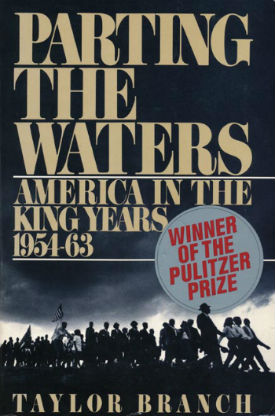

Arrest of Mrs. Malcolm Peabody in St. Augustine, Florida.

Arrest of Mrs. Malcolm Peabody in St. Augustine, Florida.By Neil Earle

Black History Month is a good time to remember how five decades ago a group of Christian churches – mostly black at first – led the way in ending the legalized racism of this nation and helped ignite the end of America the Segregated, the world of Driving Miss Daisy.

A USC professor participating in a Black History Event in our Glendora congregation in 1997 focusing on these events said he was now able to answer his black students (!) who claimed Christianity was a “white man’s religion.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s pastoral background had belied that accusation as did those of his close supporters – the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, the Reverend Andrew Young, and the Reverend James Massey. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) formed by these youthful churchmen spearheaded the anti-segregationist crusade. Their target was the unjust laws legally forbidding African-Americans to drink at public drinking fountains or eat in a public restaurant or lodge in a decent hotel in many parts of America.

Almost 100 years after Emancipation those walls would come tumbling down.

Black History Month can teach us many lessons but maybe the one we need to take away today in 2013 is that people can change, nations can change, laws can change. In a time of political paralysis and bitter division we could do worse than reflect on how real, effective change can come when the grass roots of the population is well-led and fully mobilized and given a clear moral agenda to follow. In the 1950s and 1960s most of that leadership came not from the Congress or from the courts but from the churches. Dr. King was not slow to praise his allies in the Christian communities:

“But again I am thankful to God that some noble souls from the ranks of organized religion have broken loose from the paralyzing chains of conformity and joined us as active partners in the struggle for freedom. They have left their secure congregations and walked the streets of Albany, Georgia with us. They have gone down the highways of the South on tortuous rides for freedom. Yes they have gone to jail with us. Some have been dismissed from their churches, have lost the support of their bishops and fellow ministers. But they have acted in the faith that right defeated is stronger than evil triumphant” (Why We Can’t Wait, page 92).

Using a skilful combination of peaceful protest and non-violence, the civil rights movement slowly began to move towards the SCLC goal – to subpoena the conscience of the nation.

But it was never easy. Bloodshed and violence met those protestors at virtually every turn. Nor did it spare the children.

Just as in Montgomery earlier, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama had been a rallying place for the civil rights movement all throughout 1963.

On Thursday, May 2, a line of fifty teenagers, well-trained in non-violence, emerged from Sixteenth Street Baptist Church singing hymns. The police were waiting for them and hauled them into paddy wagons until a second line emerged from the church and then a third. Amid mounting confusion police commanders called in school buses as jail transport and sent reinforcements to chase after singing youth headed to the downtown district to protest segregation.

“We are not afraid/ we are not afraid…O deep in my heart/ I do believe/ We shall overcome some day.” Those singing children converted many doubters in Birmingham and around the nation…and the world.

Revenge was forthcoming. Sunday, September 15, 1963 was Youth Day at Sixteenth Street Baptist. Mamie Grier, superintendent of the Sunday School, met four young girls who had just left Bible class talking excitedly about the new school year. All four were dressed in white from head to toe ready for the 11 o'clock service. Mamie Grier urged them to hurry along and went upstairs. A few minutes later a loud bomb blast shook the entire church. Amid moans and sirens schoolteacher Maxine McNair stumbled through the smoke searching for her only child, sobbing. She soon met a weeping old man. "I can't find Denise," she blurted out. The man replied: "She's dead, baby, I've got one of her shoes."

All four girls from the basement died that day.

Later that day Maxine McNair's husband, Chris, returned from the morgue, grief-stricken. He entered a store shopping for items needed for the funeral. Everywhere white sales clerks burst into tears, saying they had seen him on television. That same afternoon dignified, overwrought white strangers knocked at his door to express their extreme sorrow. Some of them arrived in cars bearing Confederate plates.

The world was stunned at the news from Birmingham but that afternoon Chris McNair unknowingly muttered a prophecy: "Maybe her death will do some good."

It did do good. A lot of good. 8000 people braved the vigilantes and jeep patrols to attend Birmingham's largest funeral. Among the mourners were 800 Birmingham pastors of both races, making Denise's funeral the largest interracial gathering in the city's history. The Christian conscience of the nation was being aroused. As Dr. King wrote later:

“Nationally renowned religious leaders were taking their place in jail cells along with the ordinary Negro. Sitting in [the] patrol wagon between the Negro domestic and the truck driver was the erect figure of the head of the Presbyterian Church. Catholic priests and rabbis of Jewish congregations took their places on the front lines as the Old and New Testament ethic of social justice flamed with the fire that once before had transformed the world” (page 118).

Arrest of Mrs. Malcolm Peabody in St. Augustine, Florida.

Arrest of Mrs. Malcolm Peabody in St. Augustine, Florida.This was literally true. The times they were a-changin' indeed.

It was the support of allies from the dominant culture that helped turn the tide.

Mary Parkman Peabody was the bluest of Boston bluebloods. A grandmother seven times over, her husband was a respected Episcopal Bishop of New York, her son the Governor of Massachusetts. On March 29, 1964 she was in Florida determined to help integrate the stubborn city of St. Augustine. Driving from the airport with civil rights leader Hosea Williams, Mrs. Peabody calmly exclaimed: "I do not believe the local authorities will deny me the pleasure of lunch with my Negro friends."

Williams replied: "Mrs. Peabody, these folk will deny Jesus."

Mrs. Peabody attempted to integrate the all-white Trinity Episcopal Church that Sunday. She found the doors locked and the sheriff standing guard. Later that day news came to her that her good friend, Esther Burgess, the wife of the black Bishop of Boston, had been arrested. Mrs. Peabody was asked: Would you be willing to join Esther in jail for maximum publicity. She said, yes, but none of the men were willing to go with her. Up spoke Georgia Reed, a small, short seamstress with a leg crippled by polio: "I'll go."

The Bishop's wife and the Seamstress were soon duly arrested before being escorted off the premises of the Ponce de Leon Motor Lodge – Peabody for fraternizing with "undesirable guests." Georgia and the Bishop's wife entered the overcrowded jail where 57 black women were held in a cell with only four beds.

One of the ladies gasped at the sight of the well-dressed Mary Peabody striding elegantly to the "whites only" section of the penitentiary: "You look just like Eleanor Roosevelt."

"We're cousins," Mrs. Peabody proudly replied (See Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire.) After two nights in jail she refused to be released until all 117 other activists were freed as well.

This was news and showed how individual efforts mattered greatly. SLCL leaders as public theologians couldn’t do it all. But through marches, boycotts, sit-ins, and with the thunder of their voices, they hammered out a brisk and daring new theology of social action. The nation's TV networks became pulpits and the jails their classroom. Thus, from the churches as recruitment centers and meeting places and spiritual armories that there came the greatest challenge to the moral crisis of racism in the United States and the world ever mounted. You could tell it from the songs of the marchers and protestors – old hymns became converted into anthems, “We shall overcome,” We shall not be moved,” “O Freedom.”

LA Times correspondent and Pulitzer Prize winner Hector Tobar.

LA Times correspondent and Pulitzer Prize winner Hector Tobar.The country was changed – really changed. The landmark Civil Rights legislation of 1964 and 1965 is still being debated as to its full application but there is little doubt that it marked America's public repudiation of segregation as an organized system.

We still live in a time of racial tension. Ours has been described as a time of racial and moral fatigue. That is why we need reminders. One man who understands this is a Pulitzer Prize winner and Los Angeles Times correspondent named Hector Tobar (pictured, right). As he told an audience in Duarte, California recently:

“Like thousands of other Angelinos, I am the son of immigrants. I thus owe my citizenship to Dred Scott, a slave who sued for his freedom in 1857 and to Frederick Douglass who took up his cause.” The Republican Congress that passed the Fourteenth Amendment granting citizenship to anyone born in America means, says Tobar, “that the children of Mexicans and Central Americans are the chief beneficiaries.” The long African-American struggle for civil rights, he concluded, “has blossomed into an oak tree of justice whose large canopy protects all of us, no matter our color.”

Well spoken words. All Americans need to know how history can speak to us today – change is possible. Christians can remember that there are time when actions are required that go beyond churchly platitudes

(Racial reconciliation is an important theme in our congregation. Read more on this subject at atimetoreconcile.org.)