Why They Called It…The Miracle of Dunkirk

By Neil Earle

In our Newfoundland “readers” of the 1950s (published in Ontario), we had a poem “The Little Boats of Britain.” It read in part:

“The ships that sailed with Nelson and Drake, that broke the Armada’s pride;

And the little boats of Britain shall go sailing by their side.”

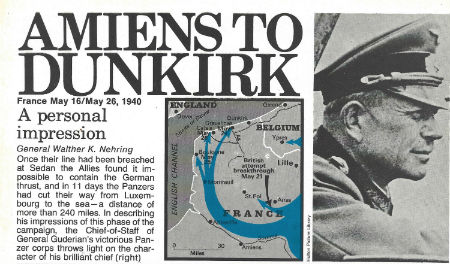

The reference of course was to the famous Dunkirk evacuation of May-June 1940 when 338,226 mostly British soldiers were rescued from death and shame by an all-out effort from the Royal Navy, the Air Force and most surely the 800 or so little boats. Even Christopher Nolan (pictured below left), architect of the latest “Dunkirk” movie opined how the effort is part of every Briton’s DNA. Pleasure craft, yachts, ferries, 18 foot fishing boats, paddlewheels and other civilian volunteer craft answered the call to cross the Channel and rescue the beloved Army.

And a Newfoundlander was there, flying above the skies of the trapped army fending off the mighty Luftwaffe. He gave his life as part of the RAF’s 125th Squadron formed and subsidized by Newfoundland’s Commission of Government in 1938 and 1939 to give the island a stake in the emerging jockeying for air supremacy. The air war over the French beaches, as Winston Churchill informed the Nation afterwards, was catalytic to the success below.

Christopher Nolan

Christopher NolanThe “Dunkirk Miracle” stunned and startled the world. The redemption of the army gave heart to the British and their dominions overseas to carry on the struggle against Nazi Germany. It also gave the silent ally in Washington more time to reflect and rearm. What some had called “the Phoney War” and the “Sitzkrieg” that had obtained from fall 1939 to summer 1940 ended in a flurry of storm troops and mechanized legions slicing through France and Belgium in an outflanking move that sent the small British Expeditionary Force falling back on the beaches where seemed little chance of their safe return to England. Dire times. The night of May 25, 1940 there was a partial blackout in St. Johns; so close were the connections at the time. Soon after the Royal Canadian Air Force sent five Digby aircraft to the field at Gander and elements of the Black Watch of Canada cemented a military intervention that would signal different times ahead for the island.

Dunkirk was just that central to all our lives.

The Little Boats

But it was the 800 or so little boats that captured the imagination of the world. The smaller craft could get in closer to the beaches where destroyers could not go.

Dunkirk created a popular surge of self-sacrifice that made the world marvel. Without the Dunkirk miracle Britain might well have succumbed to calls to make peace with Adolph Hitler. There would have been no Battle of Britain later that summer when barely 2000 Allied airmen handed the Nazis their first defeat and – just maybe – saved the world.

It took a long time to have an epic movie matching the epic events off the dunes because, as Christopher Nolan argued, there were no Americans involved and the technology for capturing land/air and sea sequences hadn’t arrived.

“Where are the Newfoundlanders?”

As Peter Neary mentions in his Newfoundland in the North Atlantic World, 1929-1949, the first Newfoundlanders to answer the call in World War Two were seafaring men. Some 198 Royal navy recruits freshly commissioned recruits sailed out of St. John’s for Halifax and on to England on 14 September, 1939 – only 11 days after Britain’s declaration and four days after Ottawa made the move. By 1942’s end almost 2900 had been enlisted under the white ensign. Ties to the Mother Country were still strong in those years and the navy had much cachet since everyone grew up hearing that Britannia still ruled the waves.

“Where are the Newfoundlanders,” snarled Winston Churchill in parliament soon after taking over the British Admiralty, “The best small boatmen in the world,” he added. One of these eager swabs was a future chronicler of Newfoundland and Labrador’s fighting sons, the author Herb Wells. Wells boarded the Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Newfoundland on May 14, 1940 along with 174 other young men just as the British army was contemplating its fighting retreat towards Dunkirk.

Dunkirk was costly. Richard Collier reported in The Sands of Dunkirk that of 848 Allied ships some 235 were lost. This included nine destroyers, 3 French destroyers, 19 damaged, 8 personnel ships sunk, and damaged. Of merchant sailors and civilians 125 were killed and 81 wounded.

Yet most felt they were part of something monumental if not metaphysical, the signal event of their lives. And how remarkable it was. In late May and early June the normally surly Channel was “smoother than a millpond,” infantryman Thomas Cooke told an ITV reporter. “Not a ripple was seen,” reported a Signalman Payne to Andrew Roberts. This allowed men to stand up to their shoulders in water and boats to operate within a few inches of freeboard, loaded to double, treble their safe carrying capacity. The calm sea was the miracle of Dunkirk (The Storm of War, p. 65).

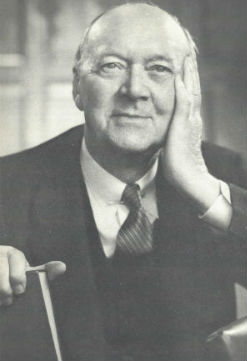

Newfoundland-born poet E.J. Pratt expressed something otherwordly about the events at Dunkirk.

Newfoundland-born poet E.J. Pratt expressed something otherwordly about the events at Dunkirk.“The Sea was their School”

The Dunkirk evacuation’s mystical side was not lost on a Newfoundlander at the University of Toronto, a professor of English born in Western Bay, NL. As E.J. Pratt he was destined to become Canada’s greatest narrative poet. Pratt was the son of a Methodist minister who would hold postings in Cupids (1885), Blackhead (1888), Brigus (1891) and Bay Roberts (1898). Pratt biographer David G. Pitt contends that the poet carried in his head indelible images of his boyhood spent in small Newfoundland outports – sympathetic depictions of an outdoor boyhood rooted in human and natural experiences that leave a mark.

The desperate miracle of Dunkirk, so dependent on the sea and the people who plied it permeates one of Pratt’s most stately and unappreciated poems, titled simply “Dunkirk” (1941). The surprise here is that though the British Tommies and their allies trapped at Dunkirk is Pratt’s main subject his poem emits overtones of a Newfoundland and Labrador upbringing.

“The sea was their school; the storm, their friend.”

Pratt had italicized this line in “Dunkirk” as well he might. As a Methodist pastor’s son he had accompanied his father on hardship visits to families where the breadwinner had been lost at sea. In “Dunkirk,” Pratt sketches with thumbnail efficiency the long, maritime history of the British, an expansion that had engaged Newfoundland and Labrador as early as 1497.

“They had swept the Main with Hawkins and Drake.

Morgan-mouthed vocabularians,

Lovers of the beef of language,

They had caved with curse and cutlass

Castilian grandees in the Caribbean.

They had signed up with Frobisher,

Had stifled cries in the cockpits of Trafalgar.”

Trafalgar, Frobisher, Hawkins and Drake were once names to conjure with in Newfoundland school “readers.” The phrase “lovers of the beef of language” could fit a puncheon tub full of Newfoundland politicians and public figures who need no naming here but who exhibited an unconsciously Shakespearian love of speech. Even place names comprise rhyming roundelays – “Hearts’ Content,” “Heart’s Desire” and “Heart’s Delight” or “Fogo-Twillingate-Moreton’s Harbour.” That gift for pungent robust speech lingers today in people such as Rex Murphy, Bill Rowe and the unforgettable Joey Smallwood.

Comedy and Spirituality

Pratt’s ever-present Newfoundland gift for comedy shows up in “Dunkirk.” Here is the poet celebrating the motley crews that traversed the English Channel to bring the army home:

“The Dean and his lordship, the Bishop, are here,

And your sloop, sir, is ready down at the pier.

And may I go with you?” Meadows said—

“No,” roared the Colonel, as he creaked out of bed,

Blasting out damns with a spot of saliva,

Yet the four of them boarded the Lady Godiva.

Who but a boy raised on the salty rhythms of workaday speech would duck the challenge of rhyming the almost improper noun “saliva?” Pratt’s latent Newfoundland wit shrewdly captures the community of seamen that saved the British in 1940:

Pratt’s keen ear for dialogue and dialect was matched by the religious sense of the miraculous near the end of the poem. In his final stanza the Methodist minister’s son pays full regard to the oft-remarked otherworldly features of the Dunkirk epic – the fog that sheltered most of the little boats and blinded the dive bombers, the treacherous Channel remaining as calm as a mill pond in place:

The Blessed fog—

Ever before this day the enemy,

Leagued with the quicksands and the breakers—

Now mercifully masking the periscope lenses,

Smearing the hair-lines of the bomb-sights…

And with it the calm on the Channel,

The power that drew the teeth from the storm,

The peace that passed understanding,

Soothing the surf, allaying the lop on the swell.

“Blessed fog” – surely an oxymoron for any sailor but effective in context. Pratt’s “peace that passed understanding” is of course, biblical, from Philippians 4:6-7 and it must have been a verse Pratt heard often as he heard his father’s sermons. Linked with the quite descriptor “Blessed” it conveys a sense of benediction both on the Dunkirk Miracle and on Pratt’s finale, underscoring that there is often more going on than meets the eye in human affairs and that not far from the center of world-shaping events.

Christopher Nolan’s movie is the hit of the summer and it was high time, perhaps, for an epic retelling. But for those of us who grew up in the shadow of these epic events our splendid little “readers” and Pratt’s heroic verse will carry the day.

(Neil Earle was raised in Conception Bay, Newfoundland, and teaches history at Grace Communion Seminary in Glendora, California.)