By Neil Earle

“At this critical time evident madness is being shouted in our streets, but why do we lack the will to act in the face of this madness?”

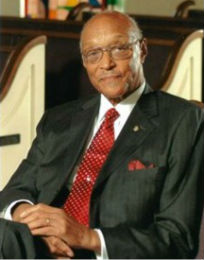

The speaker was former Dean of Tuskegee Chapel and former Senior Pastor at the Metropolitan Church in Detroit in the turbulent 1960s – Dr. James Earl Massey (pictured, right), close friend of Martin Luther King, Jr. and guest lecturer at Fuller Seminary’s second annual Black History Event.

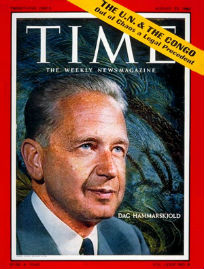

The “madmen in the streets” was a reference from one of Dr. Massey’s spiritual mentors, Dag Hammarskjold (pictured, below left), distinguished Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1953 to 1961 and author of “Markings” which Dr. Massey considered a “mystical” work. Hammarskjold defied pressure from both the superpowers in his term at the UN and which reflected much to his credit, Dr. Massey reminded the audience, as even President Kennedy had to admit to the man’s greatness after the Secretary’s untimely death. “Why are madmen allowed to cry in the streets?” asked Hammarskjold when facing the grim dilemmas of his time.

With more than a little swipe at the American media, Dr. Massey addressed four reasons why it takes a strong-willed person very much at home in their own shoes to resist the madness noised abroad today.

First, people don’t recognize the public misinformation as the madness it is. “We Christians need to see the Light of the Word of God shining on our times as Paul did when he talked of redeeming the times,” said Dr. Massey. “We must understand the problems, be informed and then inform others.”

Second, many lack the courage to risk resisting the madness. Thinking of the Civil Rights movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s, Dr. Massey continued: “We need that power of head and heart to accomplish a noble task – knowledge to address the mad theories being advanced and courage to oppose them with action.”

Third, there is so much misinformation and unbalanced theology. “People refuse to see that we are one subspecies of a diverse human family from one blood or ancestor as it says in Acts 17.” People who just wait for the kingdom undermine the use of kingdom principles to act upon the times here and now. Though Dr. Massey did not cite it directly he himself was well aware of Martin Luther King’s response to charges that he was stirring up social tensions. “We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive,” Dr. King had answered his critics.

A fourth stifling of the will to resist madness is a misunderstanding of what biblical agape love is. “This agape love is outgoing active concern to seek the good of others…we are not a true democracy, still an experiment…The madness of segregation continued until informed courageous church people insisted on Micah’s call to walk justly and love justice calling us to correct gross injustice.”

“The Third American revolution is now on,” continued Dr. Massey. “We in America have not known true unity since 1861. In every election the North and South are warring again. The Third Revolution is full equality, equitable sharing, concern for the common good, peace.”

His charge to the students and listeners resounded with prophetic force:

“Mad ideas are televised every day, we hear it every day.”

“Even schools are so partisan that mad ideas are not being challenged.”

“Don’t allow the nation to become a playground for destructive meanness.”

Dr. Massey vividly described Abraham Lincoln’s sleepless night before signing the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. “Lincoln did not see blacks as equal but he did see them as human.” The 16th President said as he signed the document, “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper.”

Dr. Massey affirmed his belief that through his many meetings with Frederick Douglass, the black abolitionist writer and lecturer of the mid-nineteenth century, Lincoln did come to see blacks as equals.

Massey then drew a parallel between Lincoln’s times, the 1960s and ours. Seven states had seceded when Lincoln was sworn in. In his time Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. galvanized thousands in spite of dogs, fire hoses and billy clubs and much bloodshed. “So today the will and wisdom to confront madness must be ours if we are to overcome evil with good.”

In answer to questions from the audience about how the churches can help confront the paralyzing fear that grips the country, Dr. Massey was not slow to respond. “Enlighten the people. Help them to see we’re all one. Inform ourselves first. Information comes first and then a depth of feeling in the soul comes naturally. That’s the way forward.”

From the warm applause that followed his remarks James Earl Massey had touched on some of the most salient lessons for a life well-lived in the struggle against racism and for removing the roadblocks to true democracy. One had the feeling he could cite out of his head texts and references for all the positions he asserted. Just to raise the name Dag Hammarskjold showed how long and deeply the pastor had thought about these issues. His call to act was not based on airy philosophizing. “Some thought slavery and segregation would never end but it did. The churches must raise mature disciples not just count members. And then we shall overcome evil with good.”