Pop Culture Reflections on “Hillbilly Elegy:” A Hurting Heartland, Then and Now

By Neil Earle

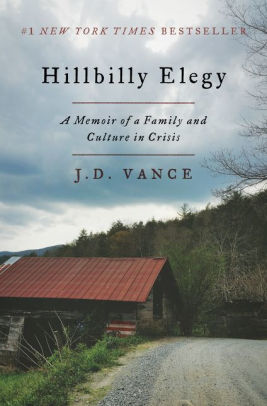

“Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis” is J.D. Vance’s well-received confessional of his growing up in rural Kentucky and small-town southern Ohio. It largely focuses on those Americans left out of the rush to prosperity in the age of globalization, an era now seen as having peaked. Some of it makes for harrowing reading indeed. In essence it is a calm critique of both right wing and leftist policies that have created what he feels is a costly divide between what he sees as two separate worlds, the upper class and the white working class. After covering 1700 miles and 7 states this fall I felt better prepared to comment on Vance’s report.

As Vance summarizes: “A recent study finds that unique among all ethnic groups in the United States, the life expectancy of working-class white folks is going down. We eat Pillsbury cinnamon rolls for breakfast, Taco Bell for lunch, and McDonald’s for dinner” (page 148).

Here, some tell us, was 2016 Presidential candidate Donald Trump’s angry electorate and for the moment that description holds. Yet it appears that Trump’s victory is more symptom than cause. A visit to part of the vast American heartland helps gauge the strength of that analysis.

A drive along Interstate Highway 40 from Los Angeles to Memphis, TN convinced me that most Americans are invariably hard-working, helpful and good at their jobs. There is however evidence for some of the desperation Vance chronicled in 2016. He sounded a judicious warning to our political class that while “there is no government that can fix these problems for us” there is still something that might be done in an individual sense. Vance’s phrase was, “putting your thumb on the scale for people on the margins.” He doesn’t mean this in a blaringly cocky libertarian “up by the bootstraps” approach but in a steady insistence on the value of nurturing communities. Indeed he excels in speaking for those still-to-be found networks of extended families, committed church-going (especially churches committed to social action) and the importance of successful role models. The last reminds people that there is more than one side to the Hillbilly experience.

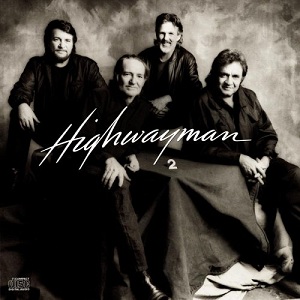

Singers who never forgot their rural roots.

Singers who never forgot their rural roots.Night in H-Town

Highway 40 cuts straight across Oklahoma which Vance sees as a “have” state along with Utah and Massachusetts. These regions, he claims, are “wiping the floor with places such as Rust Belt Ohio” where he mostly grew up. This might be an exaggeration if the somber depiction captured in the film, “Manchester by the Sea” (2016) set in Massachussetts, and similiar reports from an Anthony Bourdain episode on CNN are any indicator. Joblessness, runaway prescription drugs, meth and rural despair now seem as endemic in the rural Northeast as in the Vance tableau.

H------, Oklahoma might make a sample paradigm. The people at the information center in Western Oklahoma will sound a mild warning to the traveler just crossing the foggy baldness of the Texas Panhandle that, in way of motels, there is “not much beyond Oklahoma City.” H-Town is east of Oklahoma City at the intersection of I40 and U.S. 75 leading to Tulsa, the strong urban magnet in this part of “drive-through” country. Location, that strategic catch-all, makes possible a kind of economic buoyancy in H-Town but even here a social divide jumps out at you.

It strikes home in the discrepancy between the garish gambling casino sign that towers over Main Street with its host of fast-food outlets. This is in great contrast to the roller coaster back streets of town. Those swollen intersections where blacktop has been too long left to the heat and cold mark out a deserted thoroughfare for out-of-towners like us, seeking a bed for the night. It leaves an eerie feel to creep past houses that seem forlorn and dilapidated along the darkened back roads.

Contrasting Main Street H-Town with garish Main Street reminds one of John Kenneth Galbraith’s line in his 1957 expose, “The Affluent Society.” Galbraith commented on the “curious unevenness of [our] blessings.” The phrase has always stuck with me. Consider. At Shoney’s on Main Street boisterous Oklahomans (think of confident Curley from Rogers and Hammerstein’s glowing vision) eat and drink with an almost frenzied gusto. That almost Viking-like mead hall bravado in the shadow of the dominating casino sign evokes an image from the 1946 movie “It’s a Wonderful Life.” Only it is the tragic side of “Potterville,” George Bailey’s nightmare version of sedate middle-class Bedford Falls, a town doing well in the raucous post-World War Two buoyancy.

Back at Henryetta’s newly renovated motel another scene evolves. A harried working class mother of two is trying to coax a bargain out of the efficient immigrant owners while her grim-faced daughter strokes a pet dog inside her windbreaker. The pathos leaps out at you.

Vance’s dichotomies seem to come together here: hard-up working class whites seeking a place for the night while eager immigrants scan the ledger. All of this in counterpoint to the overflowing noisy fast-food joints up the street. Has gaudy Potterville finally triumphed? Even the Wal-Mart, a sure index to commercial success in most towns, manifests a weariness and lack of typical consumer zest that we saw evident in Gallup, New Mexico, for example. The valiantly friendly Wal-Mart clerks move slowly. They are older and slower if still friendly. Maybe November and impending winter is to blame but if America the Prosperous isn’t obvious at Wal-Mart what hope elsewhere?

Riveting Contrasts

Is this the dreaded “hollowing out” of rural America Vance touched upon? Is this today’s rural reality where hard-scrabble back streets exist cheek-by-jowl with the seemingly happy face of affluence roiling along Main Street? The quiet friendliness of the mother and daughter at the local Arby’s and the jovial hostess is a merciful reprieve. Their friendliness undercuts the somber picture somewhat, but overall H-Town makes a sobering scene to the late-night traveller. Naturalist Wendell Berry’s 1970’s paen The Unsettling of America comes to mind or more recently intimated in the television series “Breaking Bad.” Set in that very Gallup, New Mexico where Highway 40 speeds one along through rural beauty, “Breaking Bad” featured a struggling high school teacher turning into dedicated meth dealer. The overtones of the 1971 movie "The Last Picture Show” with its evocation of a dead-end Texas town are hard to miss.

Rural decline has been going on for some time if popular culture is any indication. The morning paper shows that Blake Shelton of television’s “The Voice” is a popular figure in H-Town. A native Oklahoman, Blake plans to rally the spirits of his and Vance’s white working class with his own version of the Farm Aid productions extant since the 1980s. These attempts at rural uplift were inaugurated at a time in 1985 when 100 crosses were placed across the street from the White House, starkly depicting the number of family farms going out of business each day. Here was a hollowing out proceeding apace in the vaunted economy of the Reagan years. How much can the Heartland take? “We got the down but we didn’t get the trickle” as one social activist poignantly put it.

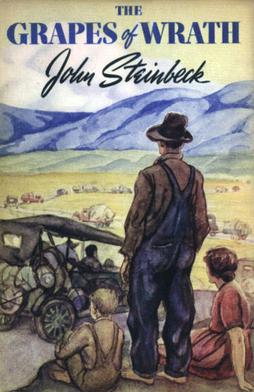

Farm crisis of the 1930s.

Farm crisis of the 1930s.

Boom and Bust?

Farm Aid itself is an apt reminder of how long the rural crisis has been around. Historians catalogue that one of the triggers of the Great Depression of the 1930s was the farm crisis of the 1920s. The phrase “Dust Bowl” conjures up a rural America devastated by collapsing farm prices after World War One – the uphill struggle to keep plodding along in “next year country.” Both radical historian Gabriel Kolko and centrist David Kennedy in Freedom From Fear reminded readers in the 1990s that the boom-bust cycle on the Great Plains of the 1880s was so intense that fully one third of new immigrants returned to central Europe especially. One full third. That shows how uncertain and precarious life on the land can be. Even this land where Jefferson’s vision of small landholders supporting a sturdy nation of yeoman farmers gave way to the vagaries of mass production, agribuisness, the banks, the foreclosures and railway baron speculations. That and the locusts, boll weevils, blight, rust, and the forcing of the soil which sets up the bleak back story to John Steinbeck’s 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath.

The question hovers: has it always been more difficult to make it on the great lone land, even amid the rural splendor of Vance’s Hillbilly Arcadia? Many of these blunt realities helped make quasi-folk heroes and pop culture avatars out of Jesse James, Butch Cassidy and Bonnie and Clyde because…they robbed railways and banks! This is why even Republican pundits argue that Donald Trumps’s 2016 electoral victory was a symptom and not a cause and perhaps operating on a short half-life. The era when Ronald Reagan could intone “government is the problem” is checked by “fixing the mess in Washington.” President Clinton’s “big government is dead” may seem premature. “Drain the swamp,” we hear, but, yes, use government powers to do it. Fix the problem, please. We’d like the trickle as well as the down.

As conservative commentators George Will and Charles Krauthammr regulalry insist: this is not true small-government conservatism. It is American pragmatism, perhaps, taking another turn.

David Kennedy’s history of the New Deal fittingly quotes philosopher William James: “The world is not a finished place, nor ever will be.”

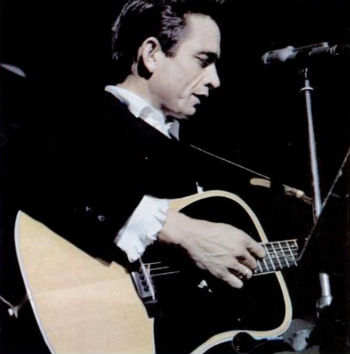

Johnny Cash

Johnny CashArkansas’s New Deal Throwbacks

East of H-Town further along Interstate 40 comes “the natural state” of Arkansas whose lush vegetation and rolling forested hills can seem a world removed from eastern Oklahoma, that landscape that registered harshly on Barbara Kinsolver’s heroine in The Bean Trees. The official travel guide for Arkansas mentions a town not too far off the beaten path. That would be up in the Delta area. Dyess, Arkansas is the home of singer Johnny Cash whose ballads such as “Five Feet High and Rising” and “Daddy Sang Bass” evoked overtones of yet another uphill struggle in hard-scrabble times:

I remember when I was a lad

Times were hard and things were bad,

But there’s a silver lining behind every cloud.

Just four people that’s all we were

Tryin’ to make a livin’ out of black-land dirt

But we’d get together in a family circle singin’ loud.

The Historical Dyess Colony is celebrated in the official visitor’s brochure with the explanation that it was “created in 1934 as part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal to aid in the nation’s economic recovery from the Great Depression. The federal agricultural resettlement community provided a fresh start for nearly 500 impoverished Arkansas farm families including the Cash family who relocated to Dyess in 1935.”

Today a rash of conservative historians have risen up explaining that World War Two, not FDR, ended the Depression. Be that as it may, the simple exigencies of getting a crop to market – grain or cotton – leads to a dependence on railways, financiers and transportation supply chains that leads to a degree of interference. This kind of “meddling” people as proud and feisty as those Vance chronicles don’t like. The dice does seem so often stacked against them. Vance’s own family moved from the rural glory of the Kentucky hills to the factory town of postwar Middletown, Ohio. There the Armco steel company made possible a lunch-bucket way of life in the 1950s that paid the bills and supported the family, with perhaps an occsional trip to Niagara Falls thrown in as a sweetener.

Vagaries of Globalization

In the fierce global competition of the 1980s Armco was saved by a merger with Kawasaki in Japan – a sign of those times. It was always that way, when produce headed back to Eastern factories for processing and packaging. But globalization considerably upped the hazards…and the middelmen. The world stage meant a global system tied even more to the vagaries of supply and demand, cheap overseas competition, and the standard litany of globalization’s discontents. It is a reality hopeful Americans in “next year country” seem to have a hard time admitting to each other: even America's system of regulated capitalism doesn’t always guarantee good times. Admitting that we are all in this together and that there is sometimes a role for government to step in and offer help – the Dyess Colony writ large – cuts across the grain of America’s fierce individualism.

In the renewed form of populism in vogue today it is often forgotten that American-style populism was originally a movement from the left of the political spectrum. It emerged in large degree from small-town farmers organizing politically against the perceived injustices of freight rates, gimlet-eyed bankers, credit agents, currency manipulators and “government men” back East. The Populist Party of the 1890s eventually controlled four Midwestern states and launched a respectable Presidential candidacy in 1892 that garnered 1.0 million votes to Grover Cleveland’s 5.5 million.

More than a century ago now this legacy of protest helped prepare for the reforming presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. In the 1890s the cry was “raise less corn and more Hell” and today it is “the good jobs are gone and let’s get them back.”

In their own separate ways both political parties in 2016 produced candidates calling for some kind of collective response to the hurting heartland’s crisis that Vance sees engulfing the white working class. Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump echoed Al Gore’s campaign themes of 2000.

“A Problem-Solving People”

In 1997 British historian Paul Johnson concluded that “the Americans are above all a problem-solving people…they will not give up.” No doubt there are answers but they may tax the creativity of the whole political spectrum rather than clinging to the blaring certitudes that “government is the problem” or “we need more government not less.” Vance offers evidence that over-much interference in the form of child services rending children from unhealthy homes can undermine one of the redeeming mainstays of his upbringing – the tough love and reassurances from his extended family. He meant his grandparents in particular, Mamaw and Papaw, whose catalytic presence curiously echoes that of Maya Angelou’s small-town Arkansas grandmother in “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.” Here is a blow for traditionalism of the kind conservatives can celebrate.

On the other hand the other savior in Vance’ life was the United States military in the form of the Marine Corps. “It was the Marine Corps that first gave me an opportunity to truly fail…and, then, when I did fail, gave me another chance anyway” (page 175). This seems like another victory for the right of the political spectrum, which in some ways it is. However, a closer look leads to a more equitable conclusion. A troupe of historians from William C. Berman to Jacob Vander Meulen to David C. Lewis have written over the decades about “military Keynesianism,” or “Roman imperial capitalism.” One place a majority of Americans seem prepared to spend a king’s ransom on without much objection is the United States military. Every since the formula of “emergency federalism” worked to help win World Wars One and Two, American politicians know they can get away with carving out a huge slice of the nation’s budget for military expenditures and all the special benefits applied. The only popualist backlash is slight indeed as, for example, when the armed forces underwrite sex change operations.

It could be argued that the military is the American people’s largest form of public expenditure of the kind Galbraith and others championed. Vance detailed that “contrary to conventional wisdom, the military is not a landing spot for low-income kids with no other option.” Both rich and poor are well-represented in one of the few virtual “we’ll look after you” public enterprises Americans will support. This development is not unopposed. Cold War necessities seemed to make a militarized state a necessity and President Eisenhower could see what was coming in his late warnings against the “military-industrial complex” in 1960.

Vance got his fresh start through the Marine Corps, just as the Cash family did at Dyess Plantation. Good for them both. Both agencies of government, in essence, offered a communitarian agenda. Both sides offering a hand up not hand out. The New York Times asserted that Vance’s testimony of rural brokenness and uncanny resilience speaks to both sides of the political spectrum. Thus, as unsettled as the situation appears in Vance’s lament and in the garish imitation Pottervilles created by the shifting economy, certain constants may still be traced. There is the lesson that in a healthy democracy hearing all sides of an argument is a key to moving forward. The answer lies not in a simplistic return to Andy Griffith’s Mayberry (still an enormously popular show in re-runs) or in a Huey Long-like “share the wealth” scheme of the kind Americans usually see through. Moving forward once again as a collective enterprise may entail an embrace of the communitarian spirit that animated some of the best instincts of the political culture in times past and which the popular culture often reflected, and still does. Vance’s tome, bleak as it often is, evokes the 1970s TV show “The Waltons.” But it still has that undercurrent of robust Americanism which Ma Joad articulated in the 1940 film version of “The Grapes of Wrath:” “We’re the people that live. Can’t nobody wipe us out. Can’t nobody lick us. We’ll go on forever. We’re the people.”

The political party that can tap into this artesian well of battered but still breathing spirit of Americanism may yet claim a steady hold on the future. After all, the world is not yet a finished place, a needed reassurance in our unsettled times.