreneurs and the Business of Hockey in Canada, 1927-90.

Brian McFarlane, 50 Years of Hockey: 1917-1967. New York: Pagurian Press, 1967.

Conn Smythe, If You Can’t Beat ‘Em in the Alley.