Slavery was endemic in the ancient world – and in the Bible!

Slavery was endemic in the ancient world – and in the Bible!By Neil Earle

Slavery was endemic in the ancient world – and in the Bible!

Slavery was endemic in the ancient world – and in the Bible!Derek Leman is a Messianic Jewish writer. His recent blog raised the intriguing and provocative question about the Old Testament Torah (books from Genesis to Deuteronomy) and the Biblical institution of slavery.

Intriguing because the way we Christians read Scripture – especially the Old Testament – is tied up in this kind of question.

Consider the bigger issue involved here. One of them concerns the whole subject of the Levitical system instituted at Mount Sinai. Was it God’s supreme moral statement of all time, giving Israel a constitution that must never be abrogated? Or, are we, as Leman put it, supposed to read Torah “as a conversation that evolves over time towards God’s ideal way in the world to come?” To put it another way, how can we avoid the apparent tension between what the New Testament writer Paul recommended as the “ministry of life” over against the Old Testament-based “ministry of condemnation” (2 Corinthians 3:7-11).

In the years before and after the great American Civil War (1861-1865) Christian ministers wrote on both sides of this issue with particular regard to slavery. Often with great heat and vehemence.

The arguments in favor of Torah-approved slavery actually appear quite convincing at first blush.

Slavery was practiced by Abraham and the Patriarchs. Abraham, father of the faithful, bought slaves and willed them to his descendants (Genesis 12:5; 26:13). Joseph made the Egyptians the servants of Pharoah (Genesis 47:15-25 – (“ebed” = servant = same word for “slave”).

Owning slaves and even bequeathing them to your children was permitted in Torah (Leviticus 25:44-46). Especially of slaves captured in war (Deuteronomy 21: 10-14).

In cases of extreme poverty, family misfortune or unpaid debts the law had an official ceremony whereby people could be voluntarily placed under servitude (Exodus 21:1-11).

And it is perhaps in that word “servitude” that some of the undermining of the pro-slavery arguments began to focus. Along with the taking of an indebted worker to the door of the tabernacle and boring his hole with an awl to signify servitude there came a host of more humane dictates clearly pointing towards “the ministry that brings righteousness” (2 Corinthians 3:9).

This voluntary Hebrew servant was normally to be set free in the seventh year, the year of release. “The boring through the ear” was only called upon if the servant was willing to continue under his master. Torah repeatedly admonished slave-owners to be charitable and generous: “Beware lest there be a wicked thought in your heart saying, The seventh year, the year of release is at hand and your eye be evil against your poor brother and you give him nothing and he cry out to the Lord against you and it become sin to you, you shall surely give it to him” (Deuteronomy 15:9-10 NKJ).

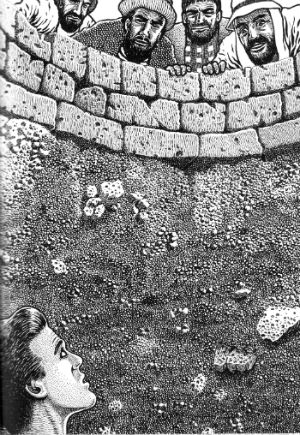

Even the Patriach Joseph experienced slavery. (Basil Wolverton artwork)

Even the Patriach Joseph experienced slavery. (Basil Wolverton artwork)Not only that but after reemphasizing the freedom granted in the Year of Release came these words:

“And when you send him away from you, you shall not let him go away empty-handed, you shall supply him liberally from your flock, from your threshing floor, and from your winepress” (Deuteronomy 15:13-14). This is called “setting up the servant with a stake,” investing in his future success. After this warning against “hard-heartedness and tightfistedness” (verse 7 – NIV) came the pivotal statement that showed where Yahweh, God of Israel, was coming from when slavery was address, the context: ”You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt and the Lord your God redeemed you” (verse 15).

Now we know why individuals under servitude were to be treated humanely and with a potential for release fully in view. It was traced to the character of Yahweh. In fact it is from this keynote text of Yahweh as Liberator and Freer of the Oppressed – the One who brought Israel out from Egyptian bondage – that the humane treatment of servants and slaves derives its moral force all across Torah. There are other examples.

After reemphasizing that the hired workers were to be freed in the Jubilee Year (every fifty years) came this injunction: “If your brother becomes poor take no interest from him nor profit, but fear your God so that your brother may live beside you…he shall be with you as a hired worker and as a sojourner. He shall serve with you until the year of Jubilee. Then he shall go out from you, he and his children with him and go back to his own clan and return to the possession of his fathers. For they are my servants whom I brought out form the land of Egypt, they shall not be sold as slaves. You shall not rule over him ruthlessly but shall fear your God” (Leviticus 25:36-43, ESV).

Once again, Yahweh the Liberator has spoken and reiterates the Law’s bias to regulate and moderate the institution. By not charging the servant interest on loans they had a better chance of getting back on their feet.

Commentators know that there was another kind of slavery in Torah – that involving captives taken in war. Leviticus 25:44 underlines that this statute which allowed Israelites to buy slaves of the surrounding nations and even from immigrant families was also hedged about with controls and regulations. As part of the general rule allowing plunder and enslavement of the women and children of a captured city, Deuteronomy 21:10-14 cited the case of an Israelite attracted to a woman taken captive. If after a brief interval the woman was no longer appealing to the man, “you shall let her go where she wants. But you shall not sell her for money, nor shall you treat her as a slave, since you have humiliated her.” This Bronze Age concern for human rights and dignity puts to shame some of the laws on the books even in the United States before 1865.

Other statutes clearly point to the humanitarian bent of the Law. Slaves were allowed to rest on the sabbath (Exodus 20:10); a Hebrew worker was still called a brother (Leviticus 25:39); the slave could be avenged or even freed in cases of unusual or harsh treatment (Exodus 21:26-27); and escaped slaves must not be returned (Deuteronomy 23:16-17).

The evidence seems clear. Like a salmon swimming upstream, God’s laws relating to slavery contain more than a hint of where the compassionate God of Israel was eventually heading. Though he made accommodation to Israel for its hardness of heart (Matthew 19:8) and for being unable to escape the customs of the nations, the Great Commandment to love your neighbor as yourself was already on the way to its greater formulation under Jesus (Leviticus 19:18). There is surely where Yahweh’s basic intention was pointing.

As Willard Swartley (pictured, left) argues in his eye-opening volume Slavery, Sabbath, War and Women: Case Issues in Biblical Interpretation, much of the Torah is essentially “descriptive” as well as “prescriptive.” That is, it shows how God helped Israel to operate in a crude and dangerous Bronze Age nation that had itself just escaped from slavery. Humanitarian concerns were consistently spelled out against the powerful background reminder that “you were once slaves in Egypt.”

Swartley adds, reaching into the New Testament: “Slavery advocates dare to say that the prophets and Jesus never spoke against slavery, thereby condoning it. We have already seen the absurdity of that argument in that piracy, arson and twenty other heinous sins are therefore condoned” (page 51).

It is thus possible to “rightly divide the word of truth” once bitter emotion and prejudices have been set aside. God is the Great Liberator in both Testaments. Long may he reign.