The author with wife at King James Bible exhibit at the Duarte Library. (Photo by Alan Heller)

The author with wife at King James Bible exhibit at the Duarte Library. (Photo by Alan Heller)By Neil Earle

The author with wife at King James Bible exhibit at the Duarte Library. (Photo by Alan Heller)

The author with wife at King James Bible exhibit at the Duarte Library. (Photo by Alan Heller)This week down the road here in Glendora, CA the good folks at Azusa Pacific University are shutting down their month-long tribute to the 1611 King James Version of the Bible. That’s on November 21. They’ve had lectures, oratorios, media displays, panel discussions and well-stocked exhibits paying tribute to what is probably the world’s best-seller.

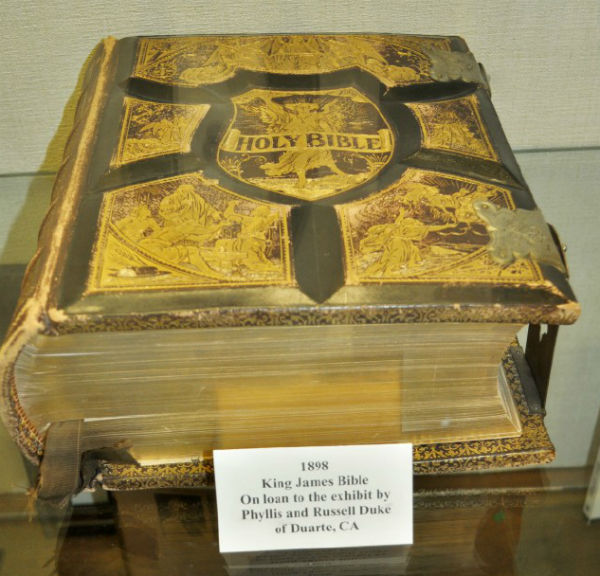

Our local church has been involved in the year-long celebrations and even sponsored a small exhibit on the history of the KJV at my home-town library in Duarte, CA.

We could use the hackneyed phrase “the legend continues,” I suppose, for even when attending English classes at UCLA Extension it was easy to find support from professors aware of the claim made by literary critic Peter Ackroyd in Albion: The Origins of the English Imagination (2002) that the King James Bible “invigorated the consciousness of the nation.” 1

That’s quite a claim for a most literate country proud of its literary heritage. “In the beginning was the word” but in English-speaking countries that word has taken on a very definite shape and tone. Of course I mean the celebrated cadences of the King James Bible, (“Comfort ye, comfort ye my people,” “eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth”) a literary masterpiece that reflected a century of bloody struggle and intellectual acuity. The result was a translation of such beauty and popularity that one of the Pope’s ambassadors in those dire days of Protestant-Catholic tension praised (somewhat left-handedly) the English Bible as a living force. “It lives on the ear like a music that can never be forgotten, like the sound of church bells, which the convert scarcely knows how he can forgo. Its felicities seem often to be almost things rather than words. It is part of the national mind, and the anchor of the national seriousness.” 2

The good father went on to add that the King James Version was “one of the strongholds of heresy in this country.”

Relax. I am not a King James idolator. I prefer the New King James or the New English Bible myself but no advertisement for Bible-reading can improve upon the judgment allegedly offered by Napoleon Bonaparte, a man otherwise not known to be a Bibliophile. “The Bible is no mere book, but a Living Creature with a power that conquers all who oppose it.” 3

My esteemed UCLA professor, Carolyn Chiapelli, agreed with the quote that emblazons Lawrence Nelson’s splendid 1946 effort, Our Roving Bible, that the Bible is “a book-making book. It is a literature which provokes literature.” Nelson added for good measure the fronting words of William Lyon Phelps: “The Bible has been a greater influence on the course of English literature than all other forces put together.”

What does that mean?

Well, we’ll sprinkle a few choice phrases in this message as we go. For starters there’s

– a drop in the bucket

– a law unto themselves

– a leopard cannot change its spots

– at their wit’s end

See how it goes? On my part, it was a great delight upon returning to graduate school in 1989 after twenty years preaching and teaching heartily from this master text, to find that English professors and literary critics still largely shared these sentiments. My own reading and rereading of English and American literature brought the following brief remarks to mind. These were stimulated by the insights of M.H. Abrams’ Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature.

For starters, English-speaking writers seem haunted by the Bible. For Californians, the relatively straight-forward starting point is John Steinbeck’s biblical titles Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden. Even the pseudo-nihilist Hemingway steals from “Ecclesiastes” the title The Sun Also Rises. The Old Man and The Sea’s Christ-symbolism surprised many when it appeared in 1952 and cemented the writer’s Nobel Prize. Thomas Wolfe praised “Ecclesiastes” as “the greatest single piece of writing I have ever known…the noblest and most powerful expression of man’s life upon this earth.” Herman Melville (and this is no fish tale) opined: “The truest of all men was the man of Sorrows, and the truest of all books is Ecclesiastes.”

Even our scribes of High Seriousness echo Scripture. Is The Great Gatsby the Rich Fool of the Parable? Is there not something of King Saul in Macbeth, Job in King Lear and David the invincible Warrior King in Henry V?

Here are a few more snippets of King Jamesisms if this literary review is getting ponderous:

– seeing eye to eye

– heart’s desire

– holier than thou

– the fat of the land

– my cup runneth over

Not bad, eh? Talk about a book with staying power. The alert reader will find his or her own.

In discussing Shelley and Wordsworth, Abrams alluded to that English tradition of “radical Protestantism” in much of the Romantics. “The burden of what they had to say was that contemporary man can redeem himself and his world, and that his only way to this end is to reclaim and to bring to realization the great positives of the Western past.” 4 He went on to cite the chief of these values as life, love, liberty, hope and joy and that in all this the “ground-concept” is life, life itself as the highest good. Life is “the generator of the controlling categories of Romantic thought” adds Abrams. In all this, says Abrams, “the norm of life is joy.” Joy is that true sign that “an individual in the free exercise of all his faculties, is completely alive” and that what he refers to later as “the abundant life” is “the necessary condition for a full community of life and love.”

Here is the mainspring for much of the enduring art of the past two centuries, claims Abrams.

Really? How many know today that love, joy, peace are some of the very attributes set forth as “fruits of the Spirit” in Ephesians, Chapter Five.

Here’s our third and last list of Jamesisms:

– put your house in order

– the straight and narrow

– sign of the times

– sour grapes

– ends of the earth

– root of the matter

Yes, there’s no book like it or never will be again, especially as we move into a post-Christian post-Biblical age.

The modern translation that said “God never dozes” was trying to be helpful but would win no prize for grace and elegance over the KJV’s “shall neither slumber nor sleep” (Psalm 121: 4). Henry Van Dyke set forth this encomium, a tribute which colorfully compresses so much of why the Bible is considered both the Master Text and the Great Code:

“Born in the East and clothed in Oriental form and imagery, the Bible walks the ways of all the world with familiar feet and enters land after land to find its own everywhere. It has learned to speak in hundreds of languages to the heart of man. Children listen to its stories with wonder and delight (Jonah and the Great Fish), and wise men ponder them as parables of life (Jonah and Free Will). The wicked and the proud tremble at its warnings, but to the wounded and penitent it has a mother’s voice…No man is poor or desolate who has this treasure for its own.”

It seems ironic when people wonder if God is dead or has wandered off somewhere that a book such as Psalms – perhaps my favorite – lies pulsating with the turbulent ups and downs of life. Turn to any of the 150 little mini-excursions into life and all its joys and perils.

At your wit’s end? Try Psalm 11 and its opening cry – “Help, Lord!”

Surrounded by baddies? Try Psalm 3.

Mad at God himself? Open Psalm 10.

Need help driving? Psalm 121:4.

There’s a Psalm for every mood – I mean every mood – and after perusing them even very briefly we can never say again: ”If only God would say something.”

God is alive. He is near. He does care. He has spoken – often and clearly. The Psalms will convince you of that.

Most of our best writers and authors seem to have thought so. Perhaps it’s time to try it for yourself.

1 Peter Ackroyd, Albion: The Origins of the English Imagination (London: Chatto and Windus, 2002), page 301.

2 F.W. Faber from “Review of Reviews” quoted in Lawrence E. Nelson, Our Roving Bible: Tracking Its Influence Through English and American Life (New York/Nashville: Abingdon-Cokesbury Press, page 87.

3 Quoted in H.H. Halley’s Halley’s Bible Handbook (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1965 edition), page 18.

4 M.H. Abrams, Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature (New York: W.W. Norton and Comoany, 1971), page 430.