Viktor Frankl and the Cry for Meaning

By Neil Earle

Viktor Frankl

Viktor FranklIn 1997 I almost got to meet one of the late 20th century’s most respected authors and therapists. Unfortunately he was unable to be in Toronto because of his last fatal illness as a 92 year old man.

What a life Dr. Viktor Frankl (1905-1997) had. He was the founder of the “third Viennese school” of psychotherapy, behind the legendary Freud and Adler. At the core of Frankl’s belief was the conviction that human beings are characterized by a thirst for meaning, that even the most dismal circumstances can be endured if not conquered once a purpose can be found that makes some sense of suffering. Frankl’s hallmark book, Man’s Search for Meaning, sold nine million copies and was translated into twenty-three languages. It was written in 1946, after his experiences as an inmate in Auschwitz concentration camp, that living hell built by the Nazis. Frankl survived, stronger even when his belief system that there was meaning to life met the sternest test imaginable. Frankl’s philosophy was deceptively simple but profound in its implications, as can be gauged by the following excerpts:

- “A human being is a deciding being.”

- “Between stimulus and response there is space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

- “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

- “Everything can be taken from a man or woman but one thing: the last of human freedoms, to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

If there is more than a little of a mid-20th century “existential” tone to Frankl’s statements that is because he never shunned the label. Viktor Frankl was very aware of the leading currents of thought in his time. Born to a Jewish family in Vienna, Frankl earned a doctorate in medicine in 1930 but found himself drawn to psychology after earlier offering an exceptionally successful program to counsel students on the verge of suicidal depression in 1924. From 1933 to 1937 he treated more than 30,000 women tempted towards self-extinction at the “suicide pavilion” of Vienna’s General Hospital. When the Nazis took Austria in 1938, Frankl began his stints in various concentration camps. The war led to the death of his wife and entire family except his sister. This was the trial by fire of his deepest convictions, expressed in a memorable passage in his own words describing Planet Auschwitz:

“The guards kept shouting at us…hardly a word was spoken, the icy winds did not encourage talk. Hiding his mouth behind his upturned collar, the man marching next to me whispered suddenly: ‘If our wives could see us now!’ That brought thoughts of my own wife to mind. And as we stumbled on for miles, slipping on ice spots…we both knew: each of us was thinking of his wife.”

A Revelation

This brief reverie led prisoner Frankl to a moment of revelation: ”I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for a moment, in the contemplation of his beloved. In a position of utter desolation, when man cannot express himself in positive action, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way – an honorable way – in such a position man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfillment…Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love” (Man’s Search for Meaning, 1984 edition, pages 56-57).

Out of the depths – Frankl survived this prugatory.

Out of the depths – Frankl survived this prugatory.This insight gave resilient life and zest to Frankl’s cornerstone conviction: “The last of human freedoms [is] the ability to choose one’s attitude in a given set of circumstances.”

How fitting – and yet not really so strange – that Frankl’s life experiences, medical practice and horrific setbacks should lead him back to a shared teaching of the Bible writer St. Paul. Paul rhapsodized that love is the strongest and most redeeming force in the universe. “Love never fails,” St. Paul wrote to his Corinthian church, “If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but have not love, I am nothing…Love does not delight in evil but rejoices in the truth. It always protects, always hopes, always perseveres” (1 Corinthians 13:8, 2, 6-7).

Before Paul Song of Songs, had hymned the glory and steely strength of unwavering, sacrificial love: “Love is as strong as death, its jealously unyielding as the grave. It burns like blazing fire, like a mighty flame. Many waters cannot quench love; rivers cannot wash it away” (Song of Songs 8:6-7).

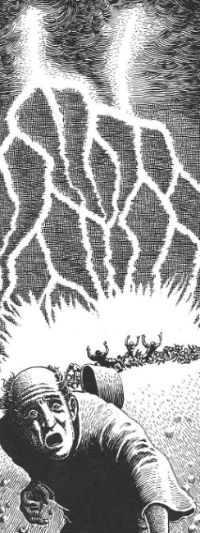

Poor Job's tragedies struck him in a single day but his faith in God's ultimate justice held fast. (Basil Wolverton artwork)

Poor Job's tragedies struck him in a single day but his faith in God's ultimate justice held fast. (Basil Wolverton artwork)A Matterhorn Book

It is also from the Old Testament that we find the book which has caught the attention of so many therapists and thinkers in our troubled times, Frankl included. It occupied the attention of both Carl Jung and renegade Jungian James Hillman. It resounds with Western literature’s most stabbing cry for meaning in the face of senseless tragedy. I am referring to the book of Job.

The book of Job has been called “the Matterhorn of the Old Testament” and “the book that speaks to tragedy more than any other.” Remember the story? Job, a rich sheik and cattleman, is a man who fears God so much that Yahweh is able to bet on his righteousness against “the Satan” (Job 1). God allows Satan to afflict Job with the loss of his ten children, his rich possessions, his prominence, his health. His three friends visit him and try to convince him that he must have done something to anger God (Job 2-4). “No,” Job insists, “I maintain my innocence. I am suffering unjustly.”

Job’s friends don’t know it but this is true. His three learned companions don’t know the back story. They continually charge Job with the dictates of the Retribution Doctrine, i.e. that bad things only happen to bad people (Job 22).

Finally God shows up in a whirlwind and exonerates Job (Job 42:7-9). God rewards him for his faith through all his trials, richly compensates him and reminds even his friend Job that human righteousness and good behavior count for nothing before God (Job 42:12-17). It is throughout the 38 chapters of Job’s sufferings that the question of meaning in suffering gets asked again and again and makes Job the patron saint of all who seem to be suffering needlessly. He seems suicidal at times but never takes it that far. Here are some samples:

“Oh that I might have my request, that God would grant what I hope for, that God would be willing to crush me, to let loose his hand and cut me off!” (Job 6:8-9).

“Does not man have hard service on earth?...I will complain in the bitterness of my soul…I despise my life; I would not live forever. Let me alone; my days have no meaning” (Job 7:1, 11, 16).

“Why does the Almighty not set times for judgment? Why must those who know him look in vain for such days?...If only I knew where to find him…I would state my case before him and fill my mouth with arguments. I would find out what he would answer me, and consider what he would say” (Job 24:1; 23:3-5).

Anger at God?

This verbal and philosophical battle between Job, his three friends, and a silent God continues through three cycles of accusations and answers. In Job 29 he laments the passing away of all he has. In Job 30:20-21 he almost signs off on a note of total despair, “I cry out to you, O God, but you do not answer…You turn on me ruthlessly; with the might of your hand you attack me”

A careful rereading of Job might reveal that he is as much concerned about personal honor – the ancient value of “face”” – as anything. Yet along the way he refuses to buckle to his friend’s shallow philosophy. Their clever arguments cannot shake him from demanding an explanation from God, some meaning to his suffering. “But I desire to speak to the Almighty and to argue my case with God” (Job 13:3). He asks for a revelation, some understanding of the meaning for all this: “Why do you hide your face and consider me your enemy” (verse 24). Job’s cry resounds with sufferers across all time. Yet his faith stands solid: “Though he slay me, yet will I hope in him” (verse 15).

Job is not a man who doubts God’s existence. This is a man angry and bewildered at what God has done to him. Like Job we are not privileged to see “behind the curtain.” God is betting on Job’s faith and patience winning through. We read in James 5:11 of the legendary Patience of Job. He needed it. When God finally answers him out of the whirlwind, he answers none of his questions. Instead he merely gives his servant a display of his powerful handiwork in creation (Job 38-41). This puts things in perspective a little bit but it never answers Job’s cry of “Why?” Thus, it has been rightly said that the book of Job raises questions that are only answered in the New Testament.

“Get wisdom”

The question of why the righteous and the innocent suffer haunts our stormy times, from Auschwitz to 9/11 and beyond. Wise men and experienced counselors such as Viktor Frankl give us some answers. Indeed, it is part of Biblical wisdom to seek out wise counselors (Ecclesiastes 12:9-12). The very educated apostle Paul wrote that he was indebted to both the Greeks and the barbarians (Romans 1:14). The words of well-known poets and philosophers were on his lips (Acts 17:28). But ultimately Paul knew that God gives us not an answer but a demonstration. The heart of Paul’s teaching was the innocent death of Jesus Christ on the cross and how that death was redemptive (1 Corinthians 2:2).

Of all the innocents the most innocent of all was the one called Jesus Christ who suffered a horrible and brutal death. But his suffering and death had a purpose. It was redemptive. In Christian teaching it was by his death that Jesus paid the sins of all who ever lived and by his suffering he set us an example of lessons hard-won only through suffering (Hebrews 2:14-18).

The God who did not spare Job but eventually restored him, watched his Son die upon the cross and in the despairing cry of Jesus many have glimpsed the clue to meaning in suffering: “My God, My God why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46). Jesus was pushed to the limit, but even in his agony and pain it was still “My God, my God.” One can not know why the trials of life come the way they do. One can fail temporarily to see any meaning in the predicament. But this makes faith all the more important. Viktor Frankl also wrote: “Just as a small fire is extinguished by the storm whereas a large fire is enhanced by it, likewise a weak faith is weakened by catastrophes whereas a strong faith is strengthened by them.”

For the Christian, God is still there. No matter what.

One lesson of Dr. Frankl’s life is that even in this limited and mundane realm wise and compassionate people often find rich and enduring slices of meaning. Christians have the privilege to know that one day all suffering is going to be redeemed and even rewarded. God himself is the Great Equalizer. That is a promise from the One who tells us: “He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away” (Revelation 21:4).

Thank God for such a living hope.