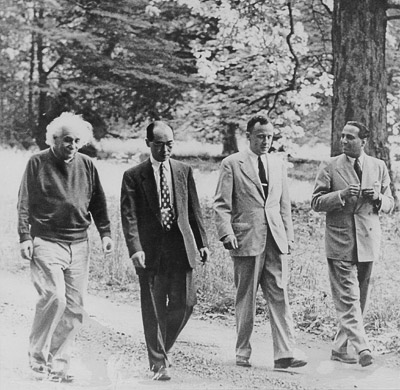

At Princeton: Einstein at left, John Wheeler third from left.

At Princeton: Einstein at left, John Wheeler third from left.By Neil Earle

In 1964 a particle physicist named Peter Higgs postulated an answer to the scientific question, Why does matter exist?

In an era when science was agreeing more and more about the basic subatomic particles that made up the Standard Model of Physics, it was irritating to have one major stone unturned: the explanation of how the energy that pervades the Universe could be converted into mass. Then Higgs argued that particles gain mass by passing through an energy field. In common parlance, the field sticks to the particles and slows them down like a football player carrying the ball being tackled on a crowded field.

As The New York Times explained: “The Higgs boson (a non-spinning particle) is the only manifestation of an invisible force field, a cosmic molasses that permeates space and imbues particles with mass.” The missing element became dubbed the “Higgs boson” or in popular legend, “the God particle.”

Last week, the CERN multinational research center headquartered in Geneva announced they had found it – the Higgs boson. Finding it is a major victory for the giant Hedron collider in Switzerland. John Gunion, at UC Davis, was satisfied that the new particle was associated with the production of mass in the Universe in the moments after the Big Bang (LA Times, July 5, 2012).

In 1993 Noble Prize Laureate Leon Lederman had written a book entitled The God Particle which explained how important it was to crack this mystery closely tied to the origins of matter. That is why some Christian folk were intrigued when the Higgs discovery was named “the God particle” in early reports. While some church-goers were amused other theologians of a more scientific bent took exception to that description. God is not present in the Universe he created, went the rebuttal. That is pantheism. God towers above all that is made. Job 11:7 said we cannot by searching find out God – not now, not ever.

Nevertheless discussions followed in some church congregations last week. The Higgs boson finally showed up – at least to about 99% certainty. Some still have their doubts. But the theme of Science and Religion once again re-emerged in the news.

Today we tend to give Science the seat of honor at the intellectual banquet. The Christian church’s persecution of Galileo (1564-1642) and slowness to admit the earth was round in the 1600s, these were two factors causing religion to lose clout as the Enlightenment of the 1700s and the Darwinism of the 1800s seemed to land more body blows on the way most people had read the Bible. Science and its offspring – applied technology – grabbed the spotlight from Religion and began to gain even more prestige with the Space Race, the computer, heart and kidney transplants and now smart phones connecting the world. But how strange. Strange because the first evidence that was coming in from the New Physics – roughly, everything after Einstein’s first Relativity paper in 1905 – was moving in a different direction. The new subatomic world (it took Einstein to even confirm the existence of atoms) was “not uncongenial to religion” in the words of the great Edinburgh theologian, Thomas Torrance (d. 2009).

At Princeton: Einstein at left, John Wheeler third from left.

At Princeton: Einstein at left, John Wheeler third from left.It’s often forgotten today how Albert Einstein (1879-1955), born of German Jewish parents, continually referenced God as Der Alte (the Old One). In his mind, at least, Science and Religion did not live in watertight compartments. In fact, the greatest physicist of them all could be described as something of a religious mystic at heart. A Swiss biographer reported: “Einstein used to speak of God so often that I almost looked upon him as a disguised theologian.”

Einstein would have vociferously disagreed with the recent conclusion of Noble Laureate Stephen Weinberg that “the more the universe seems comprehensible the more it seems pointless.” Einstein’s fascinating legacy included such statements as: “The deeper one penetrated into nature’s secrets the greater becomes one’s respect for God.” Many such observations are included in Thomas Torrance’s provocative work Theological and Natural Science. As a leading proponent of Scientific Theology, Torrance believed that at their core, science and theology are closely linked.

Torrance was also a close friend of the brilliant Princeton physicist John Archibald Wheeler (1911-2008). Wheeler had helped formulate “Black Holes” in addition to working on the Manhattan Project in the 1940s. Wheeler and Einstein were collaborators at Princeton in the 1950s. Perhaps because of Einstein’s influence, Wheeler was inclined to take a more metaphysical view of science, the Los Angeles Times reported (July 5, 2012, E9). Einstein and Wheeler were first wave New Physicists who believed, in the words of chemist Walter R. Thorson, that Science was based on faith: “The practicing faith of a scientist is a faith ultimately in the order, consistency, and intelligibility to man of the creation in which we find ourselves…in a dependable Creator.”

The Los Angeles Times (July 5, 2012) was correct to note that “when we ask why there is something rather than nothing at all, we are, unwittingly or not, heirs to a way of thinking that is a vestige of early Judeo-Christianity.” For Christians, Einstein’s “Old One” was the Logos of John’s Gospel, Chapter One, without whom nothing was made that was made. Indeed, it is from the Greek “Logos” that we get the very world “logical.” Einstein said something similar in his answer to a young girl’s question if scientists ever prayed:

“Scientific research is based on the idea that everything that takes place is determined by laws of nature…However, it must be admitted that our knowledge of these laws is only imperfect and fragmentary, that actually the belief in the existence of basic all-embracing laws of nature also rests on a sort of faith.” Einstein believed that much of this faith has been evidenced, but, on the other hand, “everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe, a spirit vastly superior to that of man” (Torrance, Theological and Natural Science, page 26).

In the face of the complicated precision of the universe he concluded that “the pursuit of science leads to a religious feeling of a special sort.”

Einstein thus spoke with much more humility on Science than is noised about from hasty discussions on quickie TV interviews, the printed press or far too many textbooks. Too often a short-sighted, breathless headline appears such as “’Universe has no Purpose’ says Leading Scientist” and – bang – the old Science/Religion bun fight is on again.

The orderly universe which Einstein believed came from God’s hand, nevertheless required immense mental labors to decipher. Einstein’s early religious upbringing may have made him receptive to the thought behind such texts as Isaiah 45:15, “Truly, you are a God who hides himself.” And Proverbs 25:2, which says, “It is the glory of God to conceal a matter; to search out a matter is the glory of kings.” Einstein often gaped at “the mysterious comprehensibility of the universe which is yet finally beyond his grasp” (Quoted in Torrance, Theological and Natural Science, page 31).

“To know the mind of God” – that, according to Leon Lederman was one of Einstein’s chief motivators (The God Particle, page 24). Nature’s secrets, its hidden order and mysteries, could not be derived from surface study alone but from “tapping into the thoughts of God.” Einstein added: “Science can only be created by those who are thoroughly imbued with the aspiration towards truth and understanding. This source of feeling, however, springs from the sphere of religion” (Science, Philosophy, and Religion).

So there it is. Einstein was astute enough – and humble enough – to testify that Science and Religion needed each other. Though Einstein did not view God as a personal Being in the evangelical Christian sense – he feared the distortions that arise when we try to “exploit” God – he acknowledged the Old One, the Superior Reasoning power behind all things. This led to his much-heralded 1939 statement: “Science without Religion is lame; Religion without Science is blind.”

Professor Tom Torrance’s insights built on Einstein’s and Wheeler’s in combination with Christian theology. It was understandable why many scientists are reluctant to consider the thought of a Creator whose intellect towers above the Universe he established. Finding particles can be an exhausting, time-consuming project. Torrance’s answer was a creative one indeed. “The universe has an orientation both away from and towards God” Torrance argued in such works as Divine and Contingent Order. “It is both dependent on and independent of God, endowed with its own autonomous order.” This partly explains why the minute details of the superbly constructed creation – visible and invisible (Colossians 1:17) – are so hard to pierce.

“This is the signature of the Creator,” adds Torrance. “The creation’s capacity is to spontaneously generate richer and more open-structured forms of order in the constantly expanding universe.”

Torrance did some hard thinking along these lines. His conclusions offered an advance on ideas far beyond the Cosmic Watchmaker idea of the “Clockwork Universe” of Newton’s disciples. In this scheme, God often got lost, so to speak, in the machinery of the Old Physics. No, said Torrance, there are enough surprises and noises inside the created order both to challenge human creativity and point to Einstein’s belief in a Superior Intelligence – the Old One – behind it all.

Seen this way, Torrance’s thoughts seem very pertinent in this milestone week for physics. The Universe is open to surprise and investigation, Torrance maintained. With its rationality, the created order is a matter-based parallel to and gift from the Logos, the invisible power behind it all (Hebrews 11:3). What we see is not a closed-off constrained world system but one that is developing, capable of surprise and innovation in a way that points beyond itself to something greater. Perhaps it is Christians, more than scientists, who need to investigate further.