D-Day and the Defense of the West

By Neil Earle

For those who follow historical commemorations it is somewhat surprising how much attention the 75th anniversary of D-Day this June 6 is generating.

I remember an English widow protesting tearfully to a TV reporter in 1984, the 40th after the event: “It seems everyone has forgotten. Like he died in vain.”

Grief is understandable but this hardly seems to be right.

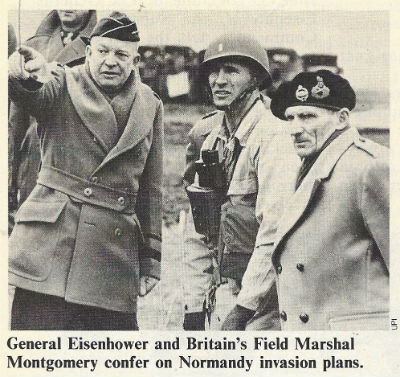

President Barack Obama made a memorable visit to the Normandy beaches for the 65th anniversary in 2009, conjuring echoes of Walter Cronkite’s 25th year tour of the beaches with Dwight Eisenhower, the commanding general on June 6, 1944. Clips of Ronald Reagan’s 1984 visit to Point de Hoc where the US Rangers faced murderous fire to scale the cliffs at Omaha Beach play well in history lectures even today.

All this seems to moderate the chant launched some time back by radical students: “Hey, hey, ho, ho; Western Civ has got to go.”

By a feat of irony it was in 1984 that William Manchester published his first volume of his Winston Churchill biography in which he saluted that World War II/D-Day generation of leaders by staying: “And so he defended Western civilization at a time when men felt it was worth any sacrifice.”

President Reagan echoed that at Omaha beach in 1984 when he offered the answer to his rhetorical question “Why? Why did you do it?” he answered his own question: "When we look at you we know the answer. It was faith, faith and belief and loyalty and love and the deep knowledge that there is a profound moral difference between the use of force for liberation and the use of force for conquest.”

Today, it seems, Western civilization is not rated as highly as it was in 1944. Outspoken conservatives are perhaps right when they lament the over-fixation on a Past where racism and sexism and their attendant evils leavened the culture. The Future, however is unknown and the Present uncertain. The Past can be a source of instruction if we remember what those young Allied troops were to encounter as they marched across Europe from 1944 to 1945. At the Nazi death camp in Dachau, General Eisenhower ordered the town leaders to tour through the premises, holding their noses as they went. Here was the basement of what Western civilization had come to. Meanwhile the British and Canadian forces had arrived in the nick of time to prevent massive starvation in Holland.

The Dutch were living on tulip bulbs and they’ve never forgotten the lads who drove into their towns and cities in their Sherman tanks radiating a spirit of help and hope.

There are thus obvious reasons why so much hinged on Allied success at D-Day.

A failed invasion would have delayed the liberation of Western Europe for months perhaps giving Hitler time to strengthen his eastern defenses against the advancing Red Army. Time too, to perfect more of his “super-weapons” such as the dreaded V-1 and V-2 rockets that began to rain on London a mere week after the Allies splashed ashore on June 6, 1944. Many more prisoners of war and Jewish hideaways would have died. War-weariness was even setting in back home, where anxious mothers and sweethearts sat next to their radios trying to catch the news from the front that early summer of 1944.

Everyone knew the Allies were coming and that battles far greater than Gettysburg or Waterloo would be fought.

President Franklin Roosevelt, not an overtly religious man, struck the exact mood for his people when he announced the invasion on the nation’s radios. “Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation,” he began, “this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.”

There it is again – that word, civilization. The same word Churchill had used when he had summoned his people to defend the realm against the threat of Nazi invasion in 1940: “Upon this battle depends the survival of Western civilization!”

Both men had lived a lot and seen a lot. They knew that Judaeo-Christian culture had major flaws but also had its own built-in self-corrective dynamics – from Magna Carta to the United States Constitution. There were means for reforming the most obnoxious offenses.

“They fight not for the lust of conquest,” Roosevelt said of these young men just then hunkering down on the bloody beaches or moving inland, “they fight to end conquest. They fight to liberate. They fight to let justice arise, and tolerance and good will among all Thy people. They yearn but for the end of battle; for their return to the haven of home.”

This is great public oratory, for sure, but obviously it was a lot more. Former President and General Eisenhower told Walter Cronkite on that return visit to the beaches in 1969 that those young men who died, those young men he had to send into the onslaught, they gave us another chance, another chance to get it right.

One feels sometimes when eyeing the strife in Venezuela or the callous terror bombing of civilians in sundry spots around the world or even our own churches and synagogues that the call to set free a suffering humanity is a big task, perhaps too much for any civilization to fulfill. But through events like the men who sacrificed their all at D-Day we keep getting a chance to do it right, to correct what is wrong and move on in the hope that animated so many boys who died on those beaches, on June 6, 1944, the day called “D.”

(Neil Earle teaches history for Grace Communion Seminary.)