By Neil Earle

As the season called Easter draws near, most Christians will participate in a bread and wine ceremony that is noteworthy for the different names it is given in the Bible – communion, the Lord’s Table, the Lord’s Supper, the cup of Blessing, Passover, the Breaking of The Bread and even “love feasts.”

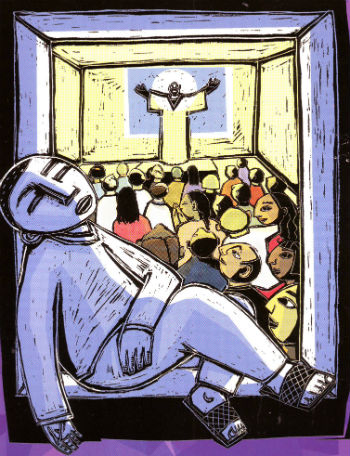

This variety of terminology not only underscores the flexibility surrounding the Christian sharing of bread and wine. It also underscores the tremendous “liberty in Christ” that marks the Christian religion. The Holy Spirit that leads the followers of Christ is marvelously fluid and dynamic. He will never fit neatly inside a box. The new faith was wonderfully exportable and “made to travel” (Acts 1:8). Christianity is not bound to certain fixed places or geographic spots such as Sinai, Jerusalem, Mount Gerizim, Qumran, Mecca or even Rome and Canterbury. The Spirit, like the wind, “blows wherever it pleases” (John 3:8) making this flexibility one of the hallmark traits of Christian ceremonies, as opposed to the fixed nature of the Old Testament system it replaced.

Regularly taking the bread and wine “whenever you do it” as an act of remembrance of Jesus Christ as the living activist Head of God’s people on earth, this ceremony in particular pulsates with overtones of spiritual power and memories of deliverance from death. Two scenes which follow from the Biblical narrative bring this out. This sermon will focus on the phrase “Breaking of the Bread,” the technical term in both Acts 2:42 and Acts 20:11.

A good way to start is to ask: Does Christianity really work in “the real world?”

We ministers hear this kind of question often.

If we turn to Acts 27 we find Paul near the climax of his life-threatening sea journey to Rome for trial before Nero. Paul, Luke and Aristarchus and 273 other travelers on a huge grain ship from Alexandria have been driven by wind and storm for two weeks. God had revealed to Paul that they would be saved (Acts 27:25). Then Paul did something remarkable for the context. In the face of this furious storm raging around them he urged the crew to take something to eat for their physical strength while he himself did something unexpected, considering the howling storm about them:

“After he said this, he took some bread and gave thanks to God in front of them all. Then he broke it and began to eat. They were all encouraged and ate some food themselves. All together there were 276 of us on board” (Acts 27:35-36).

There is a dignity and richness to the King James Bible’s version of this scene that has led many Christian teachers to conclude that Paul is actually imitating here a shortened version of Jesus’ Last Supper with his disciples. “And when he has thus spoken, he took bread, and gave thanks to God in presence of them all; and when he had broken it he began to eat (KJV).” This seems to clearly echo Luke 22:19 where it is mentioned of Jesus: “And he took bread, and gave thanks, and brake it and gave unto them, saying, This is my body which is given for you; do this in remembrance of me.”

Both the conservative Methodist teacher, I. Howard Marshall, and the Anglican scholar F.F. Bruce do not think Paul is necessarily celebrating a Christian Lord’s Supper here. But even Marshall concedes that”the language which is used by Luke is probably deliberately intended to remind his readers of the meals held by Jesus and of the Breaking of Bread in the church…The meal is one in which the saving and sustaining power of God is acknowledged and praise and thanks are offered to him for his goodness” (Last Supper and Lord’s Supper, page 130).

The Catholic writer Eugene LaVerdiere summarized even more the implications of Paul’s actions in Acts 27: 35. LaVerdiere writes that “eating something is necessary for salvation…The bread that Christians break is the bread of salvation….Just as the bread they took assured their survival at sea, participating in the breaking of the bread would assure Luke’s readers of their own Christian salvation” (The Breaking of the Bread, pages 220-221).

Both before and after his death Jesus ate in the presence of his disciples (Luke 20:19; 24:30). As we shall see, the communal meals of the early Christians were rife with strong overtones of God’s presence moving mightily for their ultimate salvation as well as their real-life preservation here on earth. We see this brought out more concisely in the next scene, one that involves a resurrection from the dead.

This event occurred in Troas, a city near the crossroads between Greece and Turkey. Once again Paul is the chief player. Luke says, “On the first day of the week we came together to break bread.” Now the expression “first day of the week” was loaded with overtones of resurrection power for the early Christians. It was “on the first day” that the women came to the empty tomb (Mark 16:2). The same day the resurrected Lord appeared to Mary Magdalene, Peter and the two disciples on the Emmaus Road. Jesus greeted all his disciples later that same day at evening. It was when the two disciples on the road to Emmaus saw Jesus break the bread for supper that they knew it was him (Luke 24:30-31). Later that day, Jesus ate the broiled fish in the presence of the disciples to show he was still alive (Luke 24:42).

Once again, eating something in community is a reminder that you are in the presence of the resurrected Lord, the One who has all power and authority. In Troas a crowd of Christians were gathered on the first day of the week to break bread, and here it means to share a meal. Paul’s speech went long. A young man named Eutchyus fell from the third story. But then something dramatic happened:

“Paul went down, threw himself on the young man and put his arms around him. ‘Don’t be alarmed,’ he said. ‘He’s alive!’ Then he went upstairs again and broke (the) bread and ate. After talking until daylight, he left. The people took the young man home alive and were greatly comforted” (Acts 20:10-12).

As LaVerdiere and others have seen, this brief incident is alive with references that conjure up salvation. The Breaking of the Bread is distinguished from mere eating – “breaking bread.” The word “zonta” for alive in Eutchyus’ case is exactly the same word used for Jesus the “living one” in Luke 24:5. Acts 1:3 states Jesus showed himself alive (zonta) after his passion. On this first day of the week, young Eutchyus participated in the new creation, enjoying a resurrection already! The whole community rejoiced at this and had it reinforced soon after.

By now we discern that there is something special about this phrase “the breaking of bread.” Some Greek texts refer to it as “the breaking of the bread.” Obviously this practice meant more than sharing a common meal. It was an integral part of what Marshall identifies as the four elements of a typical gathering in the early church. Acts 2:42 shows them doing four things: They heard the disciples teaching; they prayed to God; they enjoyed fellowship, they broke bread together. I. Howard Marshall explains the breaking of the bread as “the action at the opening of a meal, the actions which Jesus had invested with special significance.”

The picture of Jesus eating with his disciples is one of the most famous religious depictions in history. But the special significance escapes most people. The last Supper became the Lord’s Supper. “Here, then,” writes Marshall of Acts 2:42, “we have reference to the Lord’s Supper. If this interpretation is correct, the common meal is here distinguished from the breaking of the bread, and we would have the same picture as in 1 Corinthians where the Lord’s Supper proper took place in the context of a fuller meal held by the congregation.”

The pesky Corinthians turned the “Lord’s Supper” into a carnal banquet where the rich looked down on the poor (1 Corinthians 11:20). The implication is that in Corinth Paul’s converts were imitating Jesus’ actions at the Last Supper fairly regularly. But through selfish attitudes they were missing the deeper spiritual insights that had ignited the faith of the two Emmaus-bound disciples. They were thus missing the reenacted assurance of God’s resurrection power to deliver us. This is why Paul commented that many were sick and some had died (1 Corinthians 11:30).

Yes, spiritual insight, divine power and supernatural deliverance together with the revitalized sense of spiritual life from partaking the emblems of Jesus’ sacrifice – all these are tied up in the meaning of the Lord’s Supper, the Breaking of the Bread. Luke traces this back even further to the only miracle mentioned in all four gospels. This was the feeding of the 5000 mentioned in Luke 9. On that occasion, the disciples who started the meal with nothing ended up with twelve baskets full of bread left over (Luke 9:17). Those twelve baskets symbolized the twelve disciples going forward to offer Jesus Christ as the true Bread of Life to this hungry world.

That feeding, that spiritual nourishment still goes on and it takes its motivation and impetus from those times when Christians gather in his name to break the Communion bread and eat it in His name. Let’s continue to do so and reap the benefits and blessings.