Yes, God Will Forgive You

By Neil Earle

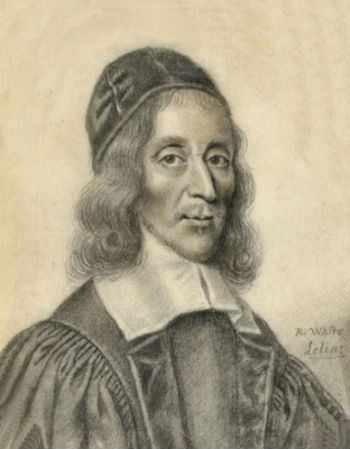

George Herbert

George HerbertThe very best words on forgiveness when up against crushing, debilitating feelings of sin and unworthiness are the Psalms. The Gospels tell of what Jesus said and did but the Psalms tell us how he FELT!

Yes, there’s nothing like the Psalms for wounded sinners. Believe me, I know as one myself. But sometimes other words speak to us almost as powerfully. At UCLA English class forty years after my early undergraduate work, I got to formally study once again the religious poetry of the talented Anglican Dean of St. Paul’s, John Donne (1571-1631), and the English country parson George Herbert (1593-1633).

Both wrote forcefully on divine assurance for sinners, the triumph of grace whereby the believer achieves certainty in the matter of personal salvation. Both Donne and Herbert did this by connecting “the sublime with the commonplace.”1

Forgiveness…and Acceptance

It is Herbert’s poem Love III, however, that I find revealing of an acute, intelligent reflection on the doctrine of grace – the fact that God will forgive us and, beyond that, accept us. This one poem has helped me and my congregations through the years see the exquisite intimacy of the God-child relationship and the sense of creatureliness and alienation we feel when we need forgiveness. Perhaps it can help you. At such times feelings are all-important for negative emotions can conspire to sever the bond between creature and Creator and plunge us into the Lower Hell of abandonment and hopelessness.

The great Reformer Martin Luther himself felt this many times and confessed: “As if indeed it is not enough that miserable sinners are crushed by every kind of calamity by the law of the Ten Commandments without having God add pain to pain by the Gospel’s threatening us with his righteousness and wrath.”

But Luther won through to full assurance. So can you and I. Herbert’s simple-seeming yet deeply spiritual meditation offer an antidote to the depression and unworthiness that Christians experience after sinful encounters. Here is my commentary – stripped of some of the class paper terminology.

Lord of the Banquet

Herbert was an English aristocrat, a respected leader at Oxford University, a dissenter from the politics and war of the day. In a compressed and thrilling metaphor of the Banquet analogy (one of Jesus’ favorites – see Revelation 3:20) he communicated his real-world country parson’s understanding of God’s forgiveness.

Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-ey’d Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning,

If I lack’d anything.

Here, in swift-moving style, is Herbert opening his exquisite fifteen line meditation with an analogy most Christians conscious of personal sin can well understand. The mix of long and short lines convey the sense of caution, of guilty hesitation: “Will God accept me? Have I really blown it this time?”

“Love” here is obviously Jesus Christ in poetic guise as the Gracious Host or Lord of the Banquet (Luke 14:16). The invited one is hesitant to approach his perfect Lord. But…but alert and “quick-eyed Love” spots this discomfort and guilt immediately. Love will accept no excuses. Love takes the initiative. She draws near “sweetly questioning,” an aspect here of the feminine principle as in Mother Love, as are the two “my dears” later in the poem, Scriptural echoes of Proverbs 9:1-5,

“Wisdom has built her house…she also has set her table (the dinner party theme again). She has sent out her servants, and she calls…‘Let all who are simple come to my house…Come, eat my food and drink the wine I have mixed.’”

Herbert knew his Bible well. According to one source it was the poet/parson’s practice to read two Psalms daily and to join in an ongoing communal group reading of the entire book of Psalms (George N. Wall, George Herbert: The Country Parson, The Temple).

Yet Herbert, as hard as he tried, was no stranger to “dusty sin.” Sin and guilt tell us “I’m unworthy to enter his presence let alone enjoy a divinely-prepared love feast.” The guest feels unworthy and must shy away from the Invitation. Yet each argument is met with a better, more elegant and gentle intelligent response – Grace in action!

In reply to the question whether the guest lacked anything, his Guilt is obvious:

A guest, I answered, worthy to be here:

Love said, You shall be he.

I the unkind, ungrateful? Ah, my dear,

I cannot look on thee.

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

“Who made the eyes but I?”

“Who made the eyes but I?” is a gentle rhyme yet powerful at this point. It begins to turn the corner for the distraught guest. It again confirms who the Host really is – our kind and compassionate Creator who, said the Psalmist, knows us better than ourselves (Psalm 103:8-14).

The implied term “Host” here is important. Some think Herbert, as an Anglican minister, is implying a double-edged reference to the Communion bread, or Host, as some churches call it. That may be so, an example of the elastic suggestiveness of religious poetry at its best.

Blessed Reassurance

A major point at this juncture, however, is that there seems to be no final answer to Love’s astonishingly gracious reply in the second stanza. No answer merely excuses. Yet the Host’s tone is unfailingly serene, gentle, courteous, reflecting Herbert’s Reformation sense of a strong assurance of God’s unfailing favor. Literary scholar Helen Gardner catches it perfectly: “The image…is an image of a soul working out its salvation in fear and trembling. The two poles between which it oscillates are faith in the mercy of God in Christ, and a sense of personal unworthiness that is very near to despair.”2

Stanza two is suffused with the great Christian doctrine of justification by faith so why do we need another stanza? Ah, this shows Herbert’s deep pastoral understanding of the reality of sin and the psychology of sinners – of his own struggles against sin. Just one answer may not convince convicted sinners. As an Anglican parson Herbert knew that even more assurance was needed. Thus his next four lines are vitally necessary to the argument. In answer to the question “who made those eyes” he has the guest protest:

Truth Lord, but I have marr’d them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.

And know you not, says Love, who bore the blame?

My dear, then I will serve.

Eyes marred with sin? Yes. Which Christian repenter has not felt that sting of conscience and the fear that, finally, this time, all is lost?

True Communion

Herbert’s two souls in communion in Love III is a much kinder, gentler reiteration of Luther’s much more graphic and forceful description of the sinner’s plight. Yet both are ultimately on the side of the repentant sinner. Herbert’s last two lines end the argument with his conscience and with the God who created it:

You must sit down, says Love, and taste my meat;

So I did sit and eat.

The final word picture depicts almost everything warm, kind and inviting to the wounded and the penitent soul – true Communion at last. Home again! Nothing could be more calculated to spell Assurance than sharing a meal with one’s Creator-Redeemer.

In the guise of a patient, loving Host, God invites communion with sinners. The banquet here referenced is in the Biblical mode of Jacob eating with Laban, the elders of Israel eating and drinking with the Lord God on Mt. Sinai, Jesus breaking bread at the Lord’s Supper and the gracious Host knocking at the door in Revelation 3. It has been well-said that in ancient Middle Eastern cultures, whom you ate with was more important than who slept with. The sharing of food here represents the triumph of grace hard-won after real and remorseful repentance.

Herbert’s message? Even dusty sinners can expect restitution at the hands of a God who has provided both the incentive and the mechanism for forgiveness of past wrongs. With such a Host sinners need have no fear. God will forgive us.

1. Joan Bennett, Five Metaphysical Poets (Cambridge: CUP, 1964), page 3.

2. Helen Gardner, John Donne: The Divine Poems (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952), page xxxi.