NOT the Beatles – Pastor Neil accompanies friends in a 1972 English songfest.

NOT the Beatles – Pastor Neil accompanies friends in a 1972 English songfest.By Neil Earle

On Sunday night, February 9, 1964 73,000,000 Americans and millions of Canadians were glued to their television sets. Live from New York came four long-haired young lads from Liverpool, England to invade North America through the Ed Sullivan Show on CBS.

This event has been heartily celebrated on the major networks these past days – perhaps a little too heartily for Christian folk who have never been entirely comfortable with the offerings of the popular culture. This is in spite of surveys that show evangelical Christians in particular have almost exactly the same viewing habits as their neighbors.

Screenwriter Craig Detweiler at BIOLA (Bible College of Los Angeles) leads a growing chorus of other media professionals who work in or close to the entertainment industry. They have been urging Christians to stop grousing and try to understand the trends. They know that Jesus said to be aware of the “signs of the times.” The distinctive rock style of many of our new hymns these past thirty years show that the culture isn’t going to go away. The point is not to compromise with the culture – the New Testament is clear on that – the point is to not become irrelevant to that culture. Perhaps in better understanding what drives the mass audience we can be better prepared to help them.

You can be sure the fast food restaurants and other commercial entities exploit that principle.

So what happened the night of February 9, 1964? A new phrase entered the lexicon and rock and roll which was slacking off somewhat after Elvis joined the army enjoyed a new surge of life. “Beatlemania” seemed at the time as much a cure as a disease. The explosion of passion greeting four young musicians from Liverpool seemed to meet a real heart need for many North American youth. The timing of the Beatles success as displayed on Ed Sullivan’s family-rated variety show fifty years ago has intrigued historians. February 9, 1964, they tell us, was barely ten weeks after a far more ominous event – the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22, 1963.

NOT the Beatles – Pastor Neil accompanies friends in a 1972 English songfest.

NOT the Beatles – Pastor Neil accompanies friends in a 1972 English songfest.Here, claim musical and cultural critics such as Jonathan Gould, was the effective cause of that pop culture explosion called Beatlemania – at least in America. Child psychologist Martha Wolfenstein even drafted a book Children and the Death of a President (1965). The author claimed that John F. Kennedy fulfilled the role of a father figure for most of the youth disturbed by the events in Dallas just over two months before. At that time half the U.S. population was under 30, writes William Manchester. The Associated Press declared 1964 “The Year of the Kid.”

Kennedy’s death provided what Wolfenstein called “mourning at a distance.” Even the new First Lady said: “We feel as if the heart has been cut out of us.” As Gould summarized, Kennedy had been “a role model…whose sudden violent death had the power to force a confrontation not only with the loss of a parent but also, on a level that could not be acknowledged directly, with one’s own mortality as well” (Can’t Buy Me Love, page 218). Budding political journalist Jeff Greenfield concurred: “If he wasn’t safe, no one was.”

But, as Gould and others assert, when the Beatles launched into their falsetto “ooohs” and hairy head-shaking that night at Sullivan’s stronghold, it was time for the mourning to end and the party to begin. Beatlemania had arrived. It had been skillfully prepared by the release in England of their latest album “Meet the Beatles.” This LP featured the song that was intended to be their more moderate calling card in America – “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Implications of comfort and reassurance flowed from the lyrics. The Lennon-McCartney tactic of following a quiet, introspective moment (“And when I touch you I feel happy inside…”) before building to an over-the-top crescendo had the power to shake the rational outer defenses of the ego. It potentially swept the already engrossed into the higher emotional registers with “It’s such a feeling that my love, I can’t hide, I can’t hide, I can’t HIDE!”

In 1964, if you were a teenager with money to spend, Beatle music seemed fresh and inventive. There may have even been a subliminal effect at work in the fact that the Beatles had been raised musically on American rhythm and blues and the Elvis Presley explosion of the 1950s. Retired pastor John Adams remembers hoofing it across St. John’s from Memorial University to watch “Hard Day’s Night” downtown. “The Beatles clearly idolized our pop culture and sang it back at us doing us one better”--a driving, melodic back beat and captivating harmonics delivered by what even acerbic British journalists had called “four pleasant young men.” Christians should note that in 2010 the Vatican of Pope Benedict praised the early Beatles music for its optimistic lyrics and lively melodies, forgiving John Lennon for his misunderstood mid-Sixties outburst “we’re more popular than Jesus now.”

There was, of course, the untold story. John, Paul, George and Ringo projecting the image of fun-loving totally liberated mop-heads seemed to offer a new hope to a youthful generation under the shadow of the mushroom cloud and the Kennedy tragedy. These working class troubadours were already experienced men of the world. They had been raised beneath “the blue suburban skies” of gritty Liverpool. England in the 1950s – their cultural incubator – was not yet fully recovered from the austerities of World War Two. The Beatles had honed their musical skills in the seedy nightclubs of Hamburg, Germany. The exhaustion of all-night gigs and barely manageable accommodations found later expression in “I’m Down,” “Hard Days Night” and “A Day in the Life.”

Discerning eyes could see even back in 1964-65 that songs such as “I’m a Loser” and “Nowhere Man” made strained counterpoints to the exuberance of “She Loves You” and “From me To You.”

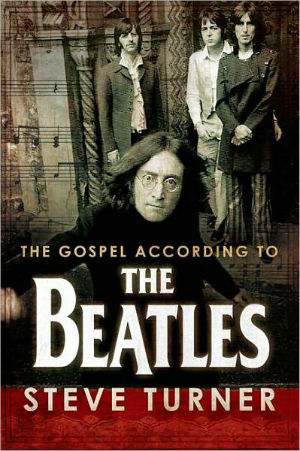

Steve Turner, a Christian writer, helped set the Beatle music and their lives in a religious context.

Steve Turner, a Christian writer, helped set the Beatle music and their lives in a religious context.We all know what happened next. Even the upbeat early Beatles music quickly spanned the gamut – from “I Want To Hold Your Hand” to “Help!” Later on the four musicians tried to assuage the emptiness they felt and sang about in a very public quest through the drug culture and Eastern mysticism. It’s a route many are still travelling today.

The Beatles, said friend and fan Steve Turner, a Christian writer, had the finances and the fame to explore their inclinations in a way few people can. They were mega-celebrities before the word became a fixture. But the dream-world of Beatlemania could never totally last, as dreams never do. Six years after their Ed Sullivan debut the band broke up and ten years after that their leader was tragically assassinated.

In some ways, as London columnist Bernard Levin wrote, the Beatles were highly visible victims of their own success. Screaming crowds drowned out their own voices on stage. After about 1966 they confined themselves to studio recordings. John Lennon was deathly afraid of the threats coming from outraged religionists after his “more popular than Jesus” comment. Their insightful sound engineer, George Martin, saw their slow unraveling across the Sixties as a product of truly talented composers yearning to explore their own separate styles. George Harrison delved into Eastern mysticism with “My Sweet Lord.” John was more political and more preoccupied with his girlfriend Yoko Ono and Paul’s predilection for sentimental ballads was irritating his peers.

Still, their moment was unusual. Lynda O’Grady, a retired elementary teacher, remembers it well. “It was all so different. Young girls saw them as cute and since there were four of them you had four to look at. They seemed to know it was their time, their hair styles and all that.” True. Their brash confidence was also refreshing. When asked at a press conference how they found New York, they replied, “We went to Greenland and turned left.” John told a Royal Charity audience they didn’t have to applaud simply “shake their jewelry.” Cheeky.

Still, the impact was vast. My 78 year-old grand-mother said, “I like their English accents.” So many of my college sing-alongs I led in the 1960s ended up singing “When I’m Sixty-Four” and the crowd-pleasing “All My Loving.” Everyone knew the words! My wife, Susan, inadvertently picked a Beatle song for our wedding day – “Here, There and Everywhere.” They definitely had the musical chops. Tim Welch, a sound engineer from Memphis, Tennessee, heard them in later years on television and emoted, “Those guys could really sing.” There is even a record that sets the Beatle tunes in a Baroque and classical musical style – and it works!

That they were a permanent phenomenon of modern music is evidenced by Paul McCartney’s sellout tours around the globe. He was asked to perform at a memorial concert in New York after the events of September 11, 2011. He closed out the 2012 London Olympics with “Hey, Jude.” The worldwide audience of youthful athletes seemed to know the words – all of them. On June 30, 2006 Cirque Du Soleil launched a Las Vegas tribute to the band. It was eloquently but simply titled, “Love.” The Beatles, for all their many flaws as human beings, inserted “Love” into their songs as much as any artists before and since. “Love Me Do,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “P/S. I Love You,’ “All You Need Is Love.” The pop circus extravaganza that made up their Sergeant Pepper album signs off with “Love is all you need.” Perhaps this gets close to the reason they have survived, as the Vatican may have intuited.

“In the 1960s,” opines pop culture professor Paul Rutherford, “the world overdosed on optimism.” We certainly live in different times today. Maybe here is a key to the nostalgic mood some people get when the early Beatle music massages our airwaves. Musicologist Casey Pitowsky of Cerritos College, California opines that “the real Beatle message was hope.” Christians know the source of that real hope. It’s a hope that doesn’t let you down. But a generation reeling from assassination and the vivid threat of nuclear terror would imbibe hope from whichever source could make it appealing in the stylistic forms of the day – guitars and drums. This is probably why, to vastly generalize, the world needed the Beatles with their optimistic backbeat.

The lyrics portrayed that as well. Consider “Hello Goodbye,” the song that pleads most insistently that

“Life is very short and there’s no time/ for fussing and fighting my friends.”

The call is still there, embedded for many for all time in the music: “Come together, right now.” Even Christians might concede – that’s not a bad message even five decades later.