Atonement – A Journey Into God's Heart

By Neil Earle

Last month’s tenth anniversary commemorations of the horrors of September 11, 2011 were sincere and heartfelt. Our own church paid tribute to the victims and the scale of that awful day. Yet in the midst of our public mourning one could have sensed certain numbness, even a hollowness, perhaps, behind our well-orchestrated media responses, a response that seemed to indicate we still have not made sense of it all.

For Christians, the words of one of the leading theologians of our era can speak to us in this dilemma. “Humanity is engulfed in an abyss of fearful darkness too deep for men and women themselves to understand,” wrote Scottish pastor Thomas Torrance. “It is certainly too deep for them ever to get out of it.”

This is strong language. Yet when we realize that crazy people have the ability to fly planes into sky-scrapers and kill thousands in the process because of something that could be traced back to the Middle Ages…well, we somehow sense that a wound has been exposed at the heart of our human civilization, a blindfold torn from our eyes forcing us to see things we’d rather not look at. When we also consider that violence tends to beget more violence – that Pearl Harbor led to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, for example – we might agree with Torrance’s diagnosis: “Mankind is entangled in sin not (always) of its own making, enmeshed in the toils of a vast evil quite beyond it.”

Of Goats and Priests

The Jewish high holy day of Yom Kippur means “Day of Covering.” The word “kippur” or covering refers to the blood of a bull the High Priest applied to cover the mercy seat in the tabernacle. This sacrifice made atonement for the people of Israel (Leviticus 16:14).

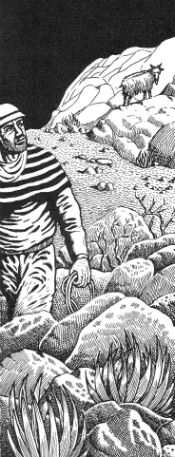

The goat symbolizes the despised Messiah as the lamb is the innocent Messiah. (Artwork by Basil Wolverton)

Christians believe that this sprinkling symbolized Christ’s blood shed for us making Jesus the “propitiation” or “sacrifice of atonement” for all our sins (Romans 3:25). The word “propitiation” (see the KJV) is “hilasterion” in Greek and it means mercy seat.” It refers right back to that Old Testament symbolism. Blood became symbolic of how our reconciliation with God was made.

Also on Yom Kippur the priest sacrificed two goats (Leviticus 16:6-10). One was offered on the altar and the other led away into the wilderness (the escaped goat or “scapegoat”). For years our church – then named Worldwide Church of God – taught that the scapegoat symbolized Satan the Devil. The Aaronic priest laid on this goat all the sins and iniquities of the children of Israel before its banishment (Leviticus 16:21).

It now seems more logical to accept the simple truth taught in such companion texts as Isaiah 53:6 (“the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all,” i.e. Christ). See also John 1:29, Micah 7:18-19 and especially Psalm 103:12 where God has “removed our sins far from us, as far as the east from the west.” Think now how Satan cannot be the sin bearer for Israel or anyone else – only Jesus can make that atonement.

Nevertheless the early church built on those Old Testament pictures of sacrifice when Jesus’ death was discussed. As J.I. Packer summarizes: “The Cross propitiated God (i.e. quenched his wrath against us by expiating our sins and so removing them from his sight” – Romans 3:25, Hebrews 2:17, 1 Peter 1:13-1). The removal of sin is God’s business alone and nothing to be ascribed to our arch-foe, the Devil (Hebrews 10:10).

Around 320 AD Saint Athanasius beautifully summarized much atonement teaching by stating: “The Atonement is not simply something God does, it is who God is in the Incarnation” (Jinkins, Invitation to Theology, page 140).

While the Middle Ages stressed Satisfaction as the motive in the Atonement (see article), and the Protestant Reformers stressed Jesus as our Substitution, much 20th Century theology turned back to Athanasius’ idea that Atonement is inherent inside the heart of the Trinity.

This is the teaching that Jesus emptied himself of his divinity (Philippians 2:7-8) to become a man who could die as well as God and thus reconcile us back to God. This stress puts emphasis on the reconciliation motive undergirding Atonement: God purposes to bring many sons to glory (Hebrews 2:7), an inclusive teaching more deeply centered on the Love of God and his all-embracing nature.

As Torrance well knew, disentangling suffering humans from that vast evil was part of the Mission Statement of Jesus Christ of Nazareth whose incarnation as both God and man touches very directly on that mysterious process the Bible calls “atonement.” Today, October 8, on the Jewish Day of Atonement or Yom Kippur, makes a good time to think of all this.

Making Satisfaction

Atonement has been called “a problem fit for God,” and a “dark mystery.” Yet every parent and every jury has to deal with some of the basic elements behind atonement – How to remit punishment without cheapening sin? How do you pardon a wrong while maintaining the right? How to restore the guilty and yet teach the offender to hate his offense (Grensted, The Atonement in History and Life, page 233).

As human beings we know we fail and come short of the great moral law of God. Then we read that God hates sin (Jeremiah 44:4) and moves to punish it (Romans 1:18). But how do we find our way back? How is reconciliation with the offended deity effected?

One of the problems in answering this is inherent in the meaning of the English word “atonement” itself. It has come to mean, says J.I.Packer, “making amends, blotting out misdeeds, making satisfaction for wrongs done” (Concise Theology, page --). Okay. That is an adequate definition as long as we realize that the making amends and making satisfaction for sin is not something we can do for ourselves, yet alone disentangling ourselves from “the vast evil all about us.” The term “at-one” subtly implies an equality between us and God that is not there. Satisfaction for sin must come from the divine side of the equation. Deep down, we all know this.

A Hindu man came to Gandhi. He said, “I am in hell. I killed Muslims in the recent war.” Gandhi says, “I know a way out of hell. Take your favorite child, raise him as a Muslim, embrace him as a Muslim, and love him as a Muslim. This is the way out.”

That is a succinct way to see atonement in action – we feel we have to “do something” to make amends. Of course what Gandhi said is wise and works on the human scale even if it works best in a one-on-one situation. But when we consider Torrance’s “abyss of fearful darkness…a vast evil” such as leapt out at us in 9/11 we realize we can never as one individual atone for such things as the Jew-Palestinian hostility, the India-Pakistan conflicts, the Iranian-American tension or even the Christian-Atheist divide which seems to get wider all the time.

No. One man is helpless to do anything about this, to turn the great big human mess around, unless...unless that one person were worth more than the whole human race put together. In that case we might have a chance, a hope perhaps that some of these grievous divisions could be reconciled. A Medieval theologian named Anselm of Canterbury (died 1099) wrestled with this very idea of atonement in a treatise he called “Why the God-Man”? Anselm wrote of Jesus Christ who became sin for us, who took the curse of all human hatred and bitterness, drew it into himself and paid the debt we all owed. “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the Law by becoming a curse for us” (Galatians 3:13).

Thomas Torrance puts this in his own eloquent way in his Incarnation: The Person and Life of Christ (me roughly paraphrasing):

“The Son of God who was also Son of Man came among us, as the Nicene Creed says, “for us men and for our salvation.’

“This is what God did. He took the initiative. He came among us as the Strong Man of his own parable who invades the tyrant’s house and by his mighty power subdues him, binds him and spoils him of all that he unjustly usurped (Luke 11:23).

“But Jesus subdues evil not by divine violence, not by calling down twelve legions of angels, but by obedience and steadfastness and submission as the Son to the Father in the face of the contradiction of sinners and the attack of every power that evil could throw against him.”

The Bitter Price

Torrance focuses here on the depth of the sacrifice Christ made and sacrifice has always been close to the heart of Atonement (Leviticus 1:4). That’s one reason the Australian bishop Leon Morris argues that the way Jesus died on the cross is almost as important as the why. Jesus did not die of a painless injection in the electric chair but brutally, violently, torn apart and pierced by a merciless scourging that perhaps only one in ten survived. The climax was the aggressive thrust of a Roman lance so fatal as to open his side so that blood and water flowed out (John 19:34).

That is important to remember – the bitterness of the cross. Someone had to pay and Jesus voluntarily became sin for us. As Torrance says: “By patience and faithfulness and godliness and always motivated by love above all, Jesus advanced to meet his death, he drew evil unto himself and annulled it at the very moment of evil’s greatest power.” This is why Saint Paul makes that mysterious and mystical statement that when Jesus died we all died with him, the whole creation (2 Corinthians 5:14). At the cross, something cosmic occurred, says Paul, so that the law could be satisfied.

This is a profound point but it is perhaps mirrored in those three hours of darkness Jesus spent on the cross drinking the full cup of our iniquity.

The Twofold Deliverance

Some medieval theologians were so inspired by this total acceptance of suffering on Jesus’ part that they taught the Ransom Theory of atonement. That the devil was deceived into engineering Jesus’ death not knowing he was being duped by inflicting such a painful death on the Son of God and yet by doing this he inadvertently helped secure our salvation. We don’t have to believe that to make the point – it is just good to note how the majesty and awesomeness of the Atonement has attracted numerous thinkers across the ages.

But these older thinkers were getting at what we often forget – the painful cost involved in Jesus’ death, a death so awful that Jesus can face the victims of 9/11 and their loved ones with a clear conscience. The spectacle of the Crucified God was so horrible that God the Father could say, “All debts are paid! Come home to me, my lost children. I am not mad at you.” Again, this reminds us of the Prodigal’s father in Jesus’ own parable.

The ransom price was paid: Jesus won the human race back to the perfect relationship the Father and the Son had enjoyed through all eternity. As Jesus prayed in his last High Priestly prayer: “Father I want those you have given me to be with me where I am and to see my glory, the glory you have given me because you loved me before the foundation of the world” (John 17: 24).

Now that is reconciliation and the atonement that precedes it in full flow! “The debt has been paid. I do not hold your sins against you any more and I am moving to defeat and nullify the evil in this world, and all because the Beloved Son has won the human race back to me by his death through the power of the eternal Spirit that was in him (Hebrews 9:14). Jesus won by losing. By dying he defeated death and sin. He was the true Mediator between God and man (1 Timothy 2:5).

This is why Paul says the blood of bulls and goats cannot take away sin but the blood of this man can, because this man was God in the flesh, in whom dwelt the fullness of the deity (Colossians 2:9).

This is why Christians teach, says Torrance, that the purpose of Atonement is to reconcile humanity back to God – first the elect, and then everyone at the end (Revelation 20:12). Satisfaction has been made and it all rests upon the love of God – the love of the Son in taking all our evil into himself. Love has triumphed against Law, the very Love of the Father in accepting us along with the Son into the heavenly realms (Ephesians 2:1-7).

In that sense the Atonement on the cross covers what Torrance calls both the negative righteousness of Jesus dying for us in the painful expiation of our sins AND the positive righteousness of the Son’s obedient life that makes us accepted in the Beloved (Ephesians 1:6).

Jesus did not die to change the mind of an angry God but to incorporate us into an inclusive relationship with the Father and Son through the communicating power of the Holy Spirit (2 Corinthians 14:12). That knowledge has reached you. Atonement and reconciliation with God are just a prayer away, right now, today. Thanks God for his atoning grace.