Above and Beyond: The Joe Ogonowski Story

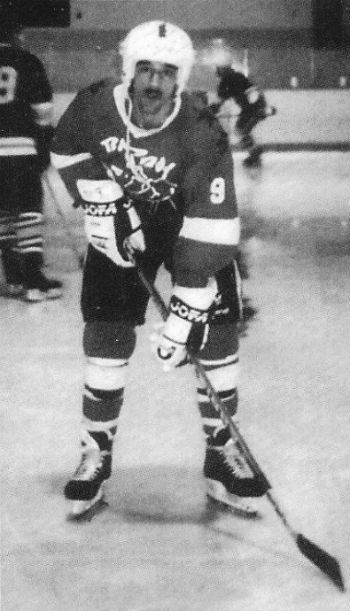

Joey Ogonowski in happy pose.

Joey Ogonowski in happy pose.(Co-author Gordon Lore wrote this piece for the Hereditary Neuropathy Foundation Newsletter N 27 of September 1995. It previously appeared in the May/June 1995 edition of “For Patients Only” magazine under the title “For Dialysis Patient Joe Ogonowski, Teaching Others to Skate Through Life Isn’t an Option, It’s a Crusade.” In light of the higher-profile illnesses of NHLers Bobby Orr, Bobby Clarke and Mario Lemieux, it makes an interesting answer to the question – “What kind of people play hockey and why?” Joey “O” also serves as an archetype for those athletes who unselfishly serve and inspire their communities.)

It had been a great year for Joe Ogonowski, 34. In March and April, 1991, as captain, he led his central New Jersey-based ice hockey team, the Bad Boys, to a gold medal victory at the Atlantic District Championships in Trenton, NJ. Two weeks later, they brought home the gold again in their third try at the Can-Am Tournament in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. There they played a grueling five games in two days in which 49 other teams also competed.

Not bad for a guy on dialysis who has lived with the threat of kidney disease all his life. One of his brothers, Bob, is also a dialysis patient. Another brother, Jimmy, died of renal disease. So did his grandfather, in the 1940s, before dialysis was even an option. While his mother, who died in 1983, wasn't stricken, she was the carrier of Alport's Syndrome, a hereditary kidney disease in which, in some families, males are more severely and frequently affected than females. This was certainly the case in Joe's family. He's concerned that his son, Joey, 2, will inherit the disease, and his daughter, Gina, 3, will carry it like his mother. So far, however, both children have tested negative.

The Early Years

Ogonowski and his brothers were raised in Newark, NJ, in a neighborhood he claimed was controlled by the Mafia. Then, after the riots and fires of 1968 following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., “my father wanted to get us out of there.” They moved to the town of Brick, close to the Jersey shore, not far from Atlantic City.

Joe admits that “growing up was pretty crazy.” In 1975, at the age of 19, his brother, Jimmy, was stricken with kidney disease and was forced to go on dialysis. At the time, Joe said, each treatment lasted about eight hours. But neither Jimmy nor the rest of his family were prepared.

“My parents were having problems, and, when my brother got sick, we were hoping that would bring them closer together, but it had the opposite effect,” Joe said. “Jimmy didn’t go to a lot of his dialysis treatments. He came home with band-aids on this arm [to make us think he had gone to his treatments]. He would drive around or go somewhere for eight hours. He was a real troubled patient and didn’t follow his diet or listen to his doctor. My parents really didn't realize what was going on.”

Two years later, Jimmy, who was only 21, died. Joe's other brother, Bob, was also only 19 when he contracted the disease and went on hemodialysis in 1981. Unlike Jimmy, Bob is doing well because, from the beginning, he followed the proper regimen and stuck to his diet.

Joey's Bad Boys, winners rampant.

Joey's Bad Boys, winners rampant.“Just a Matter of Time”

Ogonowski said that, for years, he had not really faced the fact that he would probably join his brother as a kidney patient.

“It was just a matter of time, but I was so thick-headed that I believed it wasn't going to happen to me,” he stated. “I thought that, by going to Jack Lalanne’s gym three times a week and playing as much hockey as I could, I would somehow physically beat it.”

In 1988, however, Joe was forced to face the inevitable.

“I remember working with Bob spray-painting fences,” he explained. “I couldn’t even squeeze the trigger of the spray gun because of the cramps. I even got a cramp in my neck that interfered with my breathing. It was the second time that happened, and it really scared me.”

Joe went to see Bob’s doctor.

“His doctor wanted to put me in the hospital right away because my blood pressure was sky high – 210/190,” he remarked. “The potassium count was high as well. He said I could stroke out anytime and that I should be dialyzed as soon as possible. I checked myself into the hospital the next morning.”

After a rough first year battling high blood pressure and searching for the right combination of medication to keep it under control, Joe began to settle into the dialysis routine. Now, he travels from his home in Lakewood, NJ, to the nearby outpatient dialysis unit at Brick Hospital for his treatments three times a week.

“But It's Hockey...”

But it’s the roughhouse game of ice hockey and the loving support of his family that are the rock-solid components of Joe Ogonowski’s post-dialysis life. He's been playing since he was a youngster in 1971. For the first 15 years, he was goalie. In high school, he met Jimmy Dowd, who, while still in school, was drafted to play with the New Jersey Devils. They became friends, and Dowd went on to do well in the big leagues. Then, after an interlude of not playing at all, Ogonowski was motivated to return to the sport. Now, he skates in the forward position.

Ogonowski captains the Bad Boys, a semi-pro team in the Senior A Men’s League. During a typical season (October-March), they play a 25-game schedule with at least two practice sessions a week thrown in.

“I Coach Peewee”

Between seasons, Joe said, “I coach Peewee”—kids around the age of 12 or thereabouts—every week about eight months of the year.

“The kids are great and I can forget about [my other problems] then,” he enthused. “They don't look at me as a dialysis patient. They call me Coach Joey-O.”

Ogonowski said the kids he coaches have their own team and average two games every weekend traveling throughout New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, and Canada. And he’s proud of his young charges. Recently, they placed third in the state championships in Wall, NJ, and even played at the West Point Military Academy in New York.

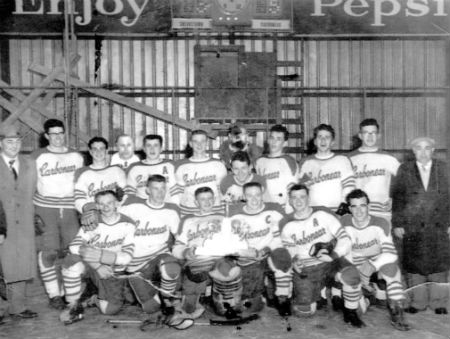

Carbonear champs: Sometimes local hockey says it all – Editor's uncle

(top left) with 1958 hometown team.

Carbonear champs: Sometimes local hockey says it all – Editor's uncle

(top left) with 1958 hometown team.Power Skating

Joe also gives hour-long power skating lessons and referees hockey games “on the side.” Power hockey skating concentrates on the legs.

“It's part of conditioning,” Ogonowski explained. “It also keeps me in shape. At the same time, I’m helping some kids. A lot of parents I've met want me to teach their kids.”

He has about 30 of the “kids” who range in age from three to 50.

Joe admits that being on dialysis does change his playing habits somewhat: “I was really playing good hockey right before I got sick.” He tried to keep up with his friend, Jimmy Dowd, but couldn’t.

“A Rocky Road”

“I was really out of it,” he remarked. “I had trouble even getting up the stairs. It took me about two years to get back to playing where I am now.”

At times, he now feels he’s playing almost as well as he did before dialysis: “It’s such a rocky road. One day you feel OK, the next day you don’t. It’s a real head game.” It's a sentiment any dialysis patient can identify with.

Except for a broken nose he sustained in a Garden State Games contest, Joe has suffered no bad accidents or untoward incidents.

“I just thank God I can still play,” he stated. “When I see a person who has lost a lip or a limb, I think I don’t have it bad.”

Joe would like to play professional hockey, but believes his rather advanced age for the sport as well as kidney disease will preclude him. Nonetheless, he’s looking forward to the day when he gets his transplant, so “I can go back into hockey full-swing and really play a hard game. Now, it’s really frustrating because I know how well I can really play. I play well now, but I know I could do better.”

It could well be that his son, Joey, will take up the challenge. At the age of only two, he’s already handling the hockey stick.

“A Blessing in Disguise”

Ogonowski met his wife, Dawn, 24, when he first started dialysis, and “she was a blessing in disguise.” She was a friend of his step-sister. They started talking on the phone when he was in the hospital. Then they began to date.

Dawn came along at a time when Joe needed her the most. At first, except for some warning words from his brother to follow his dialysis regimen religiously, she was his entire support group, a positive guiding force. When he felt depressed and didn’t want to go to treatment, she really pushed him.

“She puts my needs and feelings ahead of hers every time,” he said with enthusiastic affection. “I don't know if I could do that. I’m grateful for her. She really keeps me going, and I don’t thank her enough.”

Joseph Ogonowski Obituary

Date of Birth:Saturday, April 15th, 1961

Date of Death:

Monday, April 14th, 2014

Official Obituary:

Joseph (“Joey O”) Ogonowski passed away Monday, April 14th, 2014 in Port St. Lucie, Fl. He was 52 and survived by his wife of 23 years Dawn, daughter Gina 22, son Joseph 20, and daughter Jazmine 16. He was preceded in death by his mother Mary Jean Agosta, his father Robert Ogonowski, Sr., and his brothers James Ogonowski and Robert Ogonowski, Jr.

He was the owner of “Joey O and Son Painting” and “Cheery O’s home services.” He had his level 5 ‘Masters’ certification in ice hockey coaching. He was an ice hockey referee and skating teacher for 25 years. The hockey communities of South Florida and the Jersey Shore will never be the same.

There will never be another Joey O.

Advice to Patients

Advice to patients? Joe has plenty. It’s a crusade he places right up there along with teaching hockey to kids. He’s even written a short treatise—Dialysis: A Patient’s Guide—with the help of the Brick Dialysis Center, a component of the Medical Center of Ocean County. Joe hopes to go on the patient lecture circuit and tell all his fellow patients not to do what both he and his brother, Jimmy, did. But he was lucky. He’s still alive, even after a stroke in which he almost didn’t make it.

From the Guide: “Since I had that stroke, I look at life totally differently. Many of the problems... could have been avoided if I had taken my doctor’s advice. I got so tired of going in and out of the hospital that year... A doctor isn’t a mind reader. He doesn’t know what’s wrong unless you tell him... Any sickness can turn into something major for a dialysis patient, so it’s important to be honest with your doctor.”

“Getting to Know Your Machine”

Joe writes that “getting to know your machine is very important. The same nurse isn’t going to put you on every treatment.” He says there are even classes that patients can attend to learn more about their machines. He was lucky. His doctors encouraged him to know more about that hunk of computerized metal that he spends so much time with and that, literally, keeps him going through life.

“Remember,” he cautions, “you lost your kidneys, not your brains. It is in your best interest to know exactly what is happening during your treatment.” And “having a good relationship with your doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals will only make dialysis easier for you.”

“Light at the End of the Tunnel”

Above all, Joe reflects on his brother, Jimmy, and the guilt his mother felt when he died, knowing she was the carrier of the disease that caused her son’s all too premature passing, of his parents’ separation and his own brief descent into drugs following that family tragedy.

“If only Jimmy had someone to tell him that things would get better and that there was light at the end of the tunnel...,” he reflected. “I’d tell patients that their lives are not ending. They can start a new life.”

Or make the ones they had even better. “Music has charms,” the wise man said; apparently, for Joey O, so did hockey.

(Gordon Lore's latest book "Connections" – a sizzling new biography of famous celebrities he has met – is available from Bear Manor Media and Amazon.)