Just Peacemaking: A ‘Possible Dream’

By Neil Earle

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s powerful speech to the U.S. Congress this March 3 attracted world attention. Many felt it a historic moment. Other feared it left the prospect of a Middle East conflagration much more likely.

In The Los Angeles Times of March 8, Israeli novelist Amos Oz, a Netanyahu critic, called for a peaceful resolution based on “separation and compromise” with the Palestinians while keeping a strong posture towards Iran. He feels the chances to solve entrenched conflicts in the whole Middle East are better now than ever. As he says, “the major regional players – Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, others in the region (the Palestinians) – face a destructive threat that is far more ominous than Israel.”

That threat is ISIS and the vision of a nuclear Iran that Prime Minister Netanyahu conjured up so forcefully. Oz is no wooly idealist. He urges a “dynamic peace effort with our Palestinian neighbors under the wing of the Arab Peace Initiative” as a way to defuse enduring tensions. To those who think it impossible he remembers: “My days in uniform in the Six Day War (1967) gave way to the Egyptian and Jordanian visas in my passport.”

True. Few would have expected Egypt, Jordan and Israel to have kept the peace since 1979. This was the result of President Sadat of Egypt’s bold peace initiative in 1977 and Israel’s steady peace diplomacy with Jordan.

The Christian Challenge

But what about Christians? Have we no voice in this? “Is there no balm in Gilead?” Must we simply pray for the Kingdom to come quickly? Well, the latter is never a bad option. But there are other paths Christians can help with before the nuclear genie finally gets out of the bottle.

Peace in this region may be a dream, but it could be a possible dream.

After all, as Oz says, things never change faster than in the turbulent Middle East.

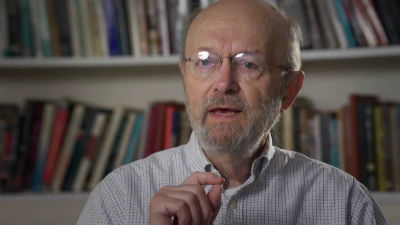

Let’s look off camera for a moment. Though they rarely make the “top of the news” well-organized Christian groups have been around for some time, advocating for peace and working for conflict resolution where possible. A prime leader was my late Professor of Christian Ethics, Dr. Glen Stassen (pictured, above left). Beginning in 1993 and again in a 2008 text, Professor Stassen outlined biblically-based principles of practical peacemaking buttressed by case histories from political science and recent history. His revised text is titled Just Peacemaking: the new paradigm for the ethics of peace and war. Glen had led a five-year project featuring twenty-three ethicists and international problem-solving specialists.

Describing themselves as neither idealists nor optimists but as problem-solvers, Stassen’s group worked on applying principles from Jesus’ teaching to modern-day conflicts.

Not Pie In the Sky

“Jesus was no Platonic idealist,” Stassen wrote further in the spring, 2009 issue of Fuller’s Theology: News and Notes. “He was a Jewish realist…[w]hen Jesus taught leaders in Jerusalem that they needed to practice peacemaking or the temple would be destroyed, he was talking realistically about a real threat and the practical ways to avoid the destruction of the Temple and Jerusalem – which happened.” This is true. Jesus was astute enough to see his Jewish folk headed for a first century holocaust, and said so (Luke 23:28: Matthew 24:1-4).

Stassen laments that many churches “have no Christian guidance when debates about peace and war arise.” Hence, parishioners “are undefended against ideologies that blow back and forth through our nations and our churches.” The goal is to teach broadly enough so that individual Christians “can decide prayerfully, which ethic seems right to them.”

Even Stassen’s critics admit his approach is refreshing. In his 2008 text Stassen and his colleagues presented ten practices to guide individuals and nations into the realm of practical peacemaking. We’ve boiled them down to seven “just peacemaking” principles which have the possibility to move Christian problem solvers and peace activists beyond the traditional “just war or pacifism” dichotomy.

Points to Ponder

1. First, practice nonviolent direct action. This is drawn from the famous “turn the other cheek” teaching in Matthew 5:38-42. The point here is not Christian masochism – allowing oneself to be smashed in the face for no purpose. Rather Jesus teaches to act in such a way that a well-thought-out, peaceful and determined response might oblige your opponent to reconsider his or her actions. Thus Jesus is seen as reacting non-violently to the High Priest’s false and deadly charges (Luke 22: 66-71) but he did react! He quietly but calmly asserted his rights before a kangaroo court. Our generation saw this method employed to great effect, says Stassen, by the non-violent civil rights protestors of the American South in the 1960s. The 50th anniversary of the Selma marches the same week as the Netanyahu and Oz public discussion made that point, if indirectly.

On the other hand Jesus also advised to not pick unnecessary quarrels with legally constituted authority (Matthew 5:25-26). Paul reinforces this strongly in Romans 13. Nevertheless, candlelight vigils, prayer walks, strikes, boycotts, marches, single-citizen protests, public media releases and disclosures, impendent monitorship, safe spaces (such as homes for battered women) – these tactics now make up the stuff of our nightly news. Ironically in this context it was civil disobedience (whereby protesters are ready to risk jail for their beliefs) which so worried the Iranian government in 2009 and was also a root cause of the fall of the former Shah of Iran in 1979.

As advocates Cortwritght and Thistlethwaite note, Twitter and Facebook have made it easier for non-violent activists to gather, organize and sustain a committee organized against injustice. These trends have proven powerful already.

2. Next: create independent initiatives for peace. This is taking actions to decrease the other side’s distrust or threat perception. Matthew 5:25 urges, “agree with your adversary quickly.” Stassen argues that President George H.W. Bush (1989-93) and Mikhail Gorbachev applied this in disposing of 50% of their respective nation’s nuclear weapons. Fuller student Kent David Sensenig sees Abraham taking an independent initiative with his nephew Lot when both men’s herdsmen were quarreling over pasturage. “Abraham willingly conceded to his younger nephew, Lot, the first choice of land, in order to keep peace in his family” (Genesis 13:2-12).

As we know, conflict was averted.

3. The timely application of cooperative conflict resolution. President Jimmy Carter helped achieve lasting peace in the 1979 Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel with just this tactic. Even President Sadat’s independent initiative to speak in the Israeli Knesset in 1977 needed a follow-up. The results have been 36 years of peace between once mortal enemies Egypt and Israel. For more see www.matthew5project.org.

4. An open acknowledgement of responsibility for conflict and injustice and (if possible) some form of sincere repentance and forgiveness (Matthew 7:15). This includes patient spade-work to develop creative solutions. Reconciliation leaders such as Ireland’s Evelyn O’Callaghan Burkhard sees this principle at work in the largely successful Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. Stassen colleagues Geyer and Shriver agree: “The moral authority of a [Archbishop Desmond] Tutu and a Nelson Mandela offer a powerful example of how political leaders can help their countries to transcend the burdens of their history.”

It isn’t easy. As a German statesman confessed to his nation’s legislature regarding World War Two atrocities “There can be no reconciliation without memory.” It took three U.S. presidents to engineer a final restitution and apology to 60,000 Japanese-Americans survivors of the internment in 1942. As President George W. Bush said, “in offering a sincere apology your fellow Americans have…renewed their traditional commitments to the ideals of freedom, equality and justice.” This resolution uplifted both sides.

To be continued.