By Neil Earle

“The kings’ heart is in the hand of the Lord, as the rivers of water; he turneth it whithersoever he will” (Proverbs 21:1).

Mention “the Bible” and for millions of people around the world it is still the King James Version (KJV) or Authorized Version (AV) of 1611 that springs to mind. This year, 2011, marks the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible, perhaps the most successful book ever printed.

It has been said that how we got the Bible is almost as fascinating as its message. The King James Version confirms this observation.

For starters, 1611 was almost a full century after the Protestant Reformation. This was a time of explosive interest in theology. Camps of doctrine were forming and reforming all through the 1500s and people wanted to argue from Bibles produced in their own languages. In 1611 the most popular Bible among Englishmen was the Geneva Bible of 1560. It was the work of a group of English refugees in Switzerland fleeing the reign of the infamous “Bloody Mary” Tudor in their home country (1553-1558). The Geneva Bible was a good piece of work but famous for its marginal notes that took potshots whenever possible at kings and queens, rulers and magistrates calling them “tyrants.” This made it a favorite of English “Puritans” – a loose group of religious zealots trying to purify the Church of England of its Catholic trappings.

When Elizabeth I took over in 1558 she ordered a translation to meet the needs of her more moderate Anglican worshippers. The result was the Bishop’s Bible of 1568, a good work but too scholarly and intellectual for the man and woman in the pew. For example, the Bishop’s Bible translated Psalm 23:2 as “he will cause me to repose myself in pasture full of grass.” And so when James VI of Scotland became James I of England in 1603 the stage was unwittingly being set for a new translation of Scripture.

This significant event occurred almost as an afterthought. In 1604 James convened a conference at Hampton Court where the king and his bishops tried to discipline the contentious Puritan dissenters.

Tension reigned. Then, Dr. John Reynolds, a moderate Puritan, proposed that a new translation be made of the Bible in English for both private and public worship. King James himself had exalted ideas about the role of kings and rulers and wanted nothing to do with the Geneva Bible. He especially wanted a new translation that would “read well” in the churches. This project also appealed to the scholarly interests of the new King, a published author in his own right. In a still largely illiterate age, a Bible that would convey royal dignity and controlled majesty when read aloud might help the king’s cause. James gave the task his blessing and eagerly.

Studious compromise was to be the hallmark of the King’s translation. Officially, at least, the KJV was to be a revision of the 1602 version of the Bishop’s Bible, but at least 80% of its style and sense in the New Testament came from the pen of a man who had been earlier executed for sending printed Bibles into England. His name was William Tyndale and his 1525-26 translation of the New Testament was admired by all. When we read phrases such as “sounding brass and tinkling cymbal,” or “the twinkling of an eye” it is Tyndale’s pictorial, colorful and yet descriptive English we are reading. The Geneva Bible also played its part. It echoes in such typical “King James” phrases as “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want” and “beside the still waters.”

Even the earliest complete English Bible – Wycliffe’s handwritten version of the 1300s – leavened the 1611 Version. Such clear and meaty Anglo-Saxon as “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” and “many be called but few be chosen” date back to the work of Wycliffe’s band (1329-1384).

The King James translators thus had great respect for what had gone before. The new Bible was to be very much a product of “the whole Church” more than of any one group. One of the 48 or so translators (some died and had to be replaced) even had contacts with learned Jesuit scholars. English-speaking Catholics were even then busy on the Rheims-Douai Version. One KJV man was an expert on Islam. The 16 Rules for the translation process were clearly laid out by the king himself. “Faire and softly goeth far” was the formula behind the KJV’s harmonizing of extremes, its spirit of lively compromise and the deep respect for what had gone before – all hallmarks of the 1611 project. Today we joke that “a camel is a horse designed by a committee” but here is one piece of consensus that really worked:

“Three panels worked on the OT (Genesis to 2 Kings, 1 Chronicles to Ecclesiastes, Isaiah to Malachi), one panel did the Apocrypha, and two panels worked on the NT (one did the Gospels, Acts and Apocalypse, the other did all the Epistles. Two of the panels met at Oxford, two at Cambridge, and two at Westminster” (David Ewart, From Ancient Tablets to Modern Translations, page 199).

The process involved was quite “modern” in the sense that the work was farmed out in organized sections. The final revisions were to be made by twelve of the committee members – two from each panel – and their work sent to the King and the Archbishop. This final stage was described by a friendly lawyer:

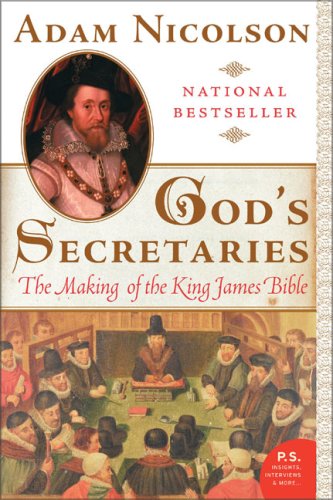

“…that part of the Bible was given to him who was most excellent in such a tongue [Greek, Hebrew or Aramaic]…and then one read the translation, the rest holding in their hands some Bible, either of the learned tongues [Hebrew or Greek] of French, Spanish, Italian, etc. If they found any fault, they spoke up; if not, he read on" (Nicolson, God’s Secretaries, page 209).

There was thus nothing hasty or haphazard about this process. The translators were James’ “dream team” picked from the most devout and learned men. Chief Translator Lancelot Andrews, the King’s Chaplain, could speak 22 languages. All were conscious that they were in a long and honorable line of workers – from Wycliffe, Erasmus, Tyndale, down to the 1560’s efforts. A surprising humility reigned. As Miles Smith wrote in the “Preface,” these scholars never felt they were doing a perfect job but attempting “to make a good translation better.”

There’s a lesson here for us. It is shortsighted to exalt the 1611 version above all others. Any attempt to render in today’s English a book containing thoughts and concepts that go back to Ancient Iraq and early Egypt will be bound to have flaws and defects. But by having a sincere goal “to make God’s holy truth to be yet more and more known” the men of 1611 pointed future translators in a right direction. Various “learned men” across the kingdom were also to be consulted when difficulties arose.

Even with a project of such size and scale, the spirit of consultation and counsel succeeded. This made the KJV a pattern-setter for the ecumenical and wide-ranging translations that followed in the 20th Century. Doctrinal debate and conflict had actually sharpened men’s minds and improved scholarship immensely. Literacy rates were rising. No one wanted to be proved wrong on the basis of a poorly translated text

An exemplary balance was achieved. Project director Lancelot Andrews was a firm believer in the ceremonial trappings of Anglicanism. Yet there were enough stalwart Puritans among the six committees to lend the work a strong evangelistic flavor. Smith’s Preface urged zeal in “maintaining the truth of Christ and spreading it far and near.”

And so the work was done. Only little room was afforded to private or personal leanings. The balance between Anglican bishops, Puritan zealots and some merchant/ministers ensured that no one doctrinal slant would dominate. This was rare in 1611…and today. Catholic input aside, the King James Bible was perhaps the most ecumenical project Protestant Europe had yet seen. The goal of a Bible “that readeth well” was achieved.

The KJV’s linguistic richness and subdued majesty reflected the age of kings when monarchs ruled. Where today we might say, “Here is what the Lord says,” the King James crisply announced: “Thus saith the Lord.”

Of course the work had to be regularly edited and updated. A 1631 edition left out the word “not” in the Seventh Commandment (Exodus 20:14) and was thus branded “the Wicked Bible.” These linguistic updates across the centuries explain why so many variations crept out into the world. Some even claim that no one thing such as “the King James Bible” has ever existed (Nicolson, page 226). Still, nothing detracts from the KJV’s rhythmic power, the elegant balances in such phrases as “Our father which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name,” the warmth of “Daughter, they faith hath made thee whole” or the memorable force of “Jesus wept.” These texts showed the harmony and beauty of the old amid the new, according to the King’s own instructions.

Such 1611 phrases as “bring hither the fatted calf,” and “my cup runneth over” breathe the spirit of Wycliffe’s time, of an age when feasting was all the more precious because it was so rare. Emerging from the age of Shakespeare and Walter Raleigh, the 1611 Bible reflected the bent of scholars accustomed to pungent, punchy phrases such as “Physician, heal thyself,” or “See that you be not troubled.” Though it took a while to catch on, the KJV was almost destined to be a hit. The literary critic Peter Ackroyd claimed that the new Bible “invigorated the consciousness of the nation” and through the spread of the English language it positively affected the rest of the world. It is not too much to say that the Authorized Version gave a centrality and a commonality to Christianity that endured until very recent times. There is a lesson here too: The new is not to be easily tossed aside because it is new.

The Authorized Version thus deserves its 400th anniversary celebration. The men of 1611 knew that their new Bible was not handed down magically by angelic hands from heaven. They presented their new translation to the church “with all humility” never imagining that some misguided descendants would feel they had produced the “one true text.” In fact, their attitude of being open to fresh inputs and insights from the Holy Spirit and each other is a precious legacy for us today, we who are also challenged to be led by and updated by the Spirit of Wisdom. For that reason alone, Happy Birthday, King James Version.

— Neil Earle