Persepolis: Lessons From Ancient Persia

By Neil Earle

Photos courtesy of Creative Commons

Photos courtesy of Creative CommonsProfessor Ernest Herzfeld from Celle in Hanover province was chosen to lead the excavations at Persepolis in 1931. Almost 400 miles from Teheran in the southern Iranian province of Fars towards the Persian Gulf lie the ancient ruins of this once mighty center of the Persian Empire.

As a young man Herzfeld (1879-1948) had assisted the great Walter Andrae at the ruins of Asshur in modern-day Iraq at a time when Western nations were poring over the monumental treasures of the Middle East.

After World War I Herzfeld was appointed the world’s first full professor of Near/Middle Eastern Archaeology. Considered one of the leading Persian specialists in the world, Herzfeld was a natural choice to head up the excavations sponsored by the well-known Oriental Institute Museum of Chicago. The uncovering of the ancient Persian center of Persepolis (thought buried for good until AD 1620) took eight years and was finished by Erich Schmidt. Together these two experts were the first to use aerial photography on a “dig” and the payoff was enormous.

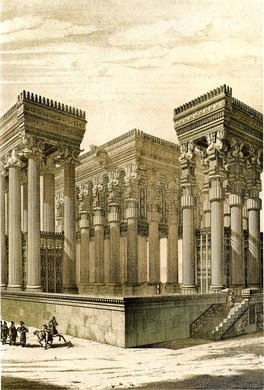

“The great audience hall”

We are still reaping the benefits. In the summer of 2016, the Oriental Institute of Chicago featured a major exhibit titled Persepolis: Images of an Empire which meant Herzfeld’s work is being appreciated as never before. Forced to leave Germany because of his Jewish background in the 1930s, Herzfeld was considered a “towering figure” in Near Eastern and Iranian studies. He eventually left his cache of 30,000 field notebooks, photographs and maps to the Smithsonian in Washington.

One thing he never got to finish was writing up a report on what he considered his archaeological crown jewel, showing forth the massive 1000 square meter “Apadana” or “audience hall” at Persepolis where kings such as Darius and Xerxes received tribute and obeisance from their many realms. Seventy two columns, each 24 meters high, composed the hypostyle of this main portico. Only 13 remained by the year 1900 but they attest to the grandeur of this once-mighty royal nerve center where emissaries from the far-flung corners of the empire can do obeisance. The open veranda feature on the three sides was unique in the ancient world creating an airy, spacious atmosphere that fit well with the more humane Persian approach to empire. The columns supporting the roof were 1.5 meters higher than the Temple of Diana at Ephesus and those ranked as one of the seven wonders of the world.

But why all this fascination with ancient cities and crumbling remains?

Because, there are many lessons for us today.

For one thing, anything that can foster a better understanding between Iran and the Western world is worth our attention. Ancient monuments and remains are part of the potentially rich and powerful legacy of today’s Middle Eastern nations – valuable assets handed down from the past that might still be activated for the all-important tourist and culture industries.

Secondly, our Western civilization stems from the triple apex of Iraq, Iran and Egypt. The world community would be greatly impoverished without these stupendous remains of the past, artifacts that cannot help but engender a respect for the peoples of these regions.

Thirdly, many Bible book such as Esther, Daniel, Chronicles, and Zechariah are rooted in the Persian period. This history – substantiated quite often by the science of archaeology – adds background, depth and realism to the Bible narrative.

The hypostyle, impressive even today.

The hypostyle, impressive even today.Kingdoms in Conflict

Nachfolge is a Christian-based magazine. It highlights the timeless message of the Bible for us today. The fascinating remains at Persepolis – like the Temple of Karnak in Egypt and reconstructed Babylon on the Euphrates – these man-made wonders point to profound reflections for Christians. Above all, pre-Christian memorials can remind us of stark differences between the kingdoms of this world and the heavenly-based Kingdom of God. After all, massive public buildings such as the Schoenbrunn, the Brandenburg Gate, or the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles ‐ impressive as they are – are architectural tributes to state power, to the colossal material forces sometimes brandished by the governments and rulers of this world.

In his Persepolis, die glauzene Haupstad des Pererreichs, Professor Heidemarie Koch explained how “overpowering” the visual impact of the city was from a distance. The Greek Acropolis in Athens aimed at the same effect. Even Solomon’s temple was designed to point men and women’s thoughts upwards, ideally to the grandeur of God and the rulers who had built it. Yet some human worshippers caught a glimpse of something more noble and transcendent than weighty buildings of stone. King David of ancient Israel, who prepared wealth and resources for the Jewish temple his son would build, showed himself at times keenly aware of the difference between the kingdoms of this world and the kingdom of God (1 Chronicles 29:10-15).

The kingdoms of this world run on power and might. The kingdom of God runs on meekness and humble service. David expresses these thoughts often, not in stone, but in writing the Psalms, his most lasting legacy. This is especially true of Psalm 15 where he shows the inner character of the ruler who would please God. He writes of ten watchwords that summarize the attitudes needed to please God. These words often make a stark contrast to the propaganda motivates behind many colossal remains of antiquity.

Let’s examine Psalm 15 and see for ourselves.

Who is worthy?

The psalm begins with a reference familiar to the ancient world – hills and high places where worshippers could bring their offerings before God. Persepolis was different. It was created in the shadow of mountains on the flat Iranian plateau country. But mountains such as Sinai and Zion were important to the ancients. Hence David correctly asks: “Lord, who may dwell in your sanctuary? Who may live on your holy hill?”

In the ancient world religion and politics were often joined together. The Pharaoh was worshipped as god, for example. Mesopotamians were a little more restrained but the kings of Assyria and Babylon were never bashful to claim divine honors. Darius I who began building Persepolis around 518-516 BC claimed he was doing all at the command of the chief Persian god, Ahura-mazda. This is on an inscription Herzfeld uncovered: ‘I am Darius, great king, king of kings, king of lands, son of Hystaspes…who constructed this palace,.”

Exactly the opposite spirit is conveyed in David’s opening line. The tone is humble and questioning even probing in its meekness – “Who may live on your holy hill?” Here is a major divergence between the kingdoms of this world and the kingdom of God. “Blessed are the meek,” taught Jesus, “for they shall inherit the earth.”

Though the Persian kings were considerably more humane than those who had gone before them, it was this Darius who was known to history as the invader and would-be conqueror of Greece. The Greeks had helped the Ionians on the coast of what is now Turkey (Asia Minor) in their rebellion against Persia. The rebels were put down mercilessly but Darius and his son Xerxes I both sought to crush the Greeks and add them to their empire (Daniel 11:2).

Meekness did not often characterize power politics back then. We don’t see much of it today either. Verse 2 of Palm 15 continues the contrast, praising the human worshipper who is “blameless” which means someone who is whole, sound – a term which is allied to “right” implying right dealing between men and God. In a word, justice. This is a word which governments ancient and modern often talk about but find it hard to practice. But some such as David and Cyrus of Persia caught at least a glimpse of it (2 Samuel 23:3; Isaiah 41:2).

The True Worshipper

Verse 3 of Psalm 15 esteems the worshipper who “has no slander on his tongue, who does his neighbor no wrong and casts no slur on his fellowman.” Here are valuable keys to the ultimate smooth running of any society or empire. Heathen kings and emperors liked to pretend that all justice and right dealing flowed from them but the hymn writers of Israel knew differently. In ancient Israel the theory of government was that even the king is subject to the laws of God. At their best some ancient monarchs practiced this principle as well but it was a principle more violated than not—again, as we see about us today.

Israel’s kings could bend the law to suit their own whims. Notice King Ahab defrauding his neighbor Naboth and the rebuke from the prophet Elijah (1 Kings 21). Few Persian, Egyptian or Chinese peasants thought there was anyone higher than kingly rule, but not so in Israel.

Another facet of godly character found in Psalm 15 is the praise ascribed to some who is not morally neutral but “despises a vile man” (v. 4). Here is another important principle of true justice. The corrupt and evil schemers must be weeded from the king’s presence else their advice will be hurtful indeed. The book of Esther is so vivid on this matter. It shows how Persian king Xerxes (Ahasuerus) – who finished the work at Persepolis – snapped into action when he heard about the plot his counselor Haman was hatching against the Jews. Haman was hung on his own gallows – rough justice but such were the prerogatives and power belonging to a king (Esther 7). Life and death were in the power of the king so how inspiring when he was true to his own words, a man of justice and fair play.

Psalm 15:5 highlights generosity vs bribery. Here was a virtue that ancient rulers employed to build up their reputation. We are reminded of King Ahasuerus’ words to Queen Esther, ”Name what you want and you can have it” (Esther 5:3). Extravagance was indeed a kingly virtue in the days of Darius and his successors. The king is encouraged not to “accept a bribe against the innocent.” Our Western democracies know all about this tendency today in the form of “lobbyists” and interest groups. There are few greater curses.

Promises that Last

“He who does these things will never be shaken.”

This strong conclusion ends with a promise. It sums up the hope and underlying moral strength behind Psalm 15. The powerful prescription for true service to God and man acts as a subtle check and a reminder to the ancient monarchs and worshippers just as they speak to us today. Indeed, the Psalms’ ten-fold call to moral and behavioral perfection can seem intimidating. But the New Testament shows how God can implant these qualities within us by making his very heart and nature available to us through the Holy Spirit (Romans 5:5).

Thus Psalm 15’s ten watchwords still broadcast forth to the world in a vehicle that has outlasted stone perfection – the inspired word of God. Ancient stone masterpieces such as Persepolis pointed to the power and grandeur of human rulers. Psalm 15 is the moral prescription for a new kingdom, the kingdom of God.

That kingdom is largely invisible. Instead of massive stone edifices God’s kingdom is represented by very human and fallible congregations that make up the Christian churches. Instead of towering rulers depicted on massive thrones to intimidate the gift-givers there is the life of the humble carpenter, Jesus of Nazareth who knew that true worship is a matter of the heart not outward pomp and grandeur.

The Persians contributed much to world history. They moved civilization forward in their day. But one does not need a temporary tabernacle or a mighty stone complex to catch a glimpse of divinity. The massive constructions unearthed in Persepolis were designed to evoke fear and dread in the defeated nations who anxiously approached the Great King. Massive stone bulls, lions and sphinxes lined the route on which nations left their tribute. One can imagine their representatives shuffling in slightly bowed over and shuffling out again.

But “the sacrifices of God are a broken spirit, a broken and contrite heart.” The Psalmist knew this (Psalm 51:17). The faded glory of Persepolis reminds us once again: earthly kingdoms rise and wane but the Kingdom founded on the attitudes behind Psalm 15 will stand forever.